“Mr. Straight Arrow,” John Hersey, and the decision to drop the atomic bomb

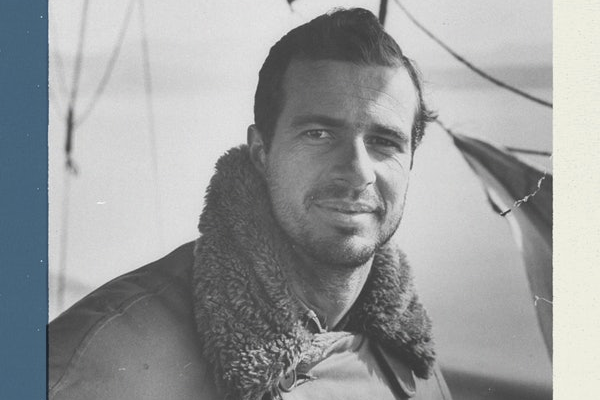

John Hersey

Roy Scranton’s ”How John Hersey Bore Witness” (The New Republic, July-August 2019) is an insightful look at a new book on one of my favorite authors. It touched all the right notes and has prompted me to add Mr. Straight Arrow to my “Christmas list.” Sadly, in the midst of this otherwise fine review, author Scranton repeats the discredited old chestnut that President Harry S. Truman dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki even though he knew Japan was trying to surrender. Truman’s real reason for using the weapons, according to Scranton, was to employ them as a diplomatic club against the Soviet Union. This allegation was popular in some quarters during the 1960s and 70s, but was only sustained by a systematic falsifying of the historical record and it continues to pop up even today.

Underscoring this sad fact is the link Scranton provides which takes readers to a 31-year-old letter to the New York Times from Truman critic Gar Alperovitz purporting that “dropping the atomic bomb was seen by analysts at the time as militarily unnecessary.” Presented in the letter is an interesting collection of cherry-picked quotes from a variety of diary entries and memos by contemporaries of Truman, such as Dwight D. Eisenhower. All are outtakes and have been long rebutted or presented in their actual contexts. Even key figures are misidentified. For example, FDR’s White House chief of staff Admiral William D. Leahy, who chaired the meetings of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, is elevated in the letter to the position of Chairman of the Joint Chiefs.

As for the notion that Japan was trying to surrender, this is not what was beheld by America’s leaders who were reading the secretly decrypted internal communications of their counterparts in Japan.

In the summer of 1945, Emperor Hirohito requested that the Soviets accept a special envoy to discuss ways in which the war might be “quickly terminated.” But far from a coherent plea to the Soviets to help negotiate a surrender, the proposals were hopelessly vague and recognized by both Washington and Moscow as no more than a stalling tactic ahead of the Potsdam Conference to prevent Soviet military intervention --- an intervention that Japanese leaders had known was inevitable ever since the Soviets’ recent cancellation of their Neutrality Pact with Japan.

Japan was not trying to surrender. Even after the obliteration of two cities by nuclear weapons and the Soviet declaration of war the militarists in firm control of the Imperial government refused to admit defeat until their emperor finally forced the issue. They had argued that the United States would still have to launch a ground invasion and that the subsequent carnage would force the Americans to sue for peace leaving of much of Asia firmly under Japanese control.

The war had started long before Pearl Harbor with the Japanese invasion of China, and millions had already perished. That Asians in the giant arc from Indonesia through China --- far from Western eyes --- were dying by the hundreds of thousands each and every month that the war continued has been of zero interest to Eurocentric writers and historians be they critics or supporters of Truman’s decision. As for the president, himself, Truman rightfully hoped, after the bloodbaths on Okinawa and Iwo Jima, that atomic bombs might force Japan’s surrender and forestall the projected two-phase invasion which would result in “an Okinawa from one end of Japan to the other.”

Hersey understood this well. Fluent in Chinese (he was born and raised in China), Hersey was painfully aware of the almost unimaginable cost of the war long before the United States became involved and, after it did, observed the savagery of battle on Guadalcanal first hand. Yes, he understood it quite well and it will come as a surprise, even shock, to many that neither Hersey nor Truman saw Hiroshima as an indictment of the decision to use the bomb.

Those were very different times and the prevailing attitude, according to George M. Elsey, was “look what Japanese militarism and aggression hath wrought!” (Truman also made similar observations when touring the rubble of Berlin during the Potadam Conference.) The president considered Hiroshima an “important” work and, far from being persona non grata, Hersey would sometimes spend days at a time in Truman’s company when preparing articles for The New Yorker. This level of access was not accorded to other journalists and circumstances resulted in Hersey sitting in on key events such as when Truman learned that the Chinese had just entered the Korean War and a secret meeting with Senate leaders over the depredations of Joe McCarthy.

Although exceptions can be found in the literature, Hersey’s Hiroshima was simply not viewed in the postwar period as an anti-nuclear polemic and Elsey, who served in both the Roosevelt and Truman administrations before going on to head the American Red Cross for more than a decade, remarked to David McCullough that “It’s all well and good to come along later and say the bomb was a horrible thing. The whole goddamn war was a horrible thing.”

Scranton, himself, gives a brief nod to this fact, admitting that the midnight conventional firebombing of Tokyo earlier that year killed even more people, approximately 100,000, yet one shudders to think what he teaches to his unsuspecting students. The “revisionist” Japanese-were-trying-to-surrender hoax prominently recited in his review of Mr. Straight Arrow has long been consigned to the garbage heap of history by a host of scholarly books and articles* including, ironically, a brilliant work by one of Scranton’s own colleagues at Notre Dame.

Father Wilson D. Miscamble’s The Most Controversial Decision: Truman, the Atomic Bombs, and The Defeat of Japan (Cambridge University Press, 2011) is a hard hitting, well researched effort that is especially notable for its thoughtful exploration of the moral issues involved. Though Scranton and Miscamble share the same campus, a colleague of mine maintains that the two scholars have never met. Perhaps they should get together for coffee some morning.

--------------------------

* Six particularly useful works are: Sadao Asada’s award winning, “The Shock of the Atomic Bomb and Japan’s Decision to Surrender -- A Reconsideration,” Pacific Historical Review, 67 (November 1998); Michael Kort, The Columbia Guide to Hiroshima and the Bomb, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007) and “The Historiography of Hiroshima: The Rise and Fall of Revisionism,” The New England Journal of History, 64 (Fall 2007); Wilson D. Miscamble C.S.C., The Most Controversial Decision: Truman, the Atomic Bombs, and the Defeat of Japan (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011); Robert James Maddox, ed., Hiroshima in History: The Myths of Revisionism, (Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 2007); Robert P. Newman, Enola Gay and the Court of History, (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2004).