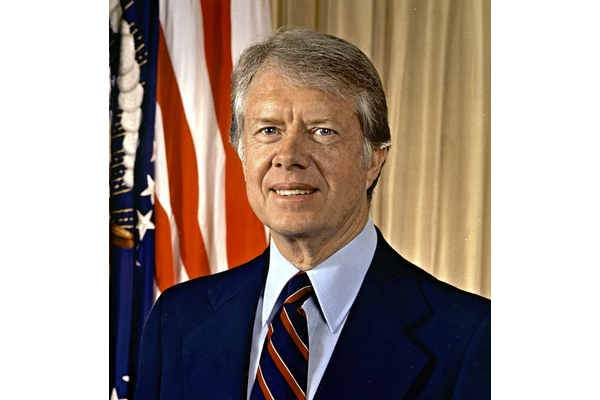

Jimmy Carter: The Last of the Fiscally Responsible Presidents

Popular impressions of Jimmy Carter tend to fall into two broad categories. Many see him as a failed president who mismanaged the economy, presided over a national “malaise,” allowed a small band of Iranian militants to humiliate the United States, and ultimately failed to win reelection. His final Gallup presidential approval rating stood at 34%—equal to that of George W. Bush. Among postwar presidents, only Richard Nixon (24%) and Harry Truman (32%) left office with lower approval ratings. As the political scientist John Orman suggested some years ago, Carter’s name is “synonymous with a weak, passive, indecisive presidential performance.” For those who hold this view, Carter represents everything that made the late ‘70s a real bummer.

His supporters, meanwhile, portray him as a unique visionary who governed by moral principles rather than power politics. They point out that he initiated a groundbreaking human rights policy, forged a lasting Middle East peace agreement, normalized relations with China, pursued energy alternatives, and dived headlong into the most ambitious post-presidency in American history.

Both perspectives have their merits. Yet although even Carter’s admirers would rather ignore his economic record than defend it, popular memory of his economy is off the mark. Contrary to the prevailing wisdom, by many indices the U.S. economy did relatively well during Carter’s presidency, and he took his role as steward of the public trust seriously. He kept the national debt in check, created no new entitlements, and steered the nation clear of expensive foreign wars. Whatever else one may think about the man, it is no exaggeration to say that Jimmy Carter was among the last of the fiscally responsible presidents.

Although there is no single measure for evaluating a president’s economic performance, if we combine such standard measures as unemployment, productivity, interest rates, inflation, capital investment, and growth in output and employment, Carter’s numbers were higher than those of his near-contemporaries Ronald Reagan, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and George H.W. Bush. “What may be surprising,” notes the economist Ann Mari May, “is not only that the performance index for the Carter years is close behind the Eisenhower index of the booming 1950s, but that the Carter years outperformed the Nixon and Reagan years.” Average real GDP growth under Carter was 3.4%, a figure surpassed by only three postwar presidents: John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, and Bill Clinton. Even though unemployment generally increased after the 1960s, the average number of jobs created per year was higher under Carter than under any postwar president.

Particularly noteworthy was Carter’s fiscal discipline. Although Keynesian policies were central to Democratic Party orthodoxy, Carter was a fiscal conservative who touted balanced budgets and anti-inflationary measures. By and large, he stuck to his campaign self-assessment: “I would consider myself quite conservative . . . on balancing the budget, on very careful planning and businesslike management of government.”

Under Carter, the annual federal deficit was consistently low, the national debt stayed below $1 trillion, and gross federal debt as a percentage of GDP peaked below forty percent, the lowest of any presidency since the 1920s. During his final year in office, the debt-to-GDPratio was 32% and the deficit-to-GDP ratio was 1.7%. In the ensuing twelve years of Reagan and Bush (1981-1993), the debt quadrupled to over $4 trillion and the debt-to-GDP ratio doubled. The neoliberal policies popularly known as Reaganomics had plenty of fans, but in the process of lowering taxes, reducing federal regulations, and increasing defense spending, conservatives all but abandoned balanced budgets.

The debt increased by a more modest 32% during Bill Clinton’s presidency (Clinton could even boast budget surpluses in his second term) before it ballooned by 101% to nearly $11.7 trillion under George W. Bush. Not only did Bush entangle the U.S. in two expensive wars, but he also convinced Congress to cut taxes and to add an unfunded drug entitlement to the 2003 Medicare Modernization Act. During the Obama presidency, the debt nearly doubled again to $20 trillion. (Obama and Bush’s respective totals depend in part on how one assigns responsibility for the FY2009 stimulus bill.) Under President Trump, the national debt has reached a historic high of over $22 trillion, and policymakers are on track to add trillions more in the next decade.

There are a few major blots on Carter’s economic record. Inflation was a killer. Indeed, much of Carter’s reputation for economic mismanagement stems from the election year of 1980, when the “misery index” (inflation plus unemployment) peaked at a postwar high of 21.98. The average annual inflation rate during Carter’s presidency was a relatively high 8% – lower than Ford’s (8.1%), but higher than Nixon’s (6.2%) and Reagan’s (4.5%). The annualized prime lending rate of 11% was lower than Reagan’s (11.6%) but higher than Nixon’s (7.6%) and Ford’s (7.4%). Economist Ann Mari May concurs that while fiscal policy was relatively stable in the Carter years, monetary policy was “highly erratic” and represented a destabilizing influence at the end of the 70s.

Carter’s defenders note that he inherited a lackluster economy with fundamental weaknesses that were largely beyond his control, including a substantial trade deficit, declining productivity, the “great inflation” that had begun in the late 1960s, Vietnam War debts, the Federal Reserve’s expansionary monetary policy, growing international competition from the likes of Japan and West Germany, and a second oil shock. “It was Jimmy Carter’s misfortune,” writes the economist W. Carl Biven, “to become president at a time when the country was faced with its most intractable economic policy problem since the Great Depression: unacceptable rates of both unemployment and inflation”—a one-two punch that came to be called “stagflation.”

In response, Carter chose austerity. Throughout the 1970s, Federal Reserve chairmen Arthur F. Burns and G. William Miller had been reluctant to raise interest rates for fear of touching off a recession, and Carter was left holding the bag. After Carter named Paul Volcker as Fed chairman in August 1979, the Fed restricted the money supply and interest rates rose accordingly—the prime rate reaching an all-time high of 21.5% at the end of 1980. All the while, Carter kept a tight grip on spending. “Our priority now is to balance the budget,” he declared in March 1980. “Through fiscal discipline today, we can free up resources tomorrow.”

Unfortunately for Carter, austerity paid few political dividends. As the economist Anthony S. Campagna has shown, Carter could not balance his low tolerance for Keynesian spending with other Democratic Party interests. His administration took up fiscal responsibility, but his constituents wanted expanded social programs. Meanwhile, his ambitious domestic agenda of industrial deregulation, energy conservation, and tax and welfare reform was hindered by his poor relationship with Congress.

The Carter administration might have shown more imagination in tackling these problems, but as many have noted, this was an “age of limits.” Carter’s successors seem to have taken one major lesson from his failings: The American public may blame the president for a sluggish economy, but when it comes to debt, the sky’s the limit.