Judicial Overreach in High Partisan Times: How the Dred Scott Decision Broke the Democrats and Boomeranged on the Court

With the imminent confirmation of Amy Coney Barrett, Republicans appear to have a solid Supreme Court majority in their grasp. But they –and the conservative Supreme Court majority— ought to heed a lesson from the Court’s history: Beware of overreaching.

The most dramatic example comes from the Court’s most infamous case. We usually parse Dred Scott v. Sandford as the Worst Decision Ever, but it also offers an overlooked political lesson. The Court waded into a high partisan battle and badly damaged the institutions behind the ruling. The Democratic Party broke in two and the Supreme Court itself endured a decade of court packing.

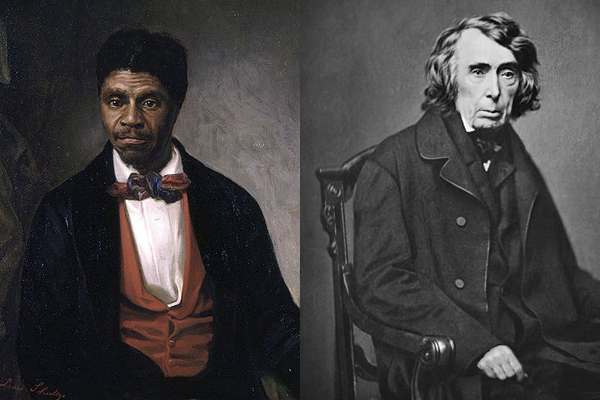

Start with the case itself. An army surgeon was posted to the free territory of Wisconsin and took along a slave named Dred Scott. While in the territory, Scott married in a civil ceremony – something he could not have done as a slave. When the army sent the doctor back into slave states, Scott sued for his family’s freedom (by now they had two daughters) citing the traditional legal rule, “once free, always free.” After a 12-year legal saga through state and federal courts, Chief Justice Roger Taney decided to use the case to settle the fiercest question of the 1850s: Which of the vast western territories should be open to slavery?

Democratic President James Buchanan, who never missed an opportunity to side with slaveholders, used his inaugural address to cheer the awaited court decision as the final word on the matter. Like all good citizens, intoned this soul of innocence, “I shall cheerfully submit … to their decision … whatever it may be.” Except that he already knew perfectly well what it would be. Buchanan had pushed Justice Robert Cooper Grier (a fellow Pennsylvanian) to join with the five southern justices in order to improve the optics when the legal bomb detonated.

Two days later, on March 6, 1857, the Supreme Court announced its ruling in Dred Scott v. Sandford, an historically inaccurate, legally implausible, virulently partisan decision marked by eight different opinions (two dissenting). A clerk even misspelled the plaintiff’s name –it was Sanford, not Sandford-- so that even the name of this infamous decision memorializes a typo.

At the heart of all the jurisprudence sits Justice Taney’s majority opinion, an implacable picture of race and exclusion. The Constitution and its rights could never apply to Black people. What about Scott’s claim to have lived in a free territory? Not valid, ruled Taney, and for a blockbuster reason: no one had the authority to prohibit slavery in any territory – not the federal government, not the residents of the territory, not anyone. What about the Missouri compromise of 1820 which forbade slavery above the 36 30’ parallel? “Not warranted by the Constitution and therefore void.” How about the compromise of 1850 and the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which had turned to popular sovereignty? Nope. No one could limit slavery in any territory.

The political fallout quickly spread to both the parties and the courts. The Republicans had sprung up, in the mid 1850s, to stop the spread of slavery into the territories. The Dred Scott decision, which was the first to strike down a major act of Congress in more than half a century, ruled out the party’s very reason for being. As historian George Frederickson put it, the ruling was “nothing less than a summons to the Republicans to disband.” Republican leaders denounced the Court as part of the Slave Power and accused Chief Justice Taney of conspiring with pro-slavery Democrats in the White House and Senate. The decision itself helped propel these new-found enemies of the court to power.

Across the party aisle, the detonation unexpectedly wrecked the Democrats. At their next political convention, in 1860, they paid the price of their victory. When it came time to write a party platform, northern Democrats opted for the same slavery plank they had used during the last presidential election: White men in the territories should decide the slavery question for themselves. After all, these politicians could not very well go before their voters –who were eager to claim western lands for white men and women-- and announce that every territory was open to slavery regardless of local opinion.

The southern Democrats, however, insisted on a plank that said exactly that. They bitterly denounced their party brethren for casually handing back what the Supreme Court had given. The southern version of the plank proclaimed that Congress had a “positive duty” to protect slaveholders wherever they went -- “on the high seas, in the territories, and wherever else [Congress’s] constitutional authority extends.” The high seas? A sly call to bring back the Atlantic slave trade which had been banned in 1808. When the convention narrowly chose the northern version of the platform, the southerners walked out of the convention and eventually nominated their own candidate.

A divided Democratic Party eased the way for a Republican victory in 1860 and that, of course, gave the nation a hard shove toward the Civil War. Democrats had dominated Washington throughout the antebellum period. Now they fell from power. They would not control the Presidency and Congress again for forty-two years.

The recoil from the Dred Scott decision also shook the Court. Lincoln bluntly expressed the Republican’s skepticism in his Inaugural Address. “The candid citizen must confess that if the policy of the government … is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court, the people will have ceased to be their own rulers.” The other branches of government were every bit as capable of enforcing the Constitution, he continued, and the Court had no business claiming that right for itself.

Republican Senator John Hale (NH) added that the Court “had utterly failed” and called for “abolishing the present Supreme Court” and designing a new one. The new majority did not quite go that far, but they packed and repacked the court. They added a tenth justice (in 1863), squeezed the number down to seven members (in 1866) and, finally, returned it to nine (in 1869). The Republicans also reached into the lower courts and rearranged the Circuits. The partisan reorganization of the courts –the only sustained court packing in American history-- went on for most of a decade.

The lessons from Dred Scott echo down through to the present day. A declining political party only injured itself by using the courts to settle a fierce political controversy. Even more important, the Court’s plunge into the hottest issue of the era blew right back on the Court itself. Taney’s botched effort to settle the slavery issue sends a warning to every generation. There are distinct limits to the Court’s legitimacy in highly partisan times. Modest jurisprudence can protect the court. Overreach can cause all kinds of blowback.

This essay is taken from Republic of Wrath: How American Politics Turned Tribal from George Washington to Donald Trump (Basic Books, September 2020)