Christopher Gorham Gives the Remarkable Anna Marie Rosenberg the Bio She Deserves

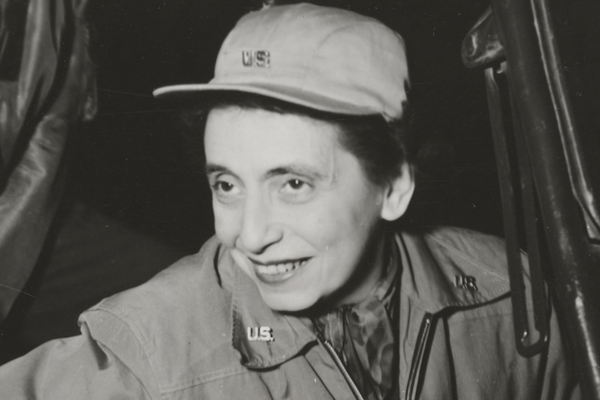

Anna Marie Rosenberg, photographed while touring Korea as an Assistant Secretary of Defense in the Truman administration

The Confidante by Christopher C. Gorham (Kensington Books)

Anna Marie Rosenberg was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish immigrant who was known as “the busiest woman in New York” and “Seven-Job Anna” due to demand for her expertise in public relations and the then-new field of labor negotiations. She was so close to New York’s Republican mayor Fiorello La Guardia that he picked her up in his limousine each morning and dropped her off at her office before continuing to City Hall.

Major corporations hired Rosenberg to settle their labor problems in the strike-prone 1920s and 1930s. “Settling a strike or striking a deal, Anna would command, ‘Pipe down, boys, and listen to me.’ Whether union or management, she would tell them not what they wanted to hear, but what they needed to hear,” writes Christopher C. Gorham, author of the absorbing new biography The Confidante: The Untold Story of the Woman Who Helped Win World War II and Shape Modern America. “The deal done, she would clap her hands together, bracelets jangling, and congratulate the parties, ‘Wunnerful job, gentlemen!’”

Rosenberg first encountered Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt when he ran for governor of New York in 1928. She joined the campaign as a labor advisor and continued to be an important member of his political circle until his death in 1945. Her influence on presidents continued for another twenty years. According to Gorham, “Anna’s combination of skill and social ease was valued by FDR as he won the presidency, and by her thirties she was the nation’s only woman in charge of implementing massive New Deal programs.”

Rosenberg’s biggest job in the early years of the New Deal was heading up New York’s regional office of the National Recovery Administration, or NRA. “The theory behind the NRA was that as businesses competed for customers, they cut prices and wages in an ever-descending struggle to get the cost of production to its lowest point so as to maximize profit,” Gorham explains. “The issuance and enforcement of hundreds and hundreds of legalistic fair-practice codes and a ban on unfair trade would, so went the theory, stimulate business recovery.” In practice, it was an impossible task that flew in the face of American capitalism. Rosenberg tried her best, but a Supreme Court decision in 1935 found the National Industrial Recovery Act, the enabling legislation of the NRA, unconstitutional, and her job ended.

Her next job was as regional director of the new Social Security Administration in 1936. With three telephones on her desk and an army of hundreds of employees in thirty-two field offices, Rosenberg still found time to hear about the problems of individuals. “Among the 1,050 walk-ins in one week in 1936 was an impoverished elderly couple, worried that they would have to split up after nearly fifty years of marriage,” Gorham writes. Insisting that they speak to “Miss Government Lady,” the couple was taken to Rosenberg, who comforted the sobbing woman. “A few phone calls later, Anna had arranged for enough public assistance to keep the couple in their apartment.”

When America entered World War II, Rosenberg helped devise the War Manpower Commission and served as its New York regional director. She dispatched the overabundant labor in New York to areas of the country with shortages, including Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where the atomic bomb was being built and tens of thousands of workers were needed. In fact, she was in on the Manhattan Project secret, something even FDR’s last vice president, Harry S. Truman, didn’t know about. She was involved in mediating labor strikes and threats affecting crucial war industries, urged FDR to end segregation in defense jobs, and advocated for high-paying defense jobs for women.

FDR also enjoyed her company. She was a pretty, vivacious woman famous for her stylish hats, with a wonderful sense of humor, and she joined the president at many of his daily cocktail parties. Working often from an office in the White House, she had ready access to the president (unlike some members of his own cabinet). The digital version of his calendar, FDR Day by Day, shows her meeting with him 127 times between 1936 and 1945. In comparison, Labor Secretary Frances Perkins, who held a dim view of Rosenberg and considered her a rival, met with the president 89 times in that same period.

Shortly after the D-Day invasion in June 1944, FDR dispatched Rosenberg as his personal emissary to Europe, introducing her in a letter to General Dwight Eisenhower as “my warm friend.” She toured military hospitals in England, embedded with General George S. Patton’s Third Army (she called him “Georgie”), slept on the ground and ate K-rations, and interviewed soldiers about their post-war aspirations. Returning, she argued successfully for money for college to be added to the G.I. Bill, which had positive repercussions for millions of returning soldiers. FDR asked her to tour Europe a second time as the war was winding down, and though he died before she was due to leave, President Truman sent her on. She dealt with refugee problems and saw the horrors of a concentration camp, which had a profound effect on her as a Jew who would surely have met a similar fate had her family stayed in Europe.

She went on to serve in the Truman administration as assistant secretary of defense, surviving a challenge from communist hunter Joseph McCarthy, and served as an unpaid advisor to Eisenhower and Lyndon Johnson on matters from labor to civil rights. Although she supported John F. Kennedy, he was notorious for the lack of women in his administration, depending on her instead as a master fundraiser. She organized the birthday gala for his forty-fifth birthday and was sitting beside him when Marilyn Monroe sashayed out in a skin-tight gown and sang a breathy “Happy Birthday, Mr. President.”

Gorham’s admiring, gracefully written, and well-documented biography resurrects the life and contributions of a worthy woman who deserves to be remembered.