Popular Histories Have Influenced World Leaders, Sometimes For the Better

Sometimes presidents are influenced by history books. Bill Clinton consulted Balkan Ghosts: A Journey Through History by Robert Kaplan when dealing with conflicts in southeastern Europe. In 2008 Barack Obama consulted Jonathan Alter’s The Defining Moment: FDR’s Hundred Days and the Triumph of Hope for ideas about launching a strong presidency. Joe Biden liked The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels so much that he made its author, Jon Meacham, a key adviser. No historian, however, has made a more significant impact on an American president’s thoughts and actions than Barbara Tuchman. President John F. Kennedy drew important lessons from one of her books when seeking a peaceful resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

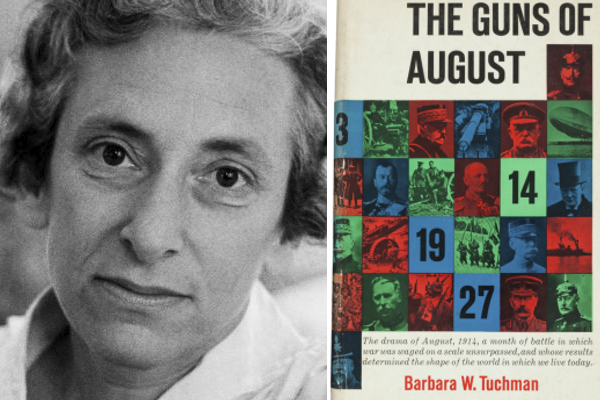

Who was this woman whose writing about history may have influenced the course of history in significant ways?

Barbara Tuchman became one of the most-read historians of the 1960s and 1970s. Her parents were distinguished financiers, public servants, and philanthropists. Tuchman was related to Henry Morgenthau, Sr., Woodrow Wilson’s ambassador to the Ottoman Empire and Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Franklin D. Roosevelt’s secretary of the treasury. Barbara Tuchman traveled and lived in Europe and Asia during her formative years. She published a book about British policy toward Spain in 1938, but parenting responsibilities kept her away from writing book-length historical interpretations until 1956, when she released Bible and Sword. Several best-sellers followed.

Some academic historians criticized Tuchman’s “popular” histories for amateurism and superficiality. She defended her approach, pointing out that many scholars fail to tell a good story. Tuchman asserted “you have to be clear and you have to be interesting” when writing for the public. A historian always needs to ask, “Will the reader turn the page?”

In one of her most influential books, The March of Folly: From Troy to Vietnam (1984), Barbara Tuchman delivered strongly opinionated judgments about foolish decisions by powerful figures in history. She observed, for example, that aggressive actions by popes of the Renaissance provoked the Protestant Reformation, and King George III’s inept handling of protests by colonists provoked the American Revolution. The longest chapter in her book dealt with the “folly” of U.S. military intervention in Vietnam.

Tuchman referred often to the “wooden-headedness” of leaders – their tendency to make decisions guided by preconceived notions. Many of the leaders she studied ignored or rejected recommendations to consider different courses of action. Tuchman did not view historical outcomes as inevitable. She believed many situations could have turned out differently – and for the better – if leaders examined their options seriously and considered the long-term consequences of their decisions.

That idea was a principal theme in The Guns of August, published in 1962, which made a profound impression on President John F. Kennedy. Tuchman’s book dealt with the first month of World War I, when European nations plunged into war. Fighting did not end quickly, as national leaders expected. The conflict severely damaged European civilization and created devastation in other regions. Twenty million people died. There were long-term repercussions, as well. During the war, a communist revolution succeeded in Russia. Later the Nazis became dominant in Germany. A Second World War and a long Cold War followed. Numerous problems of the twentieth century could be traced to leaders’ mistaken judgments in August 1914.

President John F. Kennedy read The Guns of August shortly before the Cuban Missile Crisis began, and he referred to the book often during the crisis. When U.S. reconnaissance photos showed the Soviets were erecting missile bases in Cuba, Kennedy convened secret meetings to discuss responses. General Curtis LeMay and other military officers wanted to bomb the missile sites. They believed a massive display of U.S. power would force the Soviets to capitulate. President Kennedy was not convinced. Recalling lessons from Tuchman’s book, he recognized that generals frequently call for strikes during international crises. Once combat begins, political leaders come under enormous pressure to continue the clash of arms until victory is achieved.

During tense discussions in October 1962, President Kennedy recalled a conversation reported in Tuchman’s book in which a former German chancellor expressed puzzlement about the war’s outbreak in August 1914. “How did it all happen?” he asked. His successor responded, “Ah, if only one knew.” Kennedy, thinking of the missile crisis, exclaimed, “If this planet is ever ravaged by nuclear war – if the survivors of that destruction can then endure the fire, poison, chaos and catastrophe – I do not want one of these survivors to ask another, ‘How did it all happen” and to receive the incredible reply: ‘Ah, if only one knew.’” Kennedy declared “I am not going to follow a course which will allow anyone to write a comparable book about this time [called] The Missiles of October. If anybody is around to write after this, they are going to understand that we made every effort to find peace and every effort to give our adversary room to move.”

President Kennedy wanted others to profit from the perspective he gained from The Guns of August. He asked top aides to read the book. Kennedy wanted to send a copy to every Navy officer, but he acknowledged they probably would not read it.

Rather than plunge into war, Kennedy and officials in his administration arranged a “quarantine” of waters around Cuba. Eventually, they secured a peaceful resolution of the crisis. As many historians have since noted, the world was on the brink of a nuclear catastrophe in October 1962. Fortunately, leaders in Washington and Moscow pulled away from it.

Barbara Tuchman was not an enthusiast of war-making, and that attitude was evident in much of her writing. Reviewing the record of mankind’s numerous failures to resolve conflicts peacefully, she reminded readers that feasible alternatives to war are often available. Unfortunately, leaders sometimes fail to explore those opportunities earnestly.

In the 1980s journalist Bill Moyers conducted an interview with Tuchman. Moyers suggested the American people had, at last, come to recognize the futility of many armed conflicts. “I think in our collective wisdom the American people did learn from the Vietnam experience,” Moyers observed. They learned “not to let another president take us into a war unless he can present overwhelming evidence that our national security was clearly at stake.” Then Moyers asked, “Don’t you find that encouraging?”

Tuchman expressed hope that Americans had absorbed lessons from their country’s experience in Vietnam, but she pointed out that leaders “persist in folly because they don’t want to let go of their position, of their power, and they are afraid that if they let go and if they say ‘we were wrong, or we’re doing the wrong thing’ they will be booted out or they will lose their status.”

Years after Barbara Tuchman’s death in 1989, those words seemed prophetic. In 2003 President George W. Bush and top officials in his administration created a rationale for war based on flimsy evidence. When weapons of mass destruction did not turn up in Iraq and there was no compelling evidence of Saddam Hussein’s connections to the 9/11 attacks, they refused to say, “we were wrong.” If Tuchman had been alive at the time, she would likely cite the invasion of Iraq as another example of “folly” and remind Americans that President John F. Kennedy, an avid reader of history, asked tough questions and made informed decisions when dealing with an international crisis.