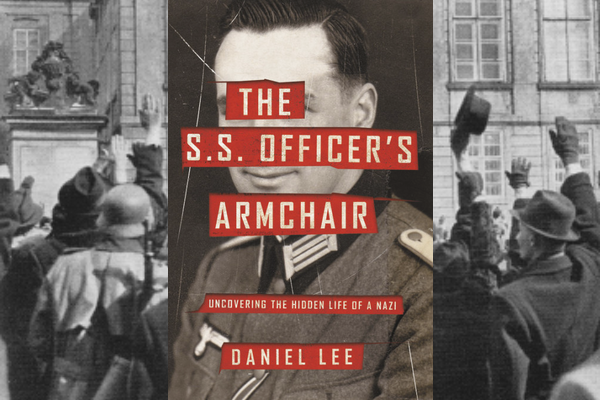

The SS Officer's Armchair

Cover image courtesy Hachette Books. Germans salute occupied Prague Castle, March 16, 1939.

In 2011 an upholsterer in Amsterdam found a bundle of swastika-covered documents inside the cushion of an armchair he was repairing. The papers all belonged to Dr. Robert Griesinger, a lawyer from Stuttgart who had been an SS member working for the Reich in Nazi-Occupied Prague. Jana, the armchair’s Czech owner, did not recognise Griesinger. She had purchased the chair while a student in Prague in the 1960s, and it was one of the few objects she brought with her to the Netherlands in the 1980s, when she obtained permission for her family to leave Communist Czechoslovakia. As a professional historian of the Second World War, I was asked to investigate. I immediately set out to uncover more about this Dr. Griesinger, who was not mentioned in any books on occupied Prague or anywhere online. Did he survive the war? And, of course, how did his most precious documents end up hidden inside a chair, hundreds of miles from Prague and Stuttgart? The very ordinariness of this man who, like thousands of ordinary Nazis had vanished from the historical record, made him all the more intriguing to me. I wanted to see whether following the trajectory of an anonymous man could reveal anything new about life under the Third Reich.

My search for Griesinger was to last five years. It would lead me German provincial towns where he had studied and worked and to archives and libraries across Europe and America. I discovered early on that Griesinger was not as German as I had thought and that his father, born in New Orleans, came from a family that owned enslaved people in Louisiana. I later managed to track down his daughters, and even read his mother’s diary. Through the lens of a single object, I was able shed new light on a period of history we think we know so well, exposing how ordinary Nazis such as Griesinger were active participants in Nazi terror and how choices made at the time reverberate into present-day Germany, especially among Griesinger’s descendents and the rest of the generation of children born during the Nazi period. But I also discovered that Griesinger is entangled in my own family’s history of the war. Growing up Jewish in 1980s London, I had often heard that some of my grandmother’s relatives in Ukraine were not heard from again after the Second World War. Despite my professional interest in the Holocaust, I never thought to learn more about them or their fate: I did not even know their names.

Everything changed when I discovered Griesinger was involved in the attack on Ukraine in June 1941, when Hitler surprised the world by invading his former ally, the Soviet Union. I suddenly became more interested in my family’s history when I uncovered from military sources details of the terror Griesinger’s division unleashed on the civilian population – including Jews – only days after entering Ukraine. For decades after the war much of the German public believed, and were so encouraged by some historians, that front-line infantry divisions such as Griesinger’s generally behaved well in Ukraine as they fought heroically against the Red Army; in this view only the Einsatzgruppen and Sonderkommando, the specialist police and security battalions, were responsible for mass shootings.

This was not the case. As Griesinger’s division sped east towards Kiev, some soldiers took part in the execution of Jews. My pursuit of Griesinger prompted me to ask questions about my own family, just as I had been quizzing Griesinger’s daughters about theirs. I visited my grandmother at her London home to find out about Stavyshche, the small shtetl in which Israel Pougatch, her father, was born. In 1907, Israel’s father Tsudik, relocated his young family from Ukraine to settle in the East End of London. Tsudik left behind his parents and three younger siblings: a sister, Rayza, and two brothers, Zelman and Moishe. My grandmother remembered seeing the letters that went back and forth between Tsudik and his siblings. She knew that Rayza, Zelman and Moishe did not emigrate west. They remained in Ukraine on the eve of the war and were never heard from again.

The more I uncovered about Griesinger, the more I wanted to learn about my own family. With new knowledge of the Pougatch family, I took out a large map of Ukraine and placed it on my dining-room table. Using coloured drawing pins, I began to plot the route that the 25th Motorised Infantry Division took to Kiev in July 1941, putting in pins to mark the towns along the way: Rivne, Novohrad-Volynskyi, Zhytomyr. Fortunately, Stavyshche, in the district of Tarashcha, was so far to the south of Kiev it seemed unlikely Griesinger would have passed through it. But I was mistaken, for his army unit unexpectedly veered south and ended up in Tarashcha in late July 1941. For a fleeting moment Griesinger experienced the same sights and sounds that for centuries had provided rhythm and familiarity to my ancestors’ everyday lives. In the days that followed Tarashcha’s occupation by Griesinger’s unit, professional killing squads were brought in to murder the district’s entire Jewish population. After two years on Griesinger’s trail, I felt discomfort for the first time. Following his trajectory had brought our histories together: in a chilling coincidence, it led me to the destruction of my ancestral shtetl and the extermination of its inhabitants by Nazi bullets or those of their Ukrainian accomplices.

After the Red Army liberated Kiev in November 1943, it did not take long for news to trickle into London about the massacres that took place in Ukraine two years earlier. Since Tsudik Pougatch’s siblings and their families were never heard from again, their violent fate seemed certain. Tsudik was left with little doubt over what became of them. He was so certain of the fate of Rayza, Zelman and Moishe Pougatch that he did not try to find out whether they survived. A search on the International Tracing System (ITS), reveals that neither Tsudik, nor anyone else, ever launched an investigation to look for his lost relatives. Had he done so, he might have discovered a shocking revelation.

Tsudik Pougatch went to his grave in 1960 mistakenly thinking his family had been murdered. After learning their names, I researched what became of Rayza, Zelman and Moishe Pougatch, during the Second World War, eventually finding them in records at Yad Vashem, Israel's official memorial site and research center on the Holocaust. Griesinger’s eyes did not meet those of my relatives as he made his way across Ukraine in the summer of 1941. The Pougatch family was spared the devastation that Griesinger’s associates inflicted on the community of Stavyshche. The most detailed information at Yad Vashem concerned Zelman Pougatch, which revealed that the sixty-year-old weaver survived the Holocaust thanks to his son-in-law, Boris Skuratovsky. In response to the German invasion, the USSR evacuated its industrial resources thousands of miles east. 283 industries were evacuated from Ukraine, including staff, machinery and equipment. Factory workers such as Boris were allowed to take with them not only their spouses and children, but also, their parents and, even, their parents-in-law. Along with some sixteen million Soviet citizens who fled or were evacuated east into Russia and Central Asia, the Pougatch and Skuratovsky families were evacuated to Zelenodolsk, an industrial town on the great Volga river in Tatarstan, five hundred miles east of Moscow. Zelman owed his life to his son-in-law.

After months desperately trying to find out what became of Zelman Pougatch after his evacuation to Zelenodolsk, I eventually discovered a 2016 Yahrzeit notice placed in the newsletter of a synagogue in Ventura, California [Every year, Jews remember deceased relatives by lighting a candle on their Yahrzeit, the anniversary of their death]. The notice was placed by his grandson, Boris Skuratovsky’s son. Not only did Zelman Pougatch’s family survive the Holocaust by bullets in Ukraine, but they also managed to survive the evacuations to the east. At some point after the war they must have moved to America.

Everything was moving so fast. Only a short time earlier, I believed I was looking for the final resting place of my relatives who had vanished during the Second World War without trace. Now all of a sudden, I had the name of one of their descendants living in California. It did not take long for me to contact them and within a few months I was sitting in a kitchen in San Francisco with Vera, the grandchild who knew Zelman best. Vera was in her early seventies and worked as a bookkeeper at the same company for the past thirty-five years. She was one of 125,000 Soviet Jews who settled in the United States during the 1970, when, in the spirit of détente, Soviet authorities increased emigration quotas.

Vera’s knowledge of her grandfather and his siblings put closure on a family mystery that had seemed unsolvable. She told me that Zelman returned to Kiev at the end of the war and died in the 1960s. Reyza, Zelman and Tsudik’s sister, also returned after the great evacuation to the east. Instead of settling in Kiev, Reyza went back to the district of Tarascha, the land of our ancestors, the place where she, Tsudik, Zelman, and the other Pougatch children were born. Reyza set up her postwar life in a portion of western Ukraine that contained only a handful of Jews. Having lost her husband in the war, she wanted time to take stock of her life. As a Yiddish speaker, with only rudimentary Russian, she was able to isolate herself further from the local community. When she died in 1962, Reyza, as the final guardian of Pougatch family lore in Tarascha, took with her the last remaining memories of an important chapter of our family history on the eve of the Holocaust.

After we had spoken for an hour, Vera insisted I stay for dinner. Vera made a toast for the occasion. Not since Tsudik left Ukraine for London in the first decade of the twentieth century had our two branches of the Pougatch family sat around a table together. Just as she was about to take a sip from her glass, she turned to me and said, “You know, if it wasn’t for a Nazi, we would never have met.” She was right.