Can Space Exploration Restore American Faith in Science?

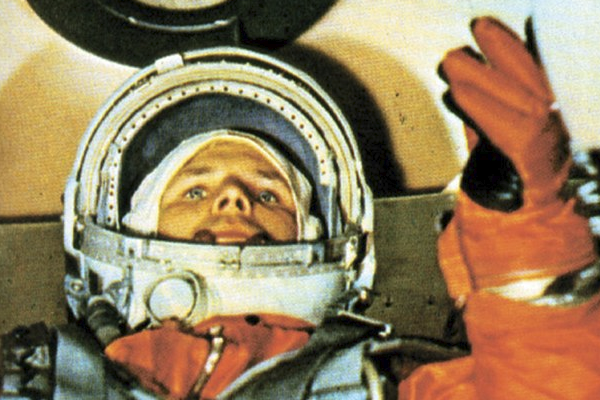

Yuri Gagarin prepares for the first manned space flight, April 12, 1961

April 12 marks both the 60th anniversary of the first manned space flight and the 40th anniversary of the first U.S. space shuttle launch. These anniversaries might pass with little fanfare, but as NASA hopes to put the first woman on the moon by 2024 with its Artemis mission, Americans might want to ask themselves how so much of the wonder of space exploration has faded in just six decades — and faith in science and our institutions with it.

On so many levels, the era that produced American space travel will seem like a foreign country, even to those who once lived there. This was a time when massive expenditures by the government for new projects and bureaucracies were not only unremarkable but exciting. It was a time when the public sector and the private sector were not only tightly enmeshed, but it was the public sector and the guiding hand of the government that was dominant and no one thought to call it socialism. It was a time when we implicitly trusted our government.

The space program was a symbol of our incredible faith in both our government and science. The scourge of polio had just been conquered as Sputnik brought new fear into our lives, and our faith in the government and scientists to protect us was natural. Americans would breathlessly listen to reports from an American scientist with an incredibly thick German accent and a name that suggests he was a recent immigrant, Wernher von Braun. His rehabilitation from Nazi to German-American was a simple matter of suspending our disbelief, which was easy because we had faith in our institutions. Whether it was curing polio or conquering space, Americans believed that men in white coats would point the way to a better future. Even with the breathtaking progress of research into the pandemic, American faith in science is far from its halcyon 1950s/1960s high.

The Challenger tragedy shattered our dreams, but more than three decades later, there are few signs America is ready to once more trust or even take seriously the science of space flight.

Today, we do not have the patience to follow the advice of scientists in the face of the greatest health crisis America has ever faced. We do not have the political will to make investments that will pay off in the future. So how will we be able to delay our gratification to make the kind of wise, patient investment that the space program needs? John F. Kennedy made a promise in 1962 that NASA kept in 1969, just under the wire. What promises will Americans make to our future selves?

I would guess that a lot of Americans, if asked to think of the future of space travel, would think of Elon Musk, and just maybe Virgin Galactic — both of these have a certain futuristic flair to them and a lot of profit motive. The incredible image of the earth in space, the “big blue marble” taken on December 7, 1972, briefly united a world divided by Cold War and hot wars, a world haunted by the prospect of impending famine and disease. That image reminded us that we were all united after all. That sight could soon be available to the highest bidders as a selfie background. It remains to be seen if a celebrity influencer could have the same gravitas as an astronaut. It won’t be easy to remind us of our shared humanity and the miracle of science.

Space tourism and space hotels, a space entrepreneur who seems part Tony Stark, part P.T. Barnum — this is what Americans think of the future of space. While the private sector focuses on such frivolity as sending a Tesla to space, the scientists, mathematicians and engineers trudge on, mapping the trajectories and designing the spacecraft and software, and waiting for the stars to align themselves again. The astronauts train, dreaming of the chance to go up.

Our rocket scientists are some of the most brilliant people in the world. Instead of getting rich — and please notice the parking lots of their workplaces are not filled with luxury cars — they are using their brilliance to take mankind further than it had gone before. And the astronauts? They are part rocket scientist, part superhero. The best of the best in so many physical, mental, and emotional categories. They risk their lives for the dream of exploration. They used to be household names and international heroes. Maybe they can be again.