Eleanor Roosevelt and Isabella Greenway: A Story of Two Political Women

On October 11, 2009, historians around the world took note of Eleanor Roosevelt’s 125th birthday with conferences and cake. The Arizona Historical Society marked the occasion by publishing a book containing more than two hundred letters between Eleanor and her long-time friend, Arizona congresswoman Isabella Greenway.

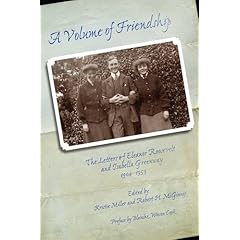

A Volume of Friendship: The Letters of Eleanor Roosevelt and Isabella Greenway illuminates the transformation of these two young society women into pragmatic political leaders.

Eleanor and Isabella met as debutantes in New York City, and quickly became friends. Isabella was a bridesmaid at Eleanor’s wedding to Franklin Roosevelt. Soon afterwards, Isabella married Robert H. M. Ferguson, one of Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders. The two couples honeymooned together in Europe. Three years later, Isabella’s husband was diagnosed with tuberculosis. The Fergusons and their children moved west, seeking health in the dry desert air. For the next twenty-five years, Eleanor and Isabella’s friendship was sustained through their letters. These letters reveal, almost step by step, how women entered politics a century ago.

At first, there was no hint of the politicians they would become. They were teenage girls from privileged families entering the social swirl of New York. Shy, bookish Eleanor was dismayed at the prospect, while beautiful Isabella became a popular belle. But both girls, influenced by prevailing progressive ideas, joined the newly formed Junior League to take part in social work.

Like most women of their generation who entered politics, Eleanor and Isabella had close ties to male politicians. In 1910, Eleanor’s husband, Franklin, was elected to the New York state legislature. Eleanor put aside her inhibitions to help him form alliances among the various interest groups.

Isabella’s husband, Bob, was a close friend and partner of Theodore Roosevelt. When TR ran for president in 1912, Isabella filled in for her sick husband by campaigning energetically on the candidate’s behalf. However, she felt she had to apologize for her unconventional behavior, writing to Eleanor, “Bob pushes me most shamelessly in.”

Both women clearly loved the political game. Eleanor wrote that, even though New York state senator Thomas Grady was “a reprehensible character,” he was still “a delightful speaker.” Isabella noted with amusement that, in the West, “no one is a proved politician till he’s been shot at a certain number of times in the Public Plaza!”

The two women also supplemented their observations by reading books about politics. Their letters refer to works such as Random Recollections of an Old Political Reporter, or The Citizen: A Study of the Individual and the Government.

America’s entry into World War I in 1917 provided more opportunities for further political education. Eleanor by then was living in Washington DC; as the wife of the assistant secretary of the Navy, she met a wide circle of influential people. Isabella was named to head up the New Mexico Women’s Land Army to help harvest crops while men were overseas. They each founded Red Cross chapters.

By the 1920s, Eleanor and Isabella had gained executive experience though their war work. They had been shaped by progressive ideals and exhilarated by political participation. They were newly endowed with the vote.

Furthermore, they had been strengthened by adversity. Eleanor had coped with Franklin’s infidelity with Lucy Mercer, then with his polio. Isabella’s husband had died of his tuberculosis. She married again, but her second husband, John Greenway, died just over two years later. The two women looked for meaning and purpose in their lives through political activity.

Both became members of the Democratic National Committee, Eleanor as the director of the Women’s Advisory Committee, and Isabella as Arizona’s national committeewoman. In 1928, they worked together on Al Smith’s presidential campaign. Four years later, they put their experience to use in Franklin Roosevelt’s presidential campaign. Isabella delivered the first seconding speech for FDR at the Democratic national convention, and worked behind the scenes to ensure his nomination. By 1933, Eleanor Roosevelt was in the White House, and Isabella Greenway was in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Eleanor and Isabella’s letters track their thirty-year metamorphosis into effective politicians. The letters also acquaint us with two of the most charismatic women of the twentieth century. We meet an Eleanor Roosevelt we have seldom seen, one who is preoccupied with her children, one who is wryly humorous (First Lady Ellen Wilson is “not overburdened with charm”). We also meet Isabella Greenway, a society belle who lived in tents in the desert, home-schooling her children, in order to prolong her husband’s life. The letters chronicle the widespread illness and premature death that haunted the lives of everyone, however privileged, in the first half of the twentieth century.

Today, friends keep up with each other through email, blogs, tweets, and Facebook. Few write long letters of the kind Isabella and Eleanor sent each other, sharing intimate details of their everyday lives. Such a volume of friendship will probably never be written in our own times or in the future.

We are fortunate to have, in this correspondence, a unique perspective of a transformative time in women’s history.