The Birth, and Life, of a Word

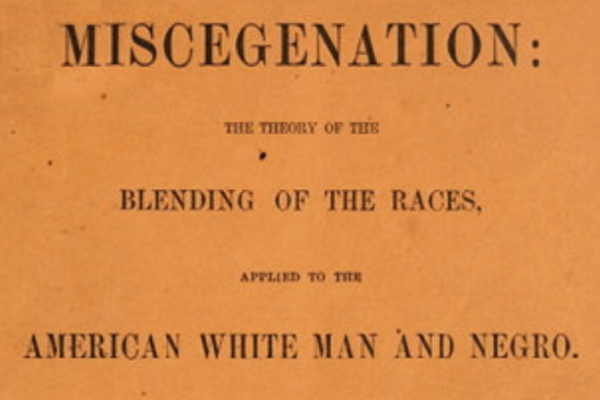

During the presidential campaign of 1864, a seventy-two-page booklet appeared on the streets of Manhattan. This publication was titled Miscegenation: The Theory of the Blending of the Races, Applied to the American White Man and Negro. It cost 25 cents. According to the booklet’s anonymous author, “miscegenation” was a word he’d created by combining the Latin root words miscere (to mix) and genus (race). This, the pamphleteer explained, was a more scientific term than “amalgamation,” which he considered a “poor word” to describe white-black intermarriage.

The author then expounded at length about the virtues of miscegenation that would inevitably follow a Union victory in the Civil War. “The miscegenetic or mixed races are much superior mentally, physically, and morally to those pure or unmixed,” he wrote. For this reason, “it is desirable that the white man should marry the black woman and the white woman the black man...” When Asians and Indians were added to the mix, he continued, the result would be an improved race of “miscegens.”

This position may not sound preposterous in today’s multicultural world, but in the racially charged atmosphere of Civil War–era America, it was incendiary. The idea that intermarriage would be not only an inevitable, but a desirable, consequence of emancipation was a radical and—in the north and south alike—disturbing prospect. Yet this was exactly what Miscegenation proposed.

To increase the impact of his booklet, its author sent copies to a number of prominent Americans. The one that went to Abraham Lincoln was accompanied by a note extolling “human brotherhood.” This message expressed hope that the president would stand four-square for equality between “the white and colored laborer,” an inflammatory suggestion in working-class neighborhoods of racially and ethnically polarized cities such as New York. Although Lincoln did not endorse Miscegenation, some abolitionists who received copies did. A few anti-slavery publications, including the Anglo-African Review and the National Anti- Slavery Standard, reviewed it favorably.

The contents of Miscegenation quickly became a focal point of campaign oratory. As the 1864 election approached, talk of “miscegenation” dominated America’s political discourse. In Washington, D.C., a Polish expat wrote in his diary, “The question of the crossing of races, or as the newly-invented sacramental word says, of miscegenation, agitates the press and some would be savants in Congress.” Slavery-tolerant Democrats used this neologism to bludgeon antislavery Republicans who, they said, were hell-bent on mongrelizing the white race. Democratic publications warned that race-mixing would be the logical consequence of Abraham Lincoln’s “Miscegenation Proclamation.” The Cincinnati Enquirer advised its readers to beware of “zealous miscegenators.” A Democratic newspaper in New Hampshire ran a widely reprinted article headlined “Sixty-Four Miscegenation,” which claimed, falsely, that sixty-four abolitionist schoolteachers in New England had given birth to mixed-race babies. On the other side of the debate, humorist David Ross Locke, a staunch Republican and favorite of President Lincoln, incorporated the new word into his portrayal of a clueless, semiliterate Confederate named Petroleum Vesuvius Nasby. “Lern to spell and pronownce Missenegenegenashun,” Nasby/ Locke advised. “It’s a good word.”

But not one that was genuine. Miscegenation turned out to be the creation of two New York journalists who weren’t advocates of race-mixing at all. Their booklet was a hoax: a political dirty trick meant to sabotage Republican prospects in the election of 1864. Years after Miscegenation was published, its authors were unmasked as David Goodman Croly and George Wakeman of New York’s Democratic newspaper The World. By coining this word and using it as the title of their provocative booklet, Wakeman and Croly hoped they could undermine Republican candidates by making the controversial issue of intermarriage a focal point of political discourse.

Without naming its perpetrators, a World article headlined the “Miscegenation Hoax” that appeared two weeks after Lincoln’s 1865 inauguration, expressed horror at the way avid abolitionists had overlooked “the barbaric character of the compound word ‘miscegenation.’” This article predicted that “the name will doubtless die out by virtue of its inherent malformation. We have bastard and hump-backed words enough already in our verbal army corps.” In fact, the World concluded, as a usable word, miscegenation had already “passed into history.”

Although the uproar surrounding “miscegenation” did die down after Lincoln’s reelection, the word itself did not. By now it’s a well-established part of our lexicon. In a sort of professional hat tip, the renowned hoaxer (and Republican stalwart) P. T. Barnum devoted an entire chapter of his 1866 book The Humbugs of the World to detailing the shrewd composition and brilliant rollout of Miscegenation. The successful propagation of this mock neologism was due to “one of the most impudent as well as ingenious literary hoaxes of the present day,” wrote Barnum. Even though it wasn’t meant to be taken seriously, or outlive its devious intent, miscegenation caught on and stuck around. Following the Emancipation Proclamation, such a scientific-sounding term was needed to help us navigate the controversial topic of intermarriage. In the absence of anything better, miscegenation fit that bill. To this very day, that word is used so commonly for racially mixed relationships that it doesn’t even elicit synonyms in an online thesaurus. It has even spawned a verb. As literary scholar Walter Redfern once wrote, “The urge to miscegenate counteracts racism.”

David Croly had mixed feelings about his role in coauthoring a word that became so ubiquitous. Long after he died, Croly’s widow recalled the way miscegenation was conceived as her husband and a colleague (George Wakeman) composed their tract by that title. “I remember the episode perfectly, and the half joking, half earnest spirit in which the pamphlet was written,” she said. Be that as it may, Mrs. Croly concluded, her husband’s coinage “added a new, distinctive, and needed word to the vocabulary.” One American who didn’t agree was David Croly himself. Croly considered amalgamation a perfectly good term, one he used until his death in 1889.