Free Speech and Civic Virtue between "Fake News" and "Wokeness"

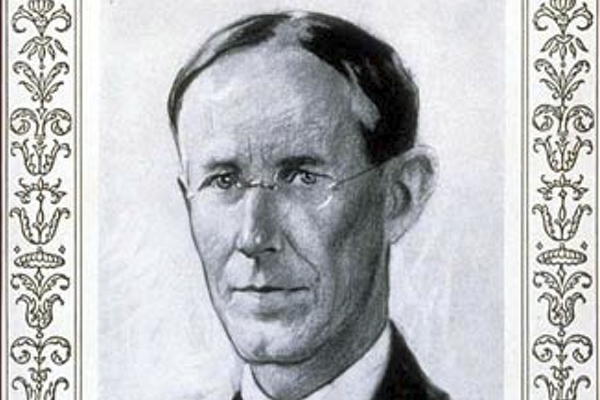

Alexander Meiklejohn, Time, 1928

Harper’s Magazine recently published an open letter defending public inquiry and debate against “severe retribution [for] perceived transgressions of speech and thought.” The letter refers to “an intolerant climate that has set in on all sides,” and while it mentions Donald Trump and authoritarian regimes its real target seems to be an increasingly illiberal segment of the American Left.

Critics have cried foul. Some reactions have exhibited exactly the tendencies that the letter describes, but others thoughtfully critique power imbalances between the celebrity signers and members of various marginalized groups, or question the motives or consistency of those signers who (in their eyes) have not supported free speech in the past. Some even claim the mantle of liberalism for themselves, arguing that public pressure to suppress unpopular opinions is itself a form of collective speech or association, the very “marketplace of ideas” that many liberals celebrate.

Unfortunately, none of these arguments reaches past adversarial notions of democracy. They all characterize free speech as a matter of conflicting rights-claims and competing factions. Indeed, some critics of the Harper’s letter seem eager to reduce all public debate to a form of power politics. Trans activist Julia Serano merely punctuates the tendency when she writes that calls for free speech represent a “misconception that we, as a society, are all in the midst of some grand rational debate, and that marginalized people simply need to properly plea our case for acceptance, and once we do, reason-minded people everywhere will eventually come around. This notion is utterly ludicrous.” As long as political polarization precludes rational consensus, she argues, we are left to “[make] personal choices and pronouncements regarding what we are willing (or unwilling) to tolerate, in an attempt to slightly nudge the world in our preferred direction.” Notably, she makes no mention of how we might discern the validity of those preferences or how we might arbitrate between them in cases of conflict.

To paraphrase the philosopher Alexander Meikeljohn, one could say that critics of the Harper’s letter take the “bad man” as their unit of analysis. By their lights, all participants in public debate are prejudiced, particular, and self-interested, “idiots” in the classical sense of the word. This is what allows many of the critics to assert a moral equivalence between free speech and the suppression of ideas. Free speech advocates are hypocritical or ignore some extenuating context, they claim, while those stifling disagreeable or offensive views are merely rectifying past injustices or paying their opponents back in kind, operating practically in a flawed public sphere.

It is telling, however, that the letter’s critics focus on speakers and what they deserve to say far more than the listening public and what we deserve to hear. Indeed, their arguments seem to deny the very existence of a public (at least in a unitary sense), and that is their fundamental shortcoming.

In Free Speech and Its Relation to Self-Government (1948), Meikeljohn challenges us to approach public discourse from the perspective of the “good man”: that is to say, the virtuous citizen. For Meikeljohn, if political debate is nothing but an exercise of “self-preference and force,” oriented toward no “ends outside ourselves,” we have already lost sight of its purpose (pp. 78-79). One cannot appreciate the freedom of speech, he writes, unless one sees it as an act of collective deliberation, carried out by “a man who, in his political activities, is not merely fighting for what…he can get, but is eagerly and generously serving the common welfare” (p. 77). Free speech is not only about discovering truth, or encouraging ethical individualism, or protecting minority opinions—liberals’ usual lines of defense—it is ultimately about binding our fate to others’ by “sharing” the truth with our fellow citizens (p. 89).

Sharing truth requires mutual respect and a jealous defense of intellectual freedom, so that “no idea, no opinion, no doubt, no belief, no counter belief, no relevant information” is withheld from the electorate. For their part, voters must judge these arguments individually, through introspection, virtue, and meditation on the common good.

The “marketplace of ideas” is dangerous because it relieves citizens of exactly these duties. As Meikeljohn writes:

As separate thinkers, we have no obligation to test our thinking, to make sure that it is worthy of a citizen who is one of the ‘rulers of the nation.’ That testing is to be done, we believe, not by us, but by ‘the competition of the market.’ Each one of us, therefore, feels free to think as he pleases, to believe whatever will serve his own private interests. We think, not as members of the body politic, of ‘We, the People of the United States,’ but as farmers, as trade-union workers, as employers, as investors.…Our aim is to ‘make a case,’ to win a fight, to make our plea plausible, to keep the pressure on” (p. 86-87).

Of course, this is precisely the sort of self-interested posturing that many on the Left resent in their opponents, but which they now propose to embrace as their own, casually accepting the notion that their fellow citizens are incapable of exercising public reason or considering alternative viewpoints with honesty, bravery, humility, and compassion.

As in many points of our history, the United States today has its share of hucksters, conspiracy theorists, and hate-mongers. It would be a mistake, however, to conceive of either our democratic practice or ideals as if these voices were central or unanswerable. In practice, curtailing public speech is likely to worsen polarization and further empower dominant cultural interests. As an ideal (or a lack thereof), it undermines the intelligibility and mutual respect that form the very basis of citizenship.

The philosopher Agnes Callard points out that political polarization has induced Americans to abandon “truth-directed methods of persuasion”—such as argumentation and evidence—for a form of non-rational “messaging,” in which “every speech act is classified as friend or foe… and in which very little faith exists as to the rational faculties of those being spoken to.” “In such a context,” she writes, “even the cry for ‘free speech’ invites a nonliteral interpretation, as being nothing but the most efficient way for its advocates to acquire or consolidate power.” Segments of the Right have pushed this sort of political messaging to its cynical extremes—taking Donald Trump’s statements “seriously but not literally” or taking antagonistic positions simply to “own the libs.” Yet none of that justifies the countervailing impulse to cloak messaging in sincerity of conviction.

While the language of the Harper’s letter has been criticized as vague, the responses to it could not be clearer. Critics have endorsed an adversarial politics based on the “marketplace of ideas” and selective elements of liberalism. Signers have put forward robust liberal principles that align with republican virtues. When they warn that restriction of debate “makes everyone less capable of democratic participation,” they affirm civic equality and public duties. When they refuse “any false choice between justice and freedom,” they underscore that freedom is hardly “intellectual license” (p. 87) but a shared commitment to realizing our society’s ideals. Rather than assuming the supremacy of our own opinions or aspersing the motives of those with whom we disagree, our duty as Americans is to think with, learn from, and correct each other. If we are to decide what we are willing or unwilling to tolerate, we must do so with individual integrity and collective concern.