George Edwin Taylor, American Hero

Certainly the oldest and most inconvenient question asked of an historian—at whatever level—is either “Does History repeat itself?” or “Why should I have to read this?” Those are heady questions, and I do not suppose that I can answer either in 1000 words or less. I know for certain that I cannot answer them to your satisfaction. In a recent interview with Wisconsin Public Radio (WPR), I was asked both of those questions, and I nearly had cardiac arrest. I knew that both were coming sometime in the hour, but I was not in a mood to play that game. The answers are simple— “Of course history does not repeat itself” and “It is up to you whether you read it or not, you shouldn’t need a reason.” Of course, none of us give those answers—for we are talking “bread and butter” issues here.

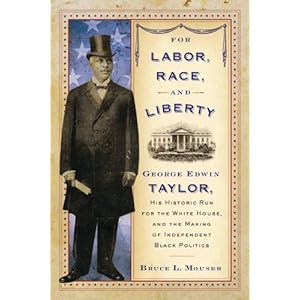

The occasion for the WPR interview was the publication of the biography of George Edwin Taylor, who was the first African American standard-bearer of a nation political party for the office of president of the United States. Somehow, Taylor’s story and his intriguing journey from urchin on the streets of Alton, IL and La Crosse, WI to his run for the presidency in 1904 had been lost in the dustbin of history, as were (and still are) those of many persons who might have served as heroes, had we only known of them.

On the surface, there was a bit of repeat in his story. He was born on August 4, he was 47 years old at the time of his run for the presidency, was raised by someone other than his biological parents, attended a private academy, was a gifted speaker, and rose from relative obscurity to national prominence within a decade. Taylor shared each of those attributes with Barack Obama.

But that was about as far as history repeated itself. Taylor’s run for the presidency was made within a racial party—the National Negro Liberty Party—which claimed to represent black interests but which lacked a single newspaper endorsement, despite the fact that there were more than fifty black newspapers in 1904. Taylor knew he could not win that election, but he was willing to fight for principles. He knew that the country that had given his race its freedom was then in the process of retreating from its promise of equality and was entering and accepting a phase of segregation and separation. His was a suicidal mission by whatever measure. And he experienced the political death that others had promised.

There was more to Taylor’s story, however, than merely his failed campaign for the presidency, but it was a truly dismal campaign. His party had initially endorsed Theodore Roosevelt as its candidate, only to reverse itself a day later and nominate a newspaper editor who—they then discovered—had failed to pay a fine in an earlier plea-bargain arrangement and who was rearrested on a warrant. The party then turned to Taylor, who at that moment was the president of the National Negro Democratic League, the Negro Bureau in the National Democratic Party. Taylor was stepping down from that post, and he was disillusioned and ready to try something different. The new party promised to put three hundred speakers on the stump on his behalf and to guarantee that his party and name would appear on the ballot of each state. None of that happened.

So the questions remain. Of course, history doesn’t repeat itself, but sometimes patterns form in the past that tell us about the fundamental character of a people or a nation. My wife—the sociologist—is interested in patterns, and she tells me that she is looking for trends and not rules. Maybe we historians are too focused on rules. I surely hope that I am not seeing a pattern.

Taylor lived through a remarkable period in black history. His was a time when African Americans were viewed as inferior, but it was nevertheless possible for him to achieve a level of accomplishment in Wisconsin that was unique. But he also was coming of age when Reconstruction was ending in the South, and the country was moving away from the promise of integration and equality. By the time of his run for the presidency, the country was in the midst of a full-scale retreat from civil rights. And the country—at least its white-dominated part—was studying the “Negro Problem” to discover the reasons for black inferiority and white supremacy. Blacks were about to enter a dark age in American history, and Taylor’s run for the presidency was the last gasp of that part of black America that dated from the Civil War. He shared the stage with Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington, but he was of a different class from W.E.B. Du Bois who was about to seize the reins of black America. He was a black populist while Du Bois was interested only in a talented vanguard that would dominate and lead a black renaissance.

So why study or read about Taylor? I am convinced that everyone needs heroes. At three score and thirteen, I still want them. Our heroes need not necessarily be successful. Jim Thorpe was one of my early heroes, but his victories were largely ignored. I would put Taylor in the same category. He achieved great things and ought to be recognized for his accomplishments, but he also let idealism and principles rule his action when there was no chance that either would obtain success. But I also cannot but repeat here the answer I gave to WPR when they asked that question. I answered, simply, that Taylor interested me and that I had followed the story until I got to the end of it. If others enjoy it and find meaning in it, I will be pleased. But I also am sure that someone—if they find my version fascinating enough—will find a reason to give more time to an aspect of Taylor’s life that I chose to minimize. That is what we do as historians. We investigate and chose and write. That is our job.