Andrew Rotter's "Sensual Empires: Britain and America in India and the Philippines"

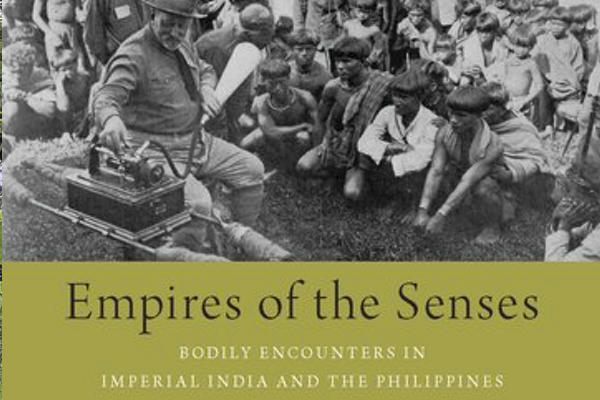

The five senses help us navigate nature but, according to historian Andrew J. Rotter, they can also help construct an empire. Rotter is the Charles A. Dana Professor of History and Peace and Conflict Studies at Colgate University. His book Empire of the Senses: Bodily Encounters in India and the Philippines uses sensory history to compare the British and American empires side-by-side. Oxford University Press published the book in 2019 and they did a lovely job in producing a sensory experience for the reader. High quality paper and a dust cover with an attractive but calming green hue and two evocative images that would make for fine memes of the book in social media. Much work goes into designing covers and OUP artists did well to create a book with colors and lines that speak to organization and innovation.

Organization and innovation is what describes the content as well. Rotter was inspired by sensory historian Mark Smith, who has done much to take the ideas of French historian Alain Corbin and apply them to the American context. Corbin’s examinations of perfume and bells in nineteenth century France laid the groundwork for a whole generation of sensory historians and Smith’s recent The Smell of Battle and the Taste of Siege--a sensory history of the Civil War--places him in this genre. Recently sonic history and aural studies including deaf studies have attempted to accentuate the ear’s role in a historical genre that, at least since the Enlightenment, has tended to privilege the visual power of the eye. Recovering the history of the other non-visual senses is sometimes posed as a critique of enlightenment histories. Histories that privilege the senses that do not rely on the eye are often very difficult to write because primary sources such as newspaper accounts or journal writers do not often take the time to fill their accounts with such descriptions. But doing the hard work of finding sources with sensory information is important to history. Not only does it allow us to recover histories that Enlightenment historians have neglected in their obsessed pursuit of the visual, but humans interpret the environment through the five senses. All five are necessary to make sense of the world and as new discoveries in how human memory works suggests, our minds uses these five senses interdependently to understand social constructions of reality and to make memories.

Andrew Rotter takes advantage of how our senses work with our minds to explain how British and Americans colonized far away lands in India and the Philippines. He divides his book into chapters that focus on each sense: seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, and touching. By organizing his book around the senses Rotter has to sacrifice chronology. It can be a difficult comparison to make for as much as Britain and America are culturally and politically similar, their imperial visions were profoundly dissimilar. The British empire, for example, recognized difference in colonial subjects and often governed as if certain rules that applied to people in India did not apply to the British because of this difference. Americans governed the Philippines with the design of making Filipinos into Americans: rules tended to be applied more evenly to everyone, at least theoretically. A seasoned historian, Rotter more than understands this dichotomy and each chapter actually works well within this contrast. British and Americans govern colonized subjects differently even as imperial agents apply similar methods to subdue large populations. What gives the senses life is Rotter’s reliance on Edward Said’s concept of Orientalism. The idea that Said presented in his infamous work on the relationship between the Orient (The East) and the Occident (The West) is that Westerners often defined people who lived in non-Western places through history, art, and literature. This, Said contends, is a powerful way to build colonial regimes and perpetuate racial stereotypes, through cultural reproduction. Other historians, such as Paul Kramer, have picked up on this idea. Kramer argues in The Blood of Government, that Americans, not people who lived in the Philippines, created the idea of being Filipino through their governing by racial stereotypes. Rotter argues that this kind of Orientalism was created through British and Americans trying to regulate, control, and even reinvent the senses of Indian and Filipino people. The book is filled with all kinds of extraordinary stories of Westerners going to India or the Philippines and being absolutely aghast at the sensory attack on their own western values. Colonized peoples needed to be colonized, argued imperialists, because they had no understanding of how enlightenment senses were supposed to be used. The trick for civilizing barbarians, they argued, was civilizing the barbarians senses.

Here is Rotter’s second major theoretical influence: Norbert Elias’s The Civilizing Project. Elias examines Western European cultural practices, seemingly as trivial as blowing noses and using eating utensils, to suggest that nation states emerged out of the middle ages at moments when elite culture, manners, and “civilized” behavior began to permeate society. As civilized culture took root, nations broke from the medieval norms. Although Eurocentric and dated, Rotter uses Elias’s notion of the civilizing process not to describe how the British or Americans tried to give birth to new nations in India and the Philippines. Rather, he attempts to decolonize The Civilizing Project and use Elias to describe westerners' attempts at colonization. Rotter’s coupling of Elias with Said may seem strange at first, but it pays dividends again and again in each chapter. Whether using the sense of sight to condemn the diseased or the over-sexualized, taste to distinguish “colonial” food from healthy food, smell to sense the location of disease and poor hygiene, hearing to control political speech, or touch to control the sexuality of the colonized, British and American colonizers built their empires through what they sensed in India and in the Philippines.

This was not a one-way process, however, colonists struck back against the imperial senses. Though many Britons had misgivings about curry, Indian people changed the tastes of the colonial overseer seducing their colonizers through their food. Colonizers and colonized mixed sexually too. Many Brits and Americans brought Indian or Filipino food and customs home with them and incorporated them into American society as time went on. Sometimes the very senses that Westerners produced became objects of resistance and even protest. Mutiny in the Sepoy Rebellion being just the most obvious example in India. Rotter showcases well how colonizers often become colonized by the very senses that the colonizers were trying to colonize.

Rotter did not show the inter-imperial exchange and learning as well as I would have liked. While it appears that imperialists looked at each other from afar, it remains unclear how intimately and how much Britons and Americans directly learned from each other. How do imperial agents share information with each other and how do empires learn from other empires are questions that remain for further research. Rotter likewise alludes to the idea that imperial agents learn how to implement their empire of the senses in part from their experiences on the domestic front while they grow up in the core of the empire. Interpreting the senses in a colonial system thus is shaped not only by experiences in the frontier but also by past experiences in the core. If domestic and frontier landscapes are linked in imperial practices then an imperial memory of home must exist. While Rotter focuses solely on bodily encounters, how senses stimulate psychic memories to become imperialistic is an avenue for research that could be further explored by others. Finally Rotter’s focus on the anglophone world is insightful and important and hopefully it will inspire other similar comparisons in the francophone world or francophone-anglophone comparisons or other imperialistic comparative studies.

Overall Empires of the Senses provides a fascinating comparative exploration of how the senses work within two imperialistic regimes. It is a worthwhile read for historians, graduate students, and the general public interested in sensory history, food, disease, or empire-building in the anglophone world.