The Social Psychology of Popular Right-Wing Conservatism

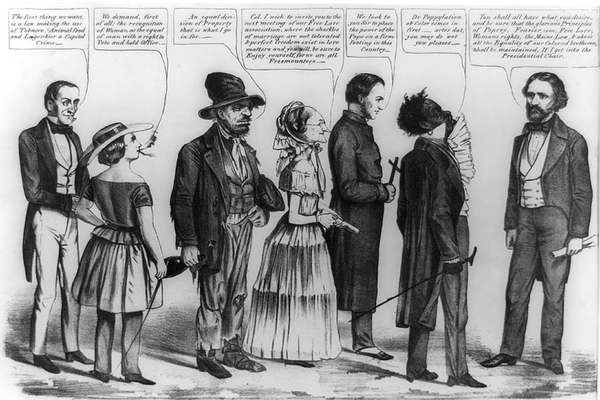

An 1856 cartoon depicts Republican John C. Fremont as a representative not only of abolition but of a host of threatening social movements

Many people who see little rational basis for supporting Donald Trump ask themselves: Why is he so popular? Relatedly, why did so many people support Richard Nixon, Adolf Hitler, and other avatars of popular right-wing conservatism? There are, of course, many different reasons for each situation. But there also key commonalities that have been identified in meta-analyses of the topic written by the psychologist John T. Jost and colleagues. In relation to Jost’s work, I have examined aspects of the antebellum South in order to better understand its political culture, especially aspects of that culture that prompted many Southerners to become more emotionally receptive to the appeals of “fire-eater” secessionist conservatives. More broadly, this historical lens can help illuminate the mass appeal of conservatism in general, focusing particularly on the psychological factors that tend to underlie this appeal.

For decades, antebellum Southern whites were exposed to a regular drumbeat of fearful rumors that bloody slave insurrections would result if slaves were emancipated, which rabidly pro-secessionist political leaders (the fire-eaters) contended would happen if Abraham Lincoln were elected president in 1860. This fear, along with racist attitudes toward African-Americans, reinforced the Southern white craving for order, the inclination to value the certainties that they felt they knew, and wariness about the possibilities of change.

Fear boosted the strength of leaders in politics, press, and pulpit whose cries about the dangers of slave revolt made people more inclined to emotion-based political decision-making rather than reason-based thought. In his role as one of the secession commissioners sent by the early-seceding states to coax other Southern states to join their cause, Stephen F. Hale of Alabama expressed many Southerners’ fears in portraying Lincoln’s election as “[inaugurating] all the horrors of a San Domingo servile insurrection [referring to the bloody slave liberation struggle during the era of the French Revolution in the country later known as Haiti], consigning her citizens to assassinations and her wives and daughters to pollutions and violation to gratify the lust of half civilized Africans.” Slave emancipation and equal rights for African-Americans would result in the obsessively-feared “amalgamation” of the races through interracial sex, or “an eternal war of races, desolating the land with blood, and utterly wasting and destroying all the resources of the country.” “With us [Southerners],” Hale observed, “it is a question of self-preservation. Our lives, our property, the safety of our homes and our hearthstones, all that men hold dear on earth, is involved in the issue.”

Contention over slavery was also part of a broader web of controversy arising from what many Southerners thought of as a decades-old culture war over the differing social arrangements and values of the North and South. Pointing to the fact that abolitionists were usually active in other reform movements in the North (that were virtually non-existent in the South), Southern leaders saw these movements as being of one piece with abolitionism, in dangerously seeking to extend the concept of human rights and opportunity to out-groups—often singling out the feminist movement in this regard—and in seeking to lure people away from traditional social relations and socioeconomic structures.

Southern leaders sought to stereotype reform activism as more radical and pervasive in the North than was actually the case. The historian Manisha Sinha observes that the North was portrayed as an atheistic land “in which property, marriage, female subordination, religious fidelity, and other pillars of social order were constantly challenged.” The fire-eater James D.B. De Bow on the eve of secession spoke of Southerners as “adhering to the simple truths of the Gospel and the faith of their fathers, they have not run hither and thither in search of all the absurd and degrading isms which have sprung up in the rank [Northern] soil of infidelity. They are not Mormons or Spiritualist [sic], they are not Owenites, Fourierites, Agrarians, Socialists, Free-lovers or Millerites.”

The South’s dominant approach to the Christian religion produced an atmosphere conducive to the fearful imaginings of a culture war, and reinforced the sorts of personality characteristics that Jost believes are conducive to the formation of right-wing conservative political beliefs. The tendency to demonize the North and its reform movements grew, in part, from a more general Manichean outlook emphasized within Southern churches, which divided the world into harshly drawn categories of good and evil. In this perspective, the only alternative to a slave-based traditional way of life in the South was considered apocalyptic ruin. Thus, the influential Rev. James H. Thornwell of South Carolina thundered that “the parties in this [cultural] conflict are not merely abolitionists and slaveholders—they are atheists, socialists, communists, red republicans, Jacobins, on the one side, and the friends of order and regulated freedom on the other. In one word, the world is the battle ground—Christianity and Atheism the combatants; and the progress of humanity the stake.”

Rather than pressing their congregants to realistically face the moral challenge of slavery, clergymen were crucial in helping Southerners circle their attitudinal wagons in defense of the peculiar institution, using a narrow literal interpretation of the Bible to defend it while insisting that the South had a God-given stable order far superior to that of the urbanizing “ism”-plagued North. Seeking to contain the moral ferment of the North and its potentially destabilizing effects, clergymen focused their congregants on personal salvation, shunning the direction of many Northern churches that sought to reform society in order to remove impediments to godliness.

Rather than seeking to treat certain passages of the Bible as allegory or historical custom in order to reconcile Scripture with more conscientious attitudes toward slavery (and to reconcile with scientific discoveries such as the geological findings proving a much older earth than that found in the Bible’s accounts), clergymen sought instead to squeeze reality into a rigid literal interpretation of the Bible. Thus, they offered their adherents a way of escape from the use of reason and dialogue in performing moral calculus, and demonstrated how to ground their beliefs and behaviors in what made them feel emotionally secure in the present. This helped hide the immorality of slavery from Southern eyes, and it hid the falsity of Southerners’ belief that their security depended on the continuation of slavery.

This religious approach reinforced the closed nature of a society in which dissenting viewpoints and the give and take of civil dialogue were only tolerated when concerning issues that did not challenge the structures of society. This was most particularly the case from the early 1830s onward, as the rise of abolitionism and other reforms prompted the highly defensive approach to issues that would mark the final decades of the antebellum era. Using the “isms” of the North as a foil, Southern right-wing leaders began to frame slavery as a “positive good,” in contrast to the previous view of slavery as a morally troublesome institution that was nevertheless too difficult to abandon due to economic and security concerns. Leaders thus placed the South on a fateful path, rejecting what had been a relatively open political culture in which civil discussion about weaning the South off slavery had been tolerated.

Believing themselves to be sitting atop a social volcano, Southern leaders sought order by isolating the region’s people from the culture of what they considered to be a decadent North and indeed from a decadent Western civilization in general. Psychological, economic, and physical bullying upheld the closed nature of the South, as did the forceful exclusion of antislavery newspapers, magazines, and pamphlets—backed by the federal government’s acquiescence in banning the distribution of supposedly incendiary works through the mail in Southern states. Those who voiced heterodox views could readily find their businesses shunned and their standing in society ruined. “Vigilance committees” filled with men itching to prove their masculinity sprang into action at rumors about whites advocating abolition and rumors that slaves may be planning to revolt. Many were forcefully exiled from the region, beaten up, or hanged as a result.

The suppression of thought in the antebellum South helped ensure that the individual dispositions of many whites would gravitate toward Jost’s categories of fear, dogmatism, intolerance of ambiguity, uncertainty avoidance, need for cognitive closure, and support for group-based dominance, all of which left many Southerners ill-equipped—in their lack of knowledge and in their fearful, conformist attitudes—to stand up to the fire-eaters during the secession crisis of 1860-1861. Seeking order above all, the South disallowed the possibility of evolutionary change from the 1830s onward, obtaining as a result bloody revolutionary change in the 1860s.

Ideally, more history and political science professors will recognize the value of using historical case studies as a lens for better understanding the psychology of right-wing conservatism, particularly in understanding its mass appeal. Given the propensity of right-wing conservatism toward authoritarianism, such a curricular element could help sensitize citizens to the potential danger that the emotion-driven inclinations characteristic of conservatism pose to the maintenance of a civil democratic polity. I would recommend the study of the social psychology of past right-wing political movements as a normative element in college-level U.S. history courses and other humanities and social sciences courses geared toward teaching the foundations of civic knowledge. Ideally, an awareness of the social psychological basis of right-wing conservatism might even suffuse down into the quotidian teaching of history and civics on a secondary school level. The ascendancy of Donald Trump illustrates how important it is to increase our citizens’ ability to take such historical issues into account in examining current events.