"I Imagine Everything Happened on Beale Street": Remembering Memphis in "Brother Robert"

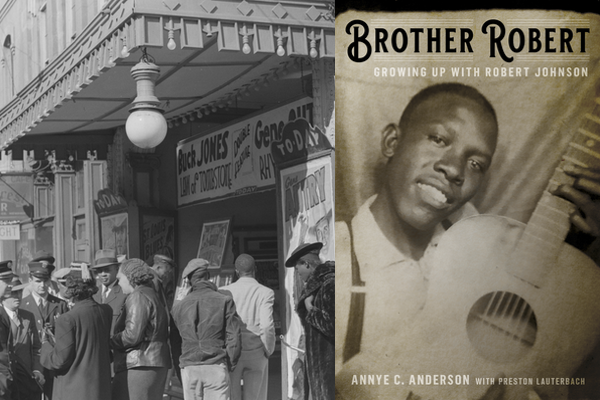

Palace Theater, Beale Street, 1939. photo Farm Security Administration

Cover image courtesy of Hachette Books, all rights reserved.

Excerpted from BROTHER ROBERT: Growing Up with Robert Johnson by Annye Anderson and Preston Lauterbach. Copyright © 2020. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

In BROTHER ROBERT: Growing Up with Robert Johnson, nonagenarian Annye Anderson sheds new light on a real-life figure largely obscured by his own legend: her kind and incredibly talented stepbrother, Robert Johnson. This book chronicles Johnson's unconventional path to stardom-from the harrowing story behind his illegitimate birth, to his first strum of the guitar on Mrs. Anderson's father's knee, to the genre-defining recordings that would one day secure his legacy.

Along the way, readers are gifted not only with Mrs. Anderson's personal anecdotes, but with colorful recollections passed down to her by members of their family-the people who knew Johnson best. Readers also learn about the contours of his working life in Memphis, never-before-disclosed details about his romantic history, and all of Johnson's favorite things, from foods and entertainers to brands of tobacco and pomade. Together, these stories don't just bring the mythologized Robert Johnson back down to earth—they preserve both his memory and his integrity.

For decades, Mrs. Anderson and her family have ignored the tall tales of Johnson "selling his soul to the devil" and the speculative to fictionalized accounts of his life that passed for biography. Johnson’s family is here to set the record straight.

In this excerpt, Annye Anderson recalls time spent with Robert and their older half-sister Carrie in Memphis, and the trends in music, movies and black politics that surrounded them.

I turned ten years old in April of 1936. After that my little world began to grow. My mother hadn’t allowed me to hang around Beale Street. Prostitutes were everywhere during that time. Close by in some of the private homes, I have seen whites come out and pick up black women. I imagine everything happened on Beale Street. That’s why my parents didn’t want me down there. I was told never to go to Handy Park, they had everything over there, gambling, the bluesmen were over there. Brother Robert went over there when he got ready. That was a proving ground.

Little by little, I ventured farther from home and got to know the way to Beale. My old territory between Third and Fifth, Calhoun and the railroad, was only about two or three blocks each way. Beale Street was almost a mile from the house, but easy to reach, straight up Hernando Street.

My ticket out came from Sister Carrie, through Brother Robert. She got her buttons, thimbles, tape, and thread from Schwab’s, a big general store on Beale. Sister Carrie stayed behind that sewing machine day and night and sometimes she needed supplies. She tried sending Brother Robert out, but he’d never come back. I had to go and find him. When I got to Beale, I knew he was playing his guitar, I could hear it coming up the street. I knew his riffs. Nobody else was playing like Brother Robert.

I have learned that he was contemporary while the others played classic blues. Wasn’t any Duke Ellingtons out on the street. Everybody was exposed to blues. The jug bands paraded through our neighborhood, and the children would follow just like the pied piper. They marched with their jugs and all that. Children danced to the music. Brother Robert took no interest. He wanted modern. Brother Robert didn’t sound like the jug bands or the Tampa Red I heard coming out of Ms. Lola Myers’s house. He worked to distinguish himself.

When Brother Robert went to Beale Street, he ended up playing in Handy Park. He and Son teamed up and played there as a duo, as well. He was well known at the One Minute Café, next door to the Palace on Beale, and played there, thanks to my family’s friendship with Mr. Pete, part-owner.

A block east of Handy Park was Church’s Park, named after Robert Church, the South’s first black millionaire and real founder of Beale Street. While Handy Park could be a little rough, Church’s Park appealed to the entire community. Teachers often held educational programs there and rehearsed and staged school plays in the auditorium.

Children could go and get some athletic instruction. One professor taught boys to box, including Sister Carrie’s son Lewis, who became a professional welterweight. The park had a public pool for black kids, though no lifeguards. The atmosphere there would be upbeat and wholesome. Brother Robert met up with his buddies. They read the paper and learned about the politics of the day. Robert Church Jr. was one of the leading black politicians of the time, and he had a strong presence. Brother Robert would learn about the news from Ethiopia and hear about people like Paul Robeson, Marian Anderson, and Paul Laurence Dunbar. Of course everyone idolized Joe Louis and saw his victories as something bigger than boxing, and you could speak safely about such topics at Church’s Park. Brother Robert had a girlfriend in that area named Pearl. She was dark brown with a gold crown on her front teeth, slender and about five-foot-six.

Once I got to go to Beale Street, I’d tag along with Brother Robert, Brother Son, and Sister Carrie to the movies at the Palace Theatre. They liked to see Mae West and Bette Davis, and I was a nuisance, always running to the bathroom and wanting popcorn.

Most of the movies we saw at the Palace were Westerns. Buck Jones and Tom Mix were Brother Robert’s favorite cowboys. He wore that big Stetson, like them. All of the young men in our family wore Stetson—that was on the go. My father and Uncle Will wore Dobbs.

At the Palace, Son and Brother Robert saw Gene Autry in Tumbling Tumbleweeds. Gene and another guitar player did a song called “That Silver-Haired Daddy of Mine.”

That piece became a part of Son and Brother Robert’s repertoire whenever they entertained.

All the top bands, Count Basie, Lionel Hampton, Lucky Millinder, Cab Calloway, and Jimmie Lunceford played at the Palace. We could see big entertainment for a small price. These acts also played the Orpheum, the grand opera theater on Main Street at Beale, one of the few integrated venues in the city, though blacks sat in the balcony.

It’s my understanding that Brother Robert would hang out at the Palace while waiting on his next gig. Mr. Barrasso, the owner, let you stay all day on one ticket price. Brother Robert would sleep while the movie played over and over, and the Looney Tunes, shorts, and newsreels ran. He’d sit with the guitar across his chest, watching the old-time cowboy movies. He’d cool off in there on a hot day or warm up on a cold day until the time to meet up with his friends or return to Sister Carrie’s.

....

Brother Robert spoke at times of Haile Selassie, emperor of Ethiopia. He knew about the NAACP and kept up with the Scottsboro Boys case—the people involved had been hoboing to Memphis, just like Brother Robert often did. He followed Paul Robeson’s activism and enjoyed Robeson’s movie Show Boat. He was no dummy, he read the paper. You can hear his awareness of racism in his music. He doesn’t want sundown to catch him where he isn’t supposed to be. He’s telling you something. He knows if you get wrong in the white folks’ neighborhood, they’ll harm you. White folks are afraid. We were riding out to pick cotton and went up in the wrong yard. We looked up and saw a man with his shotgun pointed right at us, and we backed right out.