What Does History Tell Us About Impeachment and Presidential Scandal? Here's 7 Historians' Analysis.

What a week! I--like many of you, I’m sure—have been glued to my phone, constantly hitting refresh on Twitter and the Washington Post’s website.

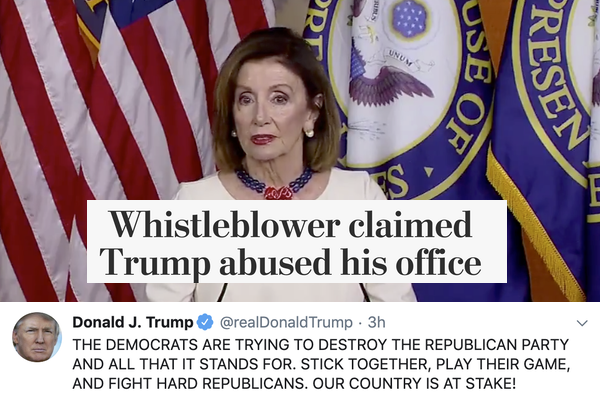

This morning alone, lawmakers released the whistleblower report at the center of the ongoing controversy over a phone call between President Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. Joseph Maguire, the acting intelligence chief, is testifying before the House Intelligence Committee. Trump’s response? “THE DEMOCRATS ARE TRYING TO DESTROY THE REPUBLICAN PARTY AND ALL THAT IT STANDS FOR. STICK TOGETHER, PLAY THEIR GAME, AND FIGHT HARD REPUBLICANS. OUR COUNTRY IS AT STAKE!”

Perhaps most significantly, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi announced she would launch a formal impeachment inquiry on Tuesday. 218 members of congress now support an impeachment inquiry—a majority of the 435 members of the House of Representatives.

As we wait for the next big development to break, it’s valuable to pause and zoom out to the bigger picture of American history. To help us to do that, students in my “History and the News” class asked several historians to offer their perspective on this week’s events. Some are established historians; some are in graduate school. All provide valuable insights into the historical context of this momentous week.

“I expect a tumultuous next year”

Eladio B. Bobadilla (@e_b_bobadilla), Assistant Professorat the University of Kentucky

Historically, impeachment has been exceedingly rare. Only two presidents have been impeached—Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton—and neither was convicted.

The two cases were starkly different. In the backdrop of Johnson’s impeachment lay critical debates about Reconstruction, a defining period for millions of newly-free African Americans and their descendants. The case of Clinton, by contrast, revolved around allegations of personal (specifically, sexual) misconduct. What the two did have in common—beyond the failure of the Senate to convict—narrowly in the case of Johnson, less so in the case of Clinton—was that they proved to be captivating political theater and that they reflected deep divisions in both government and the population.

While historians are hardly equipped to predict the future, I expect a tumultuous next year, especially as we head to an election season that will be defined by impeachment proceedings and political, legal, and social battles.

Impeachment has historically “made it difficult for the president to keep control of the public conversation”

Varsha Venkat (@varsha_venkat_), PhD student at the University of California, Berkley

An impeachment inquiry is more than just an indictment against the president’s actions, historically it has made it difficult for the president to keep control of the public conversation. In our current technological age with the 24 second news cycle, this is probably the most important consequence of the House’s decision to begin an impeachment inquiry. Johnson, Nixon, and Clinton each experienced this loss of control as well. It has also been the case that historically, during the turmoil of an impeachment process, the president has been more receptive towards compromise and even restraint. Though President Trump has not revealed this capacity during his time as president so far, one can hope that even the process of daily hearings and public discussion about his removal will lead him to reconsider some of his more problematic decisions. History shows us that impeachment has been a political decision, and it is important to keep in mind the political consequences for both the Democratic and Republican parties during this process, not just the potential consequences for the president.

“The rule of law is legitimately threatened at this moment”

Jennifer Mercieca (@jenmercieca), Associate Professor at Texas A&M University

The rule of law is threatened by right wing nationalists all over the world. Yesterday we saw institutions in two nations make political decisions to uphold the rule of law. Most people watching the events unfold yesterday in Britain and the US probably didn't notice that both the UK Supreme Court and the US House of Representatives justified their decisions based upon the need to defend the rule of law. That's historic both because the rule of law is legitimately threatened at this moment and because institutions are acting to defend it. I hope, we all hope, that this isn't the moment that future historians will point to as the rule of law's "last stand."

Impeachment “comes with political and historical red flags”

Andrew Hartman (@HartmanAndrew), Professor of History at Illinois State University

Getting impeached would be just desserts for Trump, someone who has always skirted legal boundaries for selfish purposes, a habit that did not end when he became president (in fact got worse because the stakes became much higher). But I would qualify this in two ways: 1) There's a great deal of uncertainty as to whether this will work to the benefit of Democrats, since it will embolden Trump's sense of victimhood which he has played to his advantage for the last four years. Some would argue that political calculation should not factor into impeachment considerations because the law's the law, but this is naive since politics always and especially factors into something as serious as impeachment. Moreover if people are that concerned with law and order in the White House there are hardly any presidents that have not deserved impeachment, which leads me to my second qualification. 2) What does it say when our willingness to impeach is correlated to the potential political advantage and not to matters of war. Nixon should have been impeached for illegally bombing Cambodia, a much more serious offense than Watergate. Reagan should have been impeached for the CIA illegally mining Nicaraguan harbors under his watch. The list goes on and is not limited to Republican presidents. The immoral and unjustifiable Vietnam War was ultimately a Democratic war for which LBJ deserved impeachment or worse. In short, impeaching Trump would feel good to those of us who find him a disaster of a human being and an embarrassment to the nation. But it comes with political and historical red flags.

P.S. I wrote the above before the whistleblower complaint was made public. It seems more likely than ever that Trump might finally be in trouble. The dam seems to have finally broken. Which is good, and perhaps changes the political calculation (though not the historical calculation).

“The law is whatever those in power make it”

Derek Litvak (@TheTattooedGrad), PhD student at the University of Maryland

“No one is above the law.” When Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi said this, a question I often ask myself came to mind. What is the law? Studying legal and constitutional history has brought me to the same conclusion on many occasions: The law is whatever those in power make it. And therefore, the Constitution, as the “supreme law of the land,” follows suit. However, as much as history has taught me this lesson, it has also shown me how much those not in power can affect change. From the abolition of slavery, to women’s rights, to marriage equality, the law and our Constitution have always been a battleground. Some battles are won. Many are lost. I remain hesitant to put much stock in Speaker Pelosi’s “impeachment inquiry,” as opposed to formal articles of impeachment. But perhaps Democrats are now willing to at least fight the fight, and stop letting those in power make the law what they wish.

“The sustained grassroots pressure…seems to have finally born fruit”

David Walsh (@DavidAstinWalsh), PhD Candidate at Princeton University

To me, one of the biggest questions for historians when thinking about the impeachment saga is, "why now?" After all, Trump committed essentially the same set of offenses during the 2016 election and actively obstructed justice in office while attempting to cover it up -- which ultimately culminated in what essentially amounted to an impeachment referral by Special Counsel Robert Mueller to a Democratic House less than six months ago. And the Democrats punted. So what changed? There are two factors: one, this is an *active* attempt to solicit foreign aid by the sitting president for his ongoing re-election bid. The smoking gun, as it were, is still in the president's hand. That makes this scandal distinctive from Watergate, Iran-Contra, and even Trump's criminal behavior in 2016. Two, the fact that congressional Democrats punted on impeachment six months ago has fueled a tremendous amount of anger at the party from its voting base. The sustained grassroots pressure on Democratic incumbents to, in the words of Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib, to "impeach the motherfucker," seems to have finally born fruit.

Trumps’ behavior is “exactly what the Founding Fathers worried” about

Rick Shenkman (@rickshenkman), founder and former editor-in-chief of the History News Network

Republicans are, it is safe to assume, going to disparage Speaker Pelosi’s decision to begin a formal impeachment inquiry. But given what we know already about President Trump’s behavior an impeachment inquiry is exactly what the Constitution calls for. At the heart of the latest Trump violation of historical norms is the allegation that he turned to a foreign government for dirt on potentially the strongest opponent he is likely to face in the upcoming 2020 election, according to current polls. This goes Richard Nixon one better. To take out his perceived strongest opponent (Ed Muskie) in the election of 1972 Nixon merely resorted to a series of dirty tricks. Trump, in contrast, has shown a willingness to involve a foreign government in his machinations. This is exactly what the Founding Fathers worried might happen and is the reason they went to such great lengths to insulate the presidency from foreign influence. There is a reason the Founders included in the Constitution the clause forbidding a foreign government from bestowing on any federal officeholder "any present, Emolument, Office, or Title, of any kind whatever” without the approval of Congress. They worried deeply that our politics could be upended by foreign meddlers, as in fact happened almost immediately when French Citizen Genet saw fit to involve himself in our affairs in George Washington’s second term. The present case is a kind of reverse Genet Affair. All accounts suggest in this situation the foreign power in question has wanted nothing to do with this nasty business. Rather, it is the president of the United States who instigated it. That surely compounds the crime.