A Senate Impeachment Trial Isn't Really a Trial and It Was Never Meant to Be

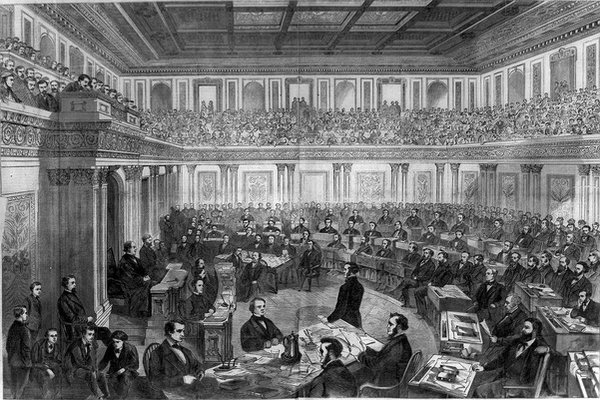

Depiction of the impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson in 1868

Can a trial be called a trial if…

- …as many as one hundred men and women who share the same workplace sit on the jury--after openly discussing the case with each other, the public, and the press?

- If some jurors are close friends or bitter foes--of each other and the defendant?

- If the defendant has helped some jurors obtain jobs?

- If the defendant appointed the judge to the bench?

- If the judge cannot rule from the bench or control the course of the trial?

- If conviction requires only a two-thirds majority of jurors?

- If the only penalty is unenforceable removal of the defendant from his job?

Obviously not!

Nor was it meant to be.

The proceeding described above was designed for one and only one person: the President of the United States of America, and it was not meant to punish but to deter further wrongdoing. It was the Constitutional Convention’s attempt to solve an insoluble dilemma: how to give one or two governmental branches the power to prevent wrongdoing by a third branch in a government of three separate-but-equal branches. The very question was a contradiction in terms, and the Founders knew it. They realized that only those who elected the President should have power to remove him—presumably by voting him out of office at the end of his four-year term. But they sought a more immediate remedy in case the President’s actions presented a present danger.

At a time when only about 30,000 white, adult, male property owners could vote, the Founders sought a compromise solution to the separate-but-equal dilemma by letting the “people’s house” charge the president with misbehavior—“impeachment”--and have the Senate “try” but not punish him. The trial and threat of removal would serve only to “check” his alleged abuse of power during the remainder of his term.

Only two American presidents have suffered such trials: the 17th president, Andrew Johnson, in 1868, and the 42nd president, William Jefferson Clinton, in 1999-2000. As the Founders had planned, both suffered humiliation but neither was convicted.

President Johnson, a Tennessee Democrat who had opposed secession, had run for vice president on a unity ticket with Republican Abraham Lincoln and assumed the presidency after Lincoln’s assassination. He incensed congressional Republicans from the North by granting a general amnesty to former Confederate military and government officials. The Republicans retaliated by impeaching Johnson, but they lacked the two-thirds Senate majority needed to convict, and he finished his term.

President Clinton, a Democrat, lied under oath about his sexual relations with a White House intern, then obstructed justice by trying to influence a witness to lie on his behalf. The Republican majority in the House of Representatives expressed outrage and impeached him, but failed to muster the two-thirds vote for conviction and he, too, finished his term.

With Republican President Donald J. Trump facing what may be a similar fate, he and his Republican allies are complaining angrily about what they charge is a politically motivated procedure. Ironically, many--indeed most--delegates at the 1787 Constitutional Convention would agree—which is why they made conviction all but impossible and the penalty for conviction all but negligible.

With one-third of the Senate facing re-election every two years, they reasoned, enough senators who won election with the President in the previous election would link with senators facing re-election with the President two years hence to form a large enough bloc to prevent his removal.

Virginia plantation owner James Madison objected to any and all sanctions, arguing that threats of a Senate trial would leave the President serving “at the pleasure of the Senate” and violate the principle of separate but equal branches of government. South Carolina’s Charles Pinckney agreed: “If he [the president] opposes a favorite law, the two houses will combine against him and, under the influence of heat and faction, throw him out of office.”

But Hugh Williamson, a Scottish-born physician from North Carolina disagreed. “I think there is more danger of too much lenity than too much rigor towards the President.” To mollify Williamson, Madison proposed “Supreme Court trial of impeachments,” but drew only protests.

“The Supreme Court is improper to try the President,” Roger Sherman, a Connecticut lawyer, argued, “because the judges would be appointed by him.” Other delegates agreed, but realized they had reached a stalemate. In the end, they patched together a vague compromise that satisfied no one, provided no remedy for reining a malfeasant president, and bequeathed the dilemma to future Congresses.

Article I, Section 3, Para. 6: The Senate shall have the sole power to try all impeachments. When sitting for that purpose, they shall be on oath or affirmation. When the President of the United States is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside: and no person shall be convicted without the concurrence of two-thirds of the members present.

Article I, Section 3, Para. 7: Judgment in cases of impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any office of honor, trust or profit under the United States; but the party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to indictment, trial, judgment and punishment according to law.

As in the two previous presidential trials, the Senate will declare Mr. Trump not-guilty if, indeed, he goes to trial. The Constitution does not make trial mandatory, however. The Senate can—and may well—ignore the impeachments and not charge Mr. Trump. And if it does charge him, it can immediately end the trial by moving and voting to dismiss.

Increasing the possibility of such outcomes is the complex list of more than one hundred arcane rules of such a trial written in 1986. These threaten to convert a serious examination of presidential conduct into a months-long farce, with senators debating endlessly whether to adopt any or all of the existing rules or write a new set. Current rules call for “managers” to handle both prosecution and defense, allowing politicians or polemicists with no background in constitutional law to replace attorneys. Although Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts will be the “presiding officer,” he will have to “preside” without a judge’s conventional powers to “rule” on objections. Only the Senate can rule on them--by voice vote or, if demanded, roll call.

Before the trial can begin, existing rules call on senators to determine the “forms of oaths” each must take and the “forms for addressing managers.” They can set limits on the number of witnesses who testify, how long they can testify, whether they must stand or sit, when and whether to close Senate chamber doors to the public, and how to respond to “improper language.”

In the end, the trial of President Trump—if there is a trial—will reflect less on justice than on the will of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and his estimate of the trial’s possible effects on the 2020 presidential and congressional elections. In the end, he and his political advisors will determine the identity and number of many witnesses, the length of the “trial,” and—most significantly--whether Mr. Trump and his key aides and cabinet members testify.

In the unlikely event that the Senate convicts, the only penalty is removal from office, but the Constitution makes no provision for physically removing a president from his office or federal home if he refuses to leave. If he does leave, Mr. Trump would, as a private citizen, be subject to prosecution for the same crimes by federal authorities and, if found guilty, face fines and/or imprisonment, with the right to appeal.

Like the two previous presidential trials, however, the trial of President Donald J. Trump will be driven by politics, and the Senate, dominated as it is by senators from the President’s own party, will certainly acquit. Sensing the inevitability of such outcomes, Patrick Henry issued an impassioned warning against ratification of the Constitution as written:

“If your American chief be a man of ambition and abilities, how easy is it for him to render himself absolute! The president…can prescribe the terms on which he shall reign master...and what have you to oppose this force? My great objection to this government is that it does not leave us the means of defending our rights or of waging war against tyrants.”