A Writer Reflects on Four Enlightening and Challenging Lunches with the Father of Black Liberation Theology

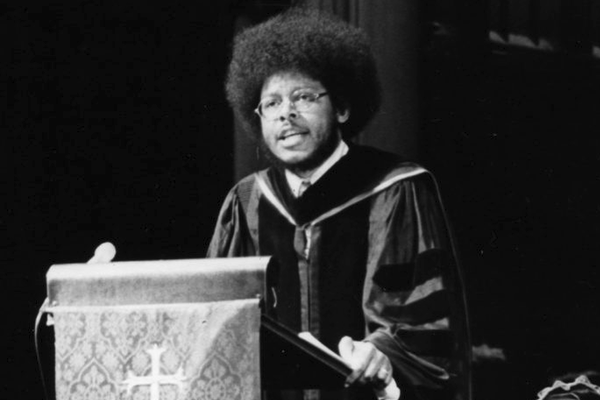

Dr. James H. Cone, Union Theological Seminary, 1969

The summer of 2013 proved especially consequential for me, occasioned by a series of four private lunches with Dr. James H. Cone, author of Black Theology & Black Power, a book that has, since its release, carried the distinction as “the founding text of Black liberation theology.” To Cone, long-time distinguished professor at Union Theological Seminary, the gospel of Christianity had been hijacked and distorted by “white, Euro-American values.”

I have come to realize the conversations I experienced that summer with Cone – just the two of us, Black and white, one on one – constituted an essential segment of my “white reckoning,” a moment in time when my racial past, impressions, and ideas came under forceful examination by a newfound and sophisticated friend, whose distant Arkansas background and my own were similar, although we viewed the subjects we explored from historically obverse realities. After all, the two of us spent our youths – I was the younger – in small towns in south Arkansas around the same time with only six years in age and a relatively short distance of fifty miles separating us.

The thoughts rushed unbridled and unmeasured into consciousness as my wife, Freda, and I sat at the funeral for Cone on Monday, May 7, 2018, nearly five years after the intense discussions he and I shared over that summer of 2013. Seating capacity at Riverside Church on the upper west side of Manhattan is just a little over 2,000. From the vantage point of the pew we occupied that day, Riverside Church overflowed with a scattering of whites amid an ocean of African-Americans. Listening to nearby conversations, I realized many attendees traveled long distances to arrive at the ceremony honoring this controversial but seminal figure of philosophical and theological importance. As the funeral progressed, I felt a thrill about the degree of respect and acceptance his Black liberation theology had obviously gained among Black people across the country.

Thrilled. I cannot think of a better word to express my response to the crowd’s puissant reaction to Cone’s views of Black life in the United States. Eulogies were plentiful that day from prominent leaders in America’s Black churches and liberation theological circles, such as Cone’s friend Dr. Cornel West, former student Raphael Warnock (then the senior minister at Martin Luther King’s Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, who would later, in 2021, be elected Georgia’s first African-American United States Senator), and Dr. Kelly Brown Douglas, Cone protégé, prominent author, and Dean of the Episcopal Divinity School at Union Theological Seminary.

At least for this white author, my prospective book cried out for the voice of James Cone. While I had the advantage of a first-hand racial reckoning with him asking questions and probing many answers, Cone’s writings called whites to task for their beliefs and behavior toward Blacks and Black liberation. In many ways like Malcolm X, his voice would be unheard at the nation’s peril.

My long 2013 article on the Elaine Race Massacre had been published in a national literary periodical, a copy of which I provided to Cone, who wanted to know more about the Elaine conflagration than my piece conveyed. He and I inherited common knowledge about the region where the massacre happened and the associated racial rituals, practices, and oppression that occurred there. We each recognized that so much about the Massacre was not unique for south Arkansas – only a matter of the slightest degree separated in 1919 a mass murder of African-Americans from a single lynching.

A geographic commonality brought us together, as he had shown considerable interest to learn much more about the Elaine Race Massacre, leading to our first luncheon in mid-June; the lunches spread over the summer, ending in late August. I was familiar with Cone’s work, having read some of his theological writings. He knew little of me but for my authorship of the Massacre piece and biographical highlights that accompanied it, unless he looked for more elsewhere.

James Hal Cone had been born August 5, 1938 in Fordyce, Arkansas, then a town of about 3,400 persons a little over forty miles northwest from my hometown of Monticello via a two-lane road – much of it would have been unpaved at that time. Eighty years ago, these two communities were about the same size. Located in the timberlands of rural south Arkansas, Fordyce’s only claim to fame during the 20th century rested on the municipality being the hometown of Paul “Bear” Bryant, legendary football coach for the University of Alabama Crimson Tide. Actually, Cone spent his youth in the smaller community of Bearden, some fourteen miles southwest of Fordyce and hosting a population of less than 1,000.

During the course of the 2013 summer, he recited for me a variety of stories about growing up in aggressively segregated south Arkansas and, more particularly, in Bearden. One such story dealt with watching a Black man being pistol whipped in town at a four-way crossing by a local white law enforcement officer; apparently, the policeman thought he had been too slow in accelerating his vehicle. Such gratuitous and arbitrary acts of violence, affront, and unfairness perpetrated by whites in and around Bearden wore on Cone for the rest of life. He often invoked his parents’ relevance and influence, sometimes summoning his father’s name, “Charlie,” seemingly to give Cone supplementary insights and additional fortitude to confront a moment of dilemma, uncertainty, or past pain.

From the outset, Cone brought to each of our lunches, as a gift, a different, personally inscribed book he had written, and from the very beginning of our conversations, I was struck by the eagerness, curiosity, and transparency of this man in his mid-70s. Throughout the summer, stories of Cone’s life in Arkansas, including the years he spent in Little Rock studying at Shorter College and Philander Smith College before moving on to receive his doctorate from Northwestern University, would stream from him unencumbered. While a student in Arkansas, he held a job as chauffeur for a prominent Little Rock businessman, with the “n-word” freely employed by his employer’s associates and colleagues from the backseat of the automobile. Recounting these stories of being a chauffeur, Cone still remained incensed at the ignominy of having to don the obligatory driver’s cap as part of his job.

Cone showed insistence at learning as much as possible about me: What was it like being white and teaching in the all African-American school in Monticello before integration, and what was the response then to my efforts from the local communities, both Black and white? How did my family react to my views and actions? How did I come to read much Dietrich Bonhoeffer? How did my views about race develop to differ so tellingly from whites in south Arkansas, particularly from my own family? What did I think of James Baldwin and Malcolm X? Did the Episcopal Church make any reparations in connection with its apology and national day of repentance for the Church’s role in transatlantic slavery, using a litany which I wrote at the Church’s request? How and why did I become so committed to the first physical memorial to the Elaine Race Massacre? Conducting a deluge of weighty, but sometimes intimidating questions, he was continuously and implacably inquisitive, this renowned professor at prestigious Union Theological Seminary, where he had taught since 1969, this man of profound humility, who, notwithstanding his enviable oeuvre of remarkable compositions, complained about his writing skills and the great difficulty he faced putting word after word on paper.

He freely described and discussed the myriad of crucial subjects that occupied his focus and ruminations, including the steps and circumstances that brought him to Black liberation theology; his regular criticism of Reinhold Niebuhr’s neglect of Black plight in Detroit and New York City, two cities where Niebuhr had been quite active; our mutual attention to the Detroit riots, the City of Detroit, and surrounding Wayne County, Michigan (two local governments I served as a consultant earlier in my life and career); his belief that Black people habitually hide their more visceral comments about white people; the Million Man March; his view that white subjugation of African-Americans thrusts a higher burden of original sin on white folks; and our mutual recall of the integration of Little Rock Central High School, which happened in 1957 as I became a teenager and Cone was nineteen years old.

Our final lunch in late August, 2013 proved to be the least satisfying – for us both, I believe. The conversation started very uncharacteristically with personal recriminations by Cone. He accused me, citing verbally an identical shortcoming for all whites, of not paying enough attention to Malcolm X. He additionally upbraided me, referencing and castigating whites as a group generally, for not understanding Black circumstances and attitudes. Shortly into this unexpected jeremiad, I received a telephone call notifying me that my wife unpredictably needed to go to the hospital, and I should meet her there as soon as possible. Cone’s demeanor shifted instantly and dramatically, demonstrating much concern and sympathy, but I needed to dash. So, our relationship ended quite abruptly and unsatisfactorily. He exhibited irritation with me for reasons that are still baffling, and I, in turn, felt offended at his aggression. We never reached out to each other again.

As a result of these summertime lunches with Dr. James H. Cone, I have often pondered and attempted to answer the conundrum I have never been fully able to answer – that is, why did he desire to continue many lengthy discussions with me? We never really had a detailed agenda for any one of our talks. Until the very end, each of our meetings carried the redolent purpose of friends meeting for no reason other than to share notable experiences and personal propositions. After thinking about this question for years, I have resolved that I probably represented an opportunity for Cone to enter into a previously unrealized conversation he envisioned with a white person from his past who would willingly acknowledge and comprehend the life in Bearden and south Arkansas that Cone endured and overcame from the 1940s and 1950s. Is it wrong of me to surmise that four summer lunches in 2013 created a retrospective for James Cone that brought his own history and views into clearer focus against a backdrop of passage with a white man?