For Deep and Lasting Reform, We Need to Amend the Constitution

In the aftermath of nationwide protests unlike any seen in a generation, an extraordinary window of opportunity may be opening to address some fundamental problems in our country. People are understandably focused on ideas to bring about better policing. Health care and economic inequality will surely return to the agenda as we proceed into the party conventions and fall election season. But with a reform movement this large underway, we should focus new attention on the root causes of political division and anger at our broken system. These lie in outdated parts of the Constitution itself that desperately need to be amended.

Improving our elections with a rotation of early primaries among all our states, automatic runoffs on ranked-choice ballots, fair district lines, and uniform federal requirements for election integrity is best done through constitutional amendments. Otherwise our courts will continue to allow all kinds of manipulations by state officials, including the radical gerrymandering of our House districts.

Likewise, reducing the bloated power of monied interests in our elections requires overturning the Citizens United precedent through an amendment that establishes voter-owned elections with public financing of campaigns, very strict limits on all private donations, and requirements for candidates in all federal races (and all cabinet appointees) to disclose ten years of tax records. The amendment should include a clear statement that corporations—whether for-profit or nonprofit —do not have the same rights to spend on “speech” as real persons. Political advertising by corporations and large PACs should be strictly limited.

Because such an amendment focuses on ending corruption and upholding the integrity of the process, it could enjoy wide support across the political spectrum, even if large corporations hate it. The same holds for an amendment to build “a big, beautiful wall”—not between the US and Mexico, but instead between Congress and businesses and nonprofit lobbies that seek to control it. We need a minimum ten-year gap between serving in Congress and working for a lobby or corporation whose interests were directly benefited (in some quantifiable measure) by legislation one backed by a former member. Appointed federal officials should also be banned from going straight into government positions that involve regulating the industries they came from. We should also restrict access of paid lobbyists to federal officials, and use corporate tax law to limit the armies of lawyers that the biggest companies use to outgun all government efforts to regulate them. Big corporations and their lobbies would fight these amendments like hell, but they would face a truly enormous populist movement even more hell-bent on getting them ratified.

The legislative process also badly needs reform to break the endless gridlock that has so baffled and enraged Americans of virtually all political persuasions. If we truly believe that the majority should rule, then the Senate filibuster should be made unconstitutional. This tactic, which only became common in recent decades, prevents even strong majorities in national elections from seeing proposals they support enacted into law. The filibuster is not in the Constitution because it is a total violation of the “grand compromise” of 1787: it inflates minority rule well beyond what our larger states agreed to. With filibusters, senators representing less than 30 percent of Americans can and often do block legislation that most voters supported during the last election. We should add an amendment for the House enabling a petition of 55 percent of House members to force an issue to a full vote. This would reduce House leaders’ power to block legislation that could easily pass with broad bipartisan support.

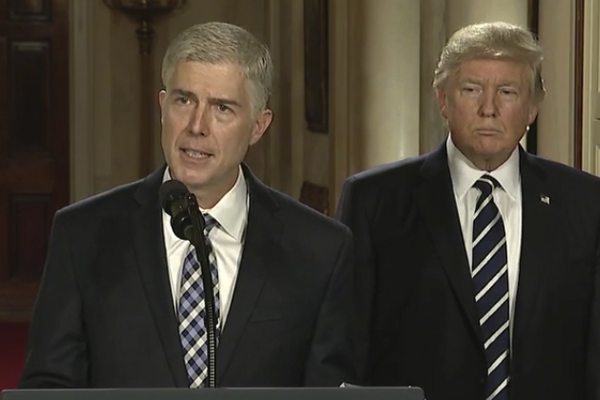

These reforms would make elections effective and facilitate compromise legislation. Even more popular would be an amendment to set 18-year terms in the Supreme Court so that exactly two new justices are appointed during each four-year presidential term to replace those who reach their term limit. If a justice retires early or dies, her or his term can be finished out by a justice from one of the federal appeals courts selected by lottery. Congress should also be required to vote on these and other judicial appointments within six months.

There remains the issue of increasing abuses of power in the presidency. Americans generally believe in having a strong chief executive, but links with Russia and Ukraine-gate have revealed deep problems. This issue should not be a partisan one: we need amendments to clarify what kinds of collusion with foreign powers constitutes treason, and to clarify when a sitting president can be charged with a crime. No president or campaign for federal office should be able to seek or accept any type of campaign assistance from foreign powers or their operatives, especially by data theft. Congressional subpoena power should be strengthened, contempt of Congress defined as a felony, and the limits of executive privilege defined. Grounds for impeachment and the impeachment process should be spelled out in more detail. And presidents and cabinet officials should be required to hold all assets in blind trusts.

We must also set some reasonable limits to presidential power within the executive branch itself. Quite a few delegates to the original constitutional convention wanted a cabinet with powers to override the president in some instances. Today we should be more worried about protecting the rule of law. The attorney general and director of the FBI should have ten-year terms and should be protected from early presidential dismissal without the concurrence of three-fifths of the Senate. More generally, the professional nature of the civil service should be constitutionally protected: people should be hired into federal administrative positions only based on their qualifications, not political loyalties, and close family members of the President and cabinet (by birth and law) should be banned from holding executive office. Some minimum professional credentials might even be set for cabinet and undersecretary appointments as well. And it is long past time to allow immigrants naturalized for over twenty years to serve in our highest office.

After the upheavals of June, we may now have a once-in-a-lifetime chance to get to the constitutional roots of so many national problems. We must fix policing and achieve racial equality in the criminal justice system. But it would be crazy to stop there when we may now be able to build a broad coalition for reforms that could transform the whole nature of our politics by restoring democratic control of law and policy making.