The Westboro Baptist Church vs. ... The Ku Klux Klan?

What does make the recent Arlington protest newsworthy is the presence of surprising counter protestors, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). While WBC protestors held up signs proclaiming “Thank God for Dead Soldiers,” “Mourn for Your Sins,” and identifying President Obama as the Beast of Revelation, the Knights of the Southern Cross (Virginia) passed out small American flags to mourners. The Knights, led by self-proclaimed Imperial Wizard Dennis LaBonte, protested the WBC’s anti-troop message. In a sense, some media outlets were stumped by the face-off of two derided, defamed, and unloved groups. While WBC traces the history of the independent Baptist church back to 1955, the presence of the Klan in the American historical landscape can be traced back much further. The KKK first appeared in the 1860s with the Reconstruction Klan and emerged time and again in twentieth (the 1910s-1920s, 1950s-1960s, and 1980s) and now the twenty-first century with the rising presence of white supremacists after the election of Barack Obama to the presidency (2008). Unlikeability is perhaps the kindest way to discuss the WBC and the KKK, but that term obscures the violence, physical and rhetorical, that both enact. Both are grouped under the label “hate movement,” which account for the surprise at the KKK’s stance against the WBC.

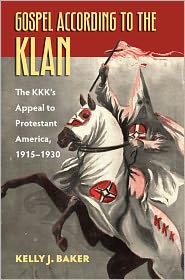

Yet, it is only on the surface that KKK and the WBC appear similar. While the WBC gleefully notes the anger/hatred of God for the American nation in relationship to sexuality, the Klan, in each of its incarnations, embraces and promotes a white Christian nationalism. The nation for the Klan is sacred, and it requires constant vigilance to guarantee America’s status as the nation among nations, divinely ordained and guided. The 1920s Klan, in particular, further believed that God played an active role in American history, siding with white Protestants as the “true” chosen American people. While WBC’s protests equate dead soldiers with divine punishment, my historical work on the 1920s Klan showcases the order’s long attachment to the nation as well as the fear, not glee, that Americans could face divine retribution for declining social values. Of course, the Klan’s vision of nation still remains strictly limited to citizens with white faces, “correct” religious faith, Protestant Christianity, and heterosexuality. Unlike the WBC, the order’s patriotism demonstrates its deep attachment to the nation and mythologized American freedoms and values. Soldiers emerge as dually important for the Klan because of their role in the protection of the U.S. and the ability to honor individual Klansmen’s military service.

CNN reports that the Southern Knights staged the counter-protest in support of freedoms, including free speech, which soldiers fought and died for. In the same article, Abigail Phelps, the daughter of the founder of WBC Fred Phelps, remarked, “They [the Klan] have no moral authority.” She furthers this claim by pointing out the Klan’s promotion of white supremacy as counter to so-called biblical positions on race. Who is the moral authority indeed?

What this protest and counter-protest make clear is the dissimilarity of movements placed under the moniker hate movement. While the Klan and the WBC are both despicable, their despicability is unique, contextual, and historical. They share surface similarities, but their opposition at Arlington shows that their differences are more telling. Passing out flags becomes just as symbolically important as inverting them. And it’s not every day that news stories pause to ponder who holds the moral high ground, the KKK or WBC? The better question might be: what’s at stake in acceding moral authority to either? The Klan’s stance against the WBC does not negate their prejudice, religious chauvinism, or racism. They do not become the “good” guys in this “us versus them” reporting. The issue, then, is why does this event need bifurcation? If our only choice is between the WBC or the KKK, do we really want to choose? Perhaps we should pay more attention to how the coverage flattens the significant historical divisions of those we call the hate movement as well as their competing moral visions.