What in the World is Oliver Stone Talking About?

Last week the director Oliver Stone caused quite a stir when, in describing his new Showtime mini-series, "A Secret History of America," he declared that Adolf Hitler was an "easy scapegoat throughout history… [who]'s been used cheaply." "We can't judge people as only 'bad' or 'good,'" Stone continued. Even Hitler was "the product of a series of actions. It's cause and effect. People in America don't know the connection between WWI and WWII." “You cannot approach history,” Stone added in reference to Stalin and Hitler, “unless you have empathy for the person you may hate."

The furor, as one can imagine, was immediate; not only from historians and Jewish groups, but journalists and politicians as well. As Ron Radosh wrote in his own scathing HNN reply to Stone and the director’s main consultant, the historian Peter Kuznick, it's hardly novel for academics to argue that Nazism was a product of external and internal circumstances. Without the First World War, Versailles Treaty, or the Great Depression, the Nazi movement could never have achieved the success that it did. And without the repeated social and political crises that defined the latter years of the Weimar Republic, Hitler would not have been named German Chancellor in January 1933. We don’t need “empathy” for Hitler to understand the way that people, even Hitler and the Nazis, were shaped by circumstances. So what in the world is Stone talking about?

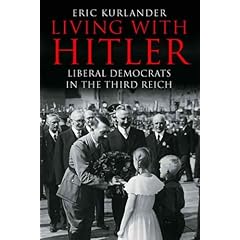

One can only speculate as to the director’s precise point of departure. But I’m going to presume that Stone, despite his penchant for sensationalism, is hardly going to make the case that Hitler was a decent human being. The question he probably intends to answer is the same one I address in my recent book, Living With Hitler (reviewed by Jeffrey Gaab in the September 2009 HNN newsletter): How could so many educated, liberal-minded Germans have actively supported, or at the very least passively accommodated, a fanatic like Hitler?

German liberals worked harder than most Germans to prevent the collapse of the Weimar Republic. But after fourteen years of turmoil and three years of rule by emergency decree, few were passionate enough about democracy to make it the chief platform for their opposition to Nazism. Many were cautiously optimistic that a majority coalition led by Hitler might restore a sense of order, authority, and national pride to the rudderless Weimar state.

After all, German liberals had already made uncomfortable concessions to nationalism, anti-Semitism, and authoritarianism in an unsuccessful attempt to stave off losses to their right-wing rivals. And the Nazi Party, unlike traditional conservatives, contained populist elements that appealed to many liberal voters. Like the liberals, the Nazis vilified Communism and the Versailles Treaty, advocated the right to national self-determination for all ethnic Germans, and promoted a Keynesian, deficit-financed fiscal policy that helped revive capitalism in the wake of the Great Depression. In their general ambivalence toward women’s rights, organized labor, and the welfare state, there were more than passing similarities between liberal and Nazi programs.

Moreover, there was ample space for liberal criticism and everyday opposition in the Third Reich, especially before the outbreak of the Second World War. When liberals failed to resist, at least intellectually, it had less to do with fear of arrest or persecution and more to do with a tacit desire to accommodate Hitler’s policies. Admittedly, liberals did encounter pressures to conform in terms of pursuing a career or maintaining a personal or professional relationship. Yet these kinds of pressures—including the necessity of joining Reich organizations, avoiding “minority” hires or toeing a politically palatable line—were not qualitatively different from those imposed, for example, by Wall Street law firms or across the American South in the 1930s.

Did German liberals feel “empathy” toward Hitler? Well, they certainly sympathized with many aspects of his domestic and foreign policy. Only when confronted by the abject criminality of the regime–– the escalating physical abuse of German-Jewish citizens; the Euthanasia program; reports of mass shooting of prisoners of war, Jews, and other minorities on the eastern front–– did many liberal democrats turn away from even a tentative endorsement of Nazism. By then, of course, it was too late.

How different was it in liberal democratic Britain, France, and the United States during the 1930s? All three countries embraced eugenics programs, racist immigration policies, and discriminatory legislation that differed from the Nazis’ more in degree than kind. Between the end of the First World War and the Kristallnacht pogrom of 1938, more African-Americans were lynched in the American South than Jews killed in Germany. In the American Midwest, Father Coughlin and Henry Ford held huge rallies and published popular tracts decrying the influence of Jews and immigrants. And after Hitler rose to power in 1933, all three countries appeased Nazi Germany because they perceived Communism to be a greater threat to their civilization, values, and economic system.

Certainly Nazi Germany was much less liberal and democratic than the United States, even before the barbarization of the Second World War. America’s largely idealist war against fascism forced many to revisit their own racist, chauvinist, and scientifically dubious assumptions. Nevertheless, had the United States experienced the extremity of the German experience in the First World War; territorial loss, occupation, and billions of dollars in reparations; and an even more devastating Great Depression, perhaps Americans might have evinced “empathy” for someone with views like Hitler’s.

It’s possible, as Ron Radosh suggests, that Stone’s secret history constitutes another iteration in the director’s conspiracy-laden oeuvre. But it’s also possible that, as a foray into popular history, it provides a useful antidote to the still widespread (if no longer academic) assumption that Hitler was some kind of “psychopathic God,” surrounded by criminals and supported by millions of illiberal, authoritarian-minded Germans. It might also cause us to think twice about whether we compare someone or something to Hitler. Hitler is no scapegoat. But too often over the past decades he has been taken out of historical context, by the left as well as right, and used as bludgeon to silence individuals on the opposite side of the aisle. Whether it’s comparing Saddam Hussein, George W. Bush, or Barack Obama to Hitler; or a public health care option and Roe vs. Wade to Nazi eugenics, many politicians and journalists have begun to distort the historical record beyond all recognition.

That is not to dismiss the utility of comparing Germany in the 1930s with the 21st century United States. In the face of a galvanizing terrorist attack, millions of Americans, Democrat and Republican alike, have supported two preemptive wars seeking the elimination of an amorphous international conspiracy spearheaded by a fanatical ethno-religious other. We have passed legislation restricting habeas corpus and countenancing torture. Facing a financial crisis, recession, and level of social inequality not seen since the 1920s, American taxpayers have allowed their government to invest a trillion dollars in the very corporations that created these problems, while accepting the proposition that extending health insurance to the poor, disabled, and disenfranchised is equivalent to Socialism.

Under these circumstances, Oliver Stone’s “secret history” might remind us of how susceptible all liberal democracies are, if not to Nazi-style fascism, then at the very least to nationalist demagogy, imperial(ist) overstretch, and the insatiable appetite of the military-industrial (financial) complex. Will it evince empathy for Hitler? I doubt it. Might it alert us to the circumstances that made Hitler’s peculiar cocktail of populist xenophobia, chauvinist militarism, and petty bourgeois resentment so attractive to millions of ordinary Germans? One can only hope.