People Love “What If” Moments. Are We Living Through One Now?

Counterfactuals endure as the odd man of historiography. Audiences are fascinated by the Amazon adaptation of the Philip K. Dick science fiction classic The Man in the High Castle and readers ponder alternate history as imagined by Philip Roth in The Plot Against America, but academic historians are circumspect about the question of “What if?” The rest of us, however, can’t resist contemplating alternate history – what if Napoleon had been victorious at Waterloo? If Hitler had only been accepted into the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna? History as practiced in the subjunctive must by necessity be a subjective science, which is perhaps why it’s so often left to novelists rather than scholars.

Nevertheless, historian Martin Bunzl, advocating for the usefulness of counterfactuals, notes that they’re “not as easy to avoid in the practice of history as one might think.” Any interpretation of why an event happened holds within it the implicit possibility that it could have happened differently. Helpful to remember in the midst of history, where the currents of what might happen seem to shift with every push notification. The question of “What if?” dwells within the domain of imagination, serving to keep us honest, disavowing us of that teleological fallacy that interprets providential certainty into events. Counterfactuals, in literalizing the possibility that things could have turned out differently, underscore that anyone who claims to know how our current drama will end is deluded.

If epochs are defined by “hinge years” to which the counterfactual historian is naturally drawn – 1776, 1787, 1860, 1933, 1945 – than perhaps we’re living in one ourselves, when as Marx would say “all that is solid melts into air.” Certainly it feels that way now, as Donald Trump runs roughshod over the Constitution, as authoritarian tendencies are enflamed, and just this week as Americans watched the sickening spectacle of Bret Kavanaugh’s testimony. Kavanaugh, of whom there is compelling evidence that he may be a serial sexual assaulter, denounced investigation into his conduct with the most partisan language imaginable, all in the service of his appointment to a Supreme Court seat which he acts as if he’s entitled to, and which congressional Republicans are intent on even after they denied Merrick Garland his hearing.

Easy to assume that we’re presently witnessing the rapid dissolution of both FDR’s New Deal and the hard-won victories for women’s rights, civil rights, LGBT rights and so on, which were acknowledged over the past decades. Something seems inevitable about this reactionary march, as a corrupt kakistocracy defined by men like Trump and Kavanaugh – the very dregs of mediocrity – ensconce themselves in the nation’s capital. Easier still to become dispirited at the spittle-flecked raging of Kavanaugh, who despite possibly having perjured himself during his confirmation hearings still has the support of Senate Republicans, and who simply see a position on the Supreme Court as one more thing that he deserves, and not the sacred trust that he’d be honored with in service to his fellow citizens.

Counterfactuals implore us to never forget the contingencies of history, to avoid both the positive teleology, which assumes that progress is always guaranteed, as well as the equally pernicious teleology that prefers to wallow in the excesses of despair. That history is not written yet may be a cliché, but like all great clichés it has the invariable attraction of also being true. For if ours is a moment that seems defined by these specters of corruption and fascism, then there has also been a mighty upswell of opposition to Trumpism, one which sees an explosion of women’s involvement in Democratic politics, a reinvigoration of the labor movement across the American heartland, and the rise of legitimate Democratic Socialist possibilities.

The mass media have been largely slow to report on the commitment and diligence of women and men who protest the Trump regime, and who are constructing spaces of opposition often in what coastal pundits might consider the most unlikely of places. Simply put, if you despair at Trump (and you should), just know that the single biggest underreported story is the massive movement against him, which is arguably composed of more participants than the protests against the Vietnam War, and which has already born out electoral victories. Sarah Kendzior, one of the most talented journalists covering this particular issue today, writes in the Globe and Mail that far from the snarky jokes about “The #Resistance,” the opposition against Trump is composed of “simply millions of Americans who know they deserve better. It is less a resistance than an insistence that privileged impunity will no longer stand.” History, remember, is not yet written.

Which is precisely the current dialectic that we see being played out in these confirmation hearings. Too often Trump’s malice is interpreted as mere incompetence, where the improper vetting of such a compromised candidate as Kavanaugh and the subsequent digging in of heels to support him is seen as bush-league immaturity. If only that were the case. Kavanaugh is in part the nominee precisely because of his privileged immorality. Defending his nominee at the anarchic, tossed word-salad of a press conference on September 26th, Trump stated that the accusations against Kavanaugh simply stiffened his resolve, explaining: “Does it affect me, in terms of my thinking, absolutely.” Trump sees Kavanaugh as a kindred spirt, which is part of why he and Senate Republicans are so adamant about appointing the jurist when there are dozens of other qualified Federalist Society vetted right-wing judges who’d please the reactionary GOP. Indulging my own counterfactual, if Trump had nominated the Notre Dame law professor (and theocratic extremist) Amy Coney Barrett, she’d be sitting on the Supreme Court right now.

Kavanaugh’s appeal to Trump is precisely that he represents a response to the increasing rights of women and minorities who the contemporary Republican Party defines itself in opposition to. Kavanaugh is literally the anti-#MeToo nominee. In his brilliant essay “The First White President,” former Atlantic essayist Ta-Nehisi Coates argued that the “foundation of Donald Trump’s presidency is the negation of Barack Obama’s legacy,” and by proxy the legacy of progress which civil rights generally represent. By puckishly arguing that Trump is the “first white president,” Coates claims that the failed businessman and former gameshow host is the first president elected explicitly because he is white, and for his supporters, his boorishness and banality is a feature and not a bug of his personality. I’d argue that something very similar is true for Kavanaugh, that Trump’s support for his nominee is in imagining him as the “first male justice,” a symbol of entitlement who would serve on the highest court not in spite of the assault he potentially committed, but in part because of it.

This is how the dialectic between radicalism and revanchism always operates, for conservatism is defined not as an ideology, but rather as a counter-revolutionary phenomenon which exists to preserve power on behalf of those who hold it and who fear that it’s being taken away from them. Political theorist Corey Robin argues in The Reactionary Mind: Conservatism from Edmund Burke to Donald Trump that since the French Revolution, conservatism should be understood as a “broad-based movement of elites and masses against the emancipation of the lower orders.” In her debut New York Times piece last week, Michelle Alexander substantiated Robin’s argument about what conservatism actually is, noting that “Donald Trump is the one who is pushing back against the new nation that’s struggling to be born.” We are not the resistance – what is being resisted is us.

Read from such a perspective, the Kavanaugh appointment makes more sense. Kavanaugh would symbolize the victory of patriarchalism; his role is to signify that for the right, rules do not apply equally across our society. Kavanaugh’s anti-emancipatory bona fides are all the more disturbing when you look at the Supreme Court docket for October, and see that the justices will be ruling on Gamble vs. No 17-646, where he would be the deciding opinion that would eliminate the “separate sovereigns” exception for double-jeopardy, which would then allow Trump to pardon all of his past and potentially future convicted criminal associates without fear that state charges could be brought against them.

We are effectively in the midst of an ideological cold civil war, where the right is organized, ruthless, and committed to the complete destruction of an expansive America that franchises the rights of all of its citizens. Novelist Steve Ericson in an interview with The Believer makes the argument that it’s time for liberals to fully grapple with that score, saying that the “Right drew a line long ago and has regarded the rest of us as the enemy ever since, and we’re only now realizing they were correct all along. We are the enemy, and it’s probably time to stop doing that old progressive thing of, you know, trying to get along.”

Which is what has hobbled the mainstream of the Democratic Party and their unctuous centrists for generations now. We’re often told that as we live under an increasingly authoritarian administration that we should continually remind ourselves that “This is not normal,” but that’s an anemic challenge, valorizing normalcy at the expense of morality. Of course, it wasn’t normal that Mitch McConnell wouldn’t even give Garland a hearing, of course it isn’t normal that Kavanaugh would be pushed through without proper vetting. None of these things are normal, what’s important is that they’re also wrong.

In the long list of his sins, Trump’s lack of normalcy is fairly low down. Rather, what’s horrific is his abject malignancy as a human being and his role as an avatar for all of those chthonic forces within our culture. Normalcy is not synonymous with good. It’s also not normal that a 27-year-old Democratic Socialist defeated an entrenched Democratic machine politician, but it’s also good. It wouldn’t be normal for a sitting president to be indicted, convicted, and sentenced, but it’s good right now.I’ll also add that it wouldn’t be normal for a future Democratic majority to pack the Supreme Court and fast-track Washington DC and Puerto Rico statehood, as suggested by David Faris in It’s Time to Fight Dirty: How Democrats Can Build a Lasting Majority in American Politics, but it would also be necessary, welcome, and overdue. Ruthlessness in the defense of justice is no vice, and inefficacy in the defense of normalcy is no virtue.

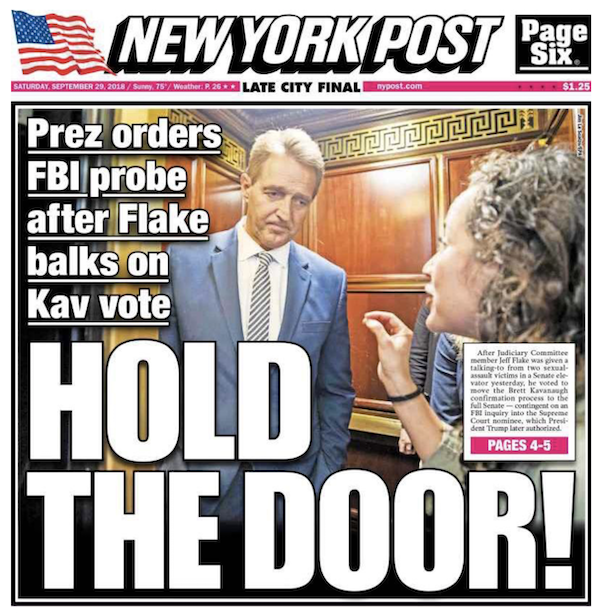

Such are the vagaries of the hinge year, when our fate must be frustratingly occluded. I’ve no idea if Kavanaugh will be confirmed or not, and nobody else does either. History is too fickle. Perhaps we’ll be fortunate enough that a half-century hence historians will write about how the brave actions of sexual assault survivors Ana Maria Arcila and Maria Gallagher, when they confronted Senator Jeff Flake over his support of Kavanaugh, may have ultimately doomed the judge’s nomination. We’ll know in a few days. I also don’t know if the totalitarianisms of Trump signal an irreparable eclipse of American democracy, or if the hopeful indications in the election of DSA members to Congress (many of them women of color), the teacher’s strike in West Virginia, and the reinvigorated labor movement in Missouri bode for an emancipatory future. Right now, it’s too hard to tell; it’s too dark to see if the tide is coming in, or if it’s going out.