The Women Who Fought Tooth and Nail for the Flint Sit-Down Strikes

A Women's Brigade picketer breaks a window after police tear gassed the occupied Chevrolet Plant 9 during the Flint sit-down strikes.

Still from With Babies and Banners: Story of the Women's Emergency Brigade, Women's Labor History Film Project, 1978.

In downtown Flint, Mich., stands a pantheon of statues dedicated to automotive pioneers. David Buick and Louis Chevrolet, the namesakes of two of General Motors’ classic brands, are both world famous. Some Flintstones would like to add a statue of a lesser-known figure: Genora Johnson, leader of the Women’s Emergency Brigade during the 1936-37 Flint Sit Down Strike.

The strike began on December 30, 1936, when autoworkers occupied GM’s Fisher One plant, demanding better wages, more job security, and an end to the hated assembly line “speed up,” which so exhausted the workers that they could barely pick up a fork to eat at the end of the shift. That night, the “cut and sew” women in the upholstery department were ordered to leave the plant, to deter rumors of sexual mingling among strikers.

When Genora Johnson first offered to volunteer at strike headquarters, in Flint’s Pengelly Building, she was assigned to the kitchen, like all the other members of the Ladies’ Auxiliary. Johnson, a striker’s wife long devoted to socialist causes, thought women belonged on the front lines of the strike, beside their husbands, brothers, fathers and sons. First, she organized a picket line outside Fisher One. Her two-year-old son held a placard reading “My Daddy Strikes for Us Little Tykes.”

From With Babies and Banners

On February 11, 1937, the Flint police attacked Fisher Two, in what became known as the Battle of the Running Bulls. The strikers repelled the police by pelting them with door hinges and spraying them with fire hoses. During their retreat, the police opened fire, wounding 14 unionists. After the shooting stopped, Johnson urged a group of women to break through the police lines, and protect the men inside the plant from further violence.

“I ask all the women here tonight to come down and stand with your husbands and brothers,” she declared through a loudspeaker mounted on a sound car. “If the police are cowards enough to shoot down defenseless men, they’re cowards enough to shoot down women. Women of the city of Flint, break through these police lines, and come down here and stand with your husbands and your brothers, your sons and your sweethearts.”

The Battle of the Running Bulls transformed the Ladies’ Auxiliary from a homemakers’ sodality to a quasi-military force. After the women formed a human shield outside Fisher Two, they realized they were just as courageous as the men, and just as capable of standing up to the police—maybe more so, because the “flatfeet,” as they call the cops, wouldn’t attack women.

“We have got to organize the women,” Johnson declared that night. “We have got to have a military formation of the women. If the cops start firing into the men, the women can take the front line ranks. Let them dare to shoot women!”

The next day, fifty mothers, daughters, wives, and sisters gathered at the Pengelly Building, in answer to Johnson’s call for women willing to place their bodies between police and strikers. “It can’t be somebody who’s weak of heart!” she announced. “You can’t get hysterical if your sister beside you drops down on a pool of blood. We can’t be bothered with having to take care of two people, if one is injured and another is going to go hysterical. Do not sign up for the Women’s Brigade, take your role in the strike kitchen, take your role in the first aid station in the Ladies’ Auxiliary.”

The first to stand was a woman in her seventies.

“This is going to be difficult for you,” Johnson cautioned.

“You can’t keep me out,” the old woman insisted. “My sons work in that factory. My husband worked in that factory before he died, and I have grandsons there.”

Of the thousand women who belonged to the Ladies’ Auxiliary, four hundred joined the Women’s Emergency Brigade. Every member was issued a red beret and red armband with the white letters “E. B.” Johnson appointed herself captain. Tall, with raw-boned features, a deep background in labor rhetoric, and a commanding manner, she was a natural leader. Her five lieutenants each commanded a squadron ready to gather outside a factory at the summons of a phone call.

The women adopted a military-style costume of jodhpurs, a waist-length jacket, and knee-high boots. And they armed themselves. From the men inside Fisher One, one woman acquired a blackjack, attaching it to a wristlet concealed inside her sleeve so she could flick it out at the first sign of trouble. All the women in the Brigade carried billy clubs, their handles whittled down to fit a female grip.

Women's Emergency Brigade picketer smashes a window at Chevrolet Plant 9. From With Babies and Banners.

The Brigade got its first taste of battle when the strikers attempted to capture and occupy two Chevrolet engine plants. At Chevy Nine, plant police resisted the takeover by firing tear gas at workers inside the plant. As the close air of the shop floor filled with the choking smoke, a striker broke a window. Pushing his bloodied face through the hole in the glass, he shouted to the women on the sidewalk, “They are gassing us! They are gassing us!”

“Smash the windows!” ordered a voice from the union sound car.

Dressed for battle in red berets and armbands, parading with an American flag at the head of their column, thirty Brigade members pulled billy clubs out from under their long winter coats and swung them at the bank of windows.

“They’re gassing our husbands!” one woman yelled. “Give them air!”

The women shattered every pane they could reach, littering the shop floor with tinkling shards of glass. Tear gas flowed out through the jagged holes. When the Flint police attempted to arrest a club-wielding Brigade member, she wriggled in their grasp, shrieking “Get your hands off me!”

From With Babies and Banners

(The next day’s New York Times reported their action under the headline “Women’s Brigade Uses Heavy Clubs.” The Flint Journal wrote, “These women smashed scores of windows in the plant in a hysterical frenzy, seemingly with an urge to destroy, for officials could find no other reason for smashing glass in window after window.”)

After the strikers captured Chevy Four, the Brigade formed a barricade around the plant.

“What kind of cowards hide behind women?” a cop bellowed, loudly enough so the men inside the plant could hear.

Johnson took this taunt personally. Climbing into the sound car, she grabbed the microphone to denounce the company’s “hired thugs.”

“We don’t want any violence,” she declared. “We don’t want any trouble. My husband is one of the Sit Down Strikers. We are going to fight to protect our men.”

From With Babies and Banners

The strikers occupied GM’s plants for 44 days before the company capitulated, allowing the United Auto Workers to negotiate on their behalf. The strike guaranteed middle class wages and benefits for autoworkers for generations to come.

Wearing the red beret of the Women's Emergency Brigade, Genora Johnson Dollinger addresses the UAW in 1977, using the occasion of the fortieth anniversary of the Flint strikes to demand the union include issues like child care in contract negotiations. From With Babies and Banners.

At the Sit-Downers Memorial Park, outside UAW Region 1-D in Flint, there is a bronze statue of an anonymous Women’s Emergency Brigade member smashing a window with a billy club. On White Shirt Day, held every February 11 in Flint to commemorate the strike’s end, women dressed in red berets and armbands serve bean soup, bread and apples, food the Sit Downers ate in the plants. Genora Johnson, though, has never been memorialized. A downtown statue of Flint’s Spartan woman would honor not only her, but all the women who played a role in winning the Sit-Down Strike.

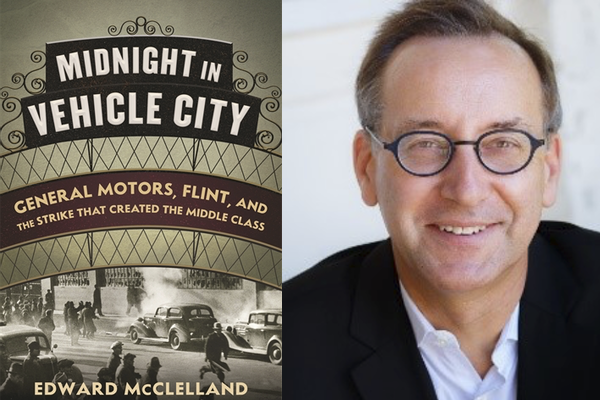

Excerpted from Midnight in Vehicle City: General Motors, Flint, and the Strike That Created the Middle Class by Edward McClelland. Copyright 2021. Excerpted with Permission from Beacon Press.