The First Campgrounds Took the City to the Wilderness

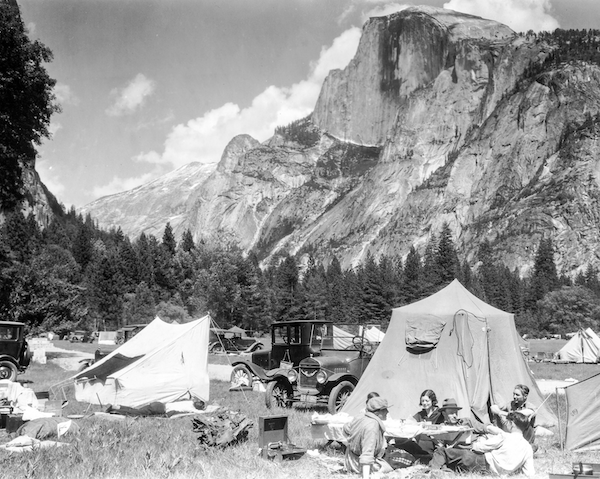

Overflow Crowd of Campers in Stoneman Meadow, Yosemite National Park, 1915. Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

A camping area is a form, however primitive, of a city.[1]

—Constant Nieuwenhuys

There is a deeply satisfying immediacy about the prospect of establishing and occupying an encampment for the night—clearing the site, erecting the tent, chopping wood, building a fire, and cooking over the live flame—that undoubtedly suggests a meaningful connection to landscape, place, and the rugged life of backwoods adventurers. As they reach their numbered campsites by foot, automobile, or RV, modern practitioners of the craft no doubt give little thought to the ways in which campgrounds have reshaped this powerful experience of nature in ways both subtle and fundamental.

Recreational camping emerged in the United States after the American Civil War as a form of escape from the hustle of city life. Spurred by the 1869 publication of Adventures in the Wilderness; or, Camp-Life in the Adirondacks by the Reverend William Henry Harrison, aka Adirondack Murray (1850–1941), visitors flocked to the region in search of spiritual and physical renewal, marking what the historical geographer Terence Young characterized as the birth of the practice as we know it today.

Before this important book appeared in print, recreational camping had remained the exclusive province of wealthy enthusiasts who could afford to hire expert guides to lead them, build their camps, fish, hunt and prepare their food. As they casually set about to explore their surroundings, these new leisure campers were likely unaware that they themselves would have little hope of surviving this unforgiving American wilderness on their own. As demand surged, these individual camps made way for large, organized tours such as those the Wylie Permanent Camp Company began operating in Yellowstone National Park during the mid 1880s. The 1910 edition of the company’s Yellowstone brochure promised an experience that sounds remarkably similar to modern-day glamping, in which visitors overnighted in well-appointed tents built on sturdy wooden platforms and furnished with comfortable beds.[2] As they set out in the morning, these campers were secure in the knowledge that the next stop on the itinerary would offer the very same conveniences.

Paradise Valley Campground, Mount Rainier National Park, 1915. Courtesy of the National Park Service.

During the early part of the 20th century, the influx of affordable automobiles like the Ford Model T made it possible for prospective sightseers to reject the artificial trappings of these organized tours. Instead, these newly-minted motor tourists set out to experience the world on their own terms: "Thoreau at 29 cents a gallon."[3] Unfortunately for these hordes of intoxicated travelers, wild nature was often met with enthusiasm, but not always with high regard. Careless campers used streams as latrines and left behind unextinguished campfires and heaps of trash. Even the most respectful were not immune, since they might inadvertently consume water polluted by towns, factories, or campsites upstream. In an ironic twist, the very places that early enthusiasts like Adirondack Murray had championed for their thrilling scenery and regenerative properties were slowly turning into breeding grounds for diseases like typhoid and cholera long eradicated from urban agglomerations nationwide.[4] The noted expert Frank E. Brimmer (1890-1977) remarked dryly of this period that “The vandals sacked Rome, but what 12,000,000 motor campers may do in this land of the free, unless good sportsmanship is the keynote of camping, will make the inroads of the Huns look like a fairy story for juvenile consumption by comparison.”[5]

As a new type of spatial landscape during the 1910s and ’20s, campgrounds helped mitigate some of these destructive impacts. They did not close the door on increasing masses of visitors, but instead concentrated campers and their motor vehicles in designated enclaves often demarcated by fences or moats, sparing more delicate and ecologically sensitive natural areas. It is interesting to think of the convergence of these two trends: the independence afforded by the automobile, and the slow, progressive removal of agency caused by the protective enclosure of the campground. In truth, campgrounds came into existence precisely because of motor vehicles. For Murray and his contemporaries, siting the rustic encampment in direct proximity of a lake, river, or stream, and within reach of an ample supply of firewood, represented a strategic decision of great consequence. With the emergence of these new massive public facilities, however, the location of the encampment was no longer open for discussion: park here also meant camp here. Campgrounds offered motor tourists the persuasive illusion of roughing it in nature, albeit within a structured spatial setting.

Art Holmes, Summit Lake Camp Boundary, Lassen Volcanic National Park in California, 1932.

Courtesy of National Park Service, NPGallery Digital Asset Management System.

Little more than open fields serviced by a few latrines, a well and a large evening bonfire, the first campgrounds were characterized by overcrowding and loosely arranged clusters of motor vehicles, tents, and trailers. The Yosemite historian Stanford Demars observed that “It was commonly joked—and not without some truth—that the first camper to drive his automobile out of the campground on a holiday morning was likely to dismantle half of the campground in the process due to the common practice of securing tent lines to the handiest object available—including automobile bumpers.”[6] Over the next two decades, scores of additional controls such as length of stays, one-way roads, dedicated numbered plots serviced by parking spurs, firepits and picnic tables, would progressively shape the campground from a free and relatively open territory into the facilities we know and enjoy today.

Every summer now, over forty million Americans take to the open road in search of this powerful experience of nature.[7] They travel to state parks, national parks, and other federally managed lands. They summer at commercial campgrounds, like KOAs (Kampgrounds of America), or at private, luxury glamping sites advertised on Airbnb and Tentrr. Less discriminating campers even overnight their RVs in Walmart parking lots. Despite the hundreds of campsites available at popular facilities, demand has become so great that reservations must be booked months in advance of arrival using online websites such as reserveamerica.com, recreation.gov or campgroundviews.com, an amenity that offers prospective campers a Google Street View-like experience of many facilities nationally. Serviced by extensive networks of infrastructure and populated with automobiles, trailers, $300,000 RVs, massive tents, thick mattresses, coolers, stoves and other forms of specialized gear, each of the country’s 900,000 "lone" campsites, spread over 20,000 campgrounds nationally, functions as a stage upon which cultural fantasies are performed, often in full view of a nearby audience of fellow enthusiasts interested in the very same "wilderness" experience. As Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) keenly observed in his poem The Adirondacs, “We flee from cities, but we bring the best of cities with us.”[8]

[1] Cited in Charlie Hailey, Campsite: Architectures of Duration and Place (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana University Press, 2008), 62.

[2] Idem.

[3] "Two Week's Vagabonds," The New York Times, July 20, 1922, sec VII, 7. Cited in Warren James Belasco, Americans on the Road: From Autocamp to Motel, 1910-1945 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997), 8.

[4] Cindy Aron, Working at Play: A History of Vacations in the United States (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 224.

[5] Frank Brimmer, Coleman Motor Campers Manual (Wichita, KS: The Coleman Lamp Co., 1926), 62.

[6] Stanford Demars, The Tourist in Yosemite (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1991), 139.

[7] Based on the 2017 Outdoor Foundation Camping Report. Downloaded at https://outdoorindustry.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/2017-Camping-Report__FINAL.pdf. [visited 08.16.19]

[8] Ralph Waldo Emerson, “The Adirondacs,” in May-Day and Other Pieces (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867), 60.