Are the Modern Stoics Really Epicureans?

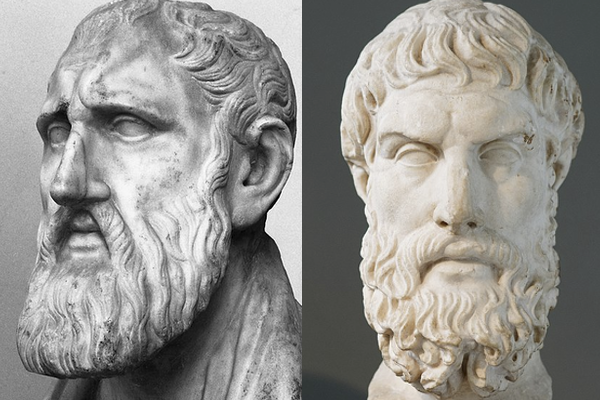

Zeno of Citium (c. 335-c.263 BCE) and Epicurus (341-270 BCE)

Modern Stoicism has saturated the philosophical market—seminars, apps, podcasts, retreats, bestseller lists, psychotherapy. As a specialist in ancient Greek philosophy, I admit that I’m pleased to see so many people take an interest in what I study for a living. Stoicism has a lot going for it, and many of my students are powerfully drawn to its core commitments. All that is to say, I can see the allure.

My aim here, though, is to convince readers, especially those committed to evolutionary science and modern physics, to learn more about Epicureanism, Stoicism’s oldest and greatest rival. Cards on the table—I prefer Epicureanism, and I have recently published a book on Epicureanism as a way of life. That said, I think even devoted, forever members of the Stoic caucus have good reason to study Epicureanism, if only because taking your rivals seriously is a sign of intellectual virtue, an indication that you have not grown complacent. As a more controversial point, I suspect that many Modern Stoics are already Epicureans, at least by the standards of the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius. Let me explain.

The Epicureans and Stoics were at loggerheads from their very beginnings. Epicurus (341-270 B.C.E) and Zeno of Citium (c. 335-c. 263 B.C.E), Stoicism’s founder, were fellow residents of Athens, and their schools developed in response to the same set of political and material circumstances. Specifically, Athens was a city in decline. It found itself knocked down a peg after many years of power and democratic self-rule, the city having been conquered by the Macedonians, their fellow Greeks to the north. Athens had lost control of its major port, the Piraeus, the gateway to their once abundant wealth. The region suffered periodic military incursions and occasional food shortages. Many scholars (though not all) think this precarious environment explains why Greek philosophy during the Hellenistic Era seems to give greater attention to developing resilience in circumstances of scarcity, discord, and powerlessness.

Both Stoicism and Epicureanism, then, were designed to help followers manage periods of uncertainty and adversity, and in that respect they both perform commendably. Notable Stoics even tended to praise Epicureanism in this respect. The Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, who identified himself as a Stoic, admired Epicurus the man, especially his moderation, his tolerance of pain, and his noble death: “In sickness, then, if you are sick, or in trouble of any other kind, be like Epicurus.” Seneca, also a Roman Stoic, likewise praised Epicurus’ self-control. It makes sense that Marcus and Seneca would respect many features of Epicureanism. Both Stoicism and Epicureanism teach the importance of using reason to control our desires, that misfortune need not put happiness out of reach, and that an important part of living well is preparing to die well. They both suggest ways to preserve joy when things go south.

So what sets Epicureanism and Stoicism apart? One way to get at the answer is to consider why Marcus himself opposed Epicureanism. In short, Marcus objected to Epicurus’ natural science and his advocacy of hedonism, the view that humans achieve tranquility through strategic pursuit of pleasure and avoidance of pain. That sounds like two objections—natural science and hedonism—but it’s really one. The Epicureans were intellectually-refined hedonists because of their science.

The most striking feature of Epicurean natural science is how much they got right. Epicurus thought the cosmos in its entirety is composed of atoms and void. The atoms collide, come together, and break apart according to fixed causal principles with some occasional indeterminacy of the sort postulated in particle physics. The opening quote of Neil de Grasse Tyson’s Astrophysics for People in a Hurry comes from the Roman poet Lucretius, whose account of Epicurean atomism inspired major figures in the Scientific Revolution.

The Epicureans were also, thousands of years before Darwin, proponents of an evolutionary account of the origin of the species. They thought the species that populate our earth are the ones that have proven the fittest in a fight for survival. On a general evolutionary account, animals seek pleasure and avoid pain by nature (i.e., they are hedonists). Humans distinguish themselves from other animals by our powers of reason and sense of ourselves in time, which allows us to deliberate about what will most effectively produce pleasure and minimize pain over the long-term. We are animals with a souped-up practical reason.

Marcus rejected these Epicurean views whole-heartedly because he considered the divine creation of a providential universe essential to the Stoic project, as did other Roman Stoics like Epictetus and their Greek predecessors. For the Stoics, human rationality is a manifestation of God’s generosity to humans, not a sophisticated animal capacity. Marcus insists that “the whole divine economy is pervaded by Providence.” When he writes, “If not a wise Providence, then a jumble of atoms,” he means to offer two options: “If not Stoicism, then Epicureanism.” In fact, Marcus admits that if Epicurean natural science were right, he would fall into despair. Without providence, he asks, “Why care about anything?”

I have good friends, students, and close relatives who fall on opposing sides of the providential creation divide, and I understand that people have their own reasons for choosing one commitment over the other. Modern Stoics, though, cannot simply set aside the fact that the Stoics fell squarely on the side of providence without risk of undermining some of Stoicism’s core tenets. Stoicism’s emblematic acceptance of suffering follows from their ability to reconceive it as divine providence, as God working in “mysterious ways.” Marcus writes that someone who suffers something “unpalatable” should “nevertheless always receive it gladly” because Zeus designed individual suffering “for the benefit of the whole.” Even Stoicism’s deep, admirable commitment to caring for all humankind, the notion that we are all “citizens of the cosmos,” is fundamentally grounded in the view that all human beings are manifestations of God.

Epicureans, by contrast, build their practical philosophy on a natural science that denies a cosmic significance to suffering, and they see their endorsement of hedonism as an outgrowth of treating humans as sophisticated animals rather than as expressions of a divine rational nature. Epicurus was not an atheist, but he denied a providential God who created the universe or intervenes in its events. Perhaps, then, many Modern Stoics should consider reading more about Epicureanism, since Marcus admired Epicurus’ resilience, temperance, and approach to death, which all grew out of a science many Modern Stoics already accept (and that the Stoics vehemently opposed).