How Does My Lai Compare to the Incident at Haditha?

There are many sides in the ongoing historical (and political) debate about America’s longest war, the war in Vietnam. There are those who are not sure, those who feel it was unnecessary, and those who believe that the war was a necessary one in the battle against communism during the Cold War. Recent press reports about the possible killings of Iraqi civilians at Haditha, which are still under investigation by the military, bring up an event from the war that ended over three decades ago: My Lai (also known as Son My), where hundreds of South Vietnamese civilians were slaughtered.

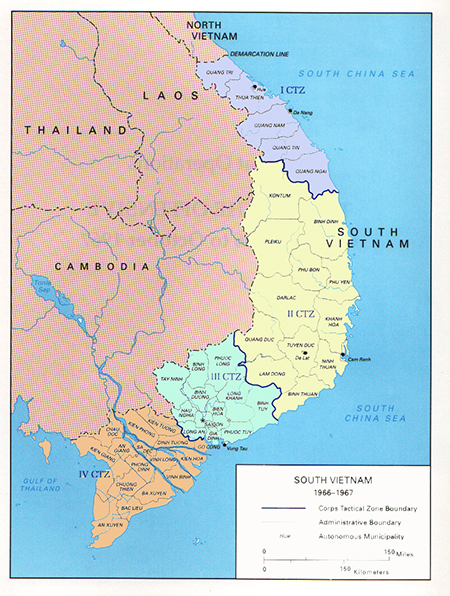

Where is My Lai? My Lai is a small hamlet within the Son My village in the Quang Ngai province of South Vietnam (now Vietnam). A map is shown below.

Credit: Wikimedia Commons/HNN staff.

When did the event occur? The incident at My Lai occurred on March 16, 1968. It was a part of an operation to clear the area of Viet Cong (VC) forces.

What led up to the event? Until 1954, Vietnam was part of French Indochina (during World War II it was controlled by the Japanese and liberated by the British who returned the area to French control). The French faced difficulties in maintaining control and soon were defeated in 1954 at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu by the Viet Minh, who were led by Ho Chi Minh, a popular leader who once had asked Harry Truman for help (Truman ignored him). After the defeat of the French, Vietnam was divided in to a communist North Vietnam led by Ho and backed by the Soviet Union, and a democratic South Vietnam backed by the United States.

According to the Geneva Accords, signed in 1954, an election was to be held to unite the country under a single goverment in two years. Ho was widely expected to win the election. The Eisenhower administration, worried about a communist victory, spurned elections and dispatched military advisors to South Vietnam to help the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). President Kennedy continued sending advisors; some 16,000 were in place at the time of his assassination. In 1965 his successor, Lyndon Johnson, began sending in combat troops. By the time of My Lai, America had an army of half a million in Vietnam.

Troops at My Lai were supposed to clear the area of Viet Cong. The high concentration of VC and communist sympathizers earned the area the nickname “Pinkville.” Prior to the incident, the soldiers involved were warned to expect engagement with Viet Cong forces. It was expected that the women of the village would be gone and the men would possibly engage the successful 48th VC Local Force Battalion. However, this would not be the case.

What transpired at My Lai? Company C of the 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry, which was part of the 11th Infantry Brigade, 23rd (Americal) Division was commanded by Captain Ernest Medina. His men, expecting to find the VC force, instead found women, children, and old men. Medina’s men, particularly those in 1st Platoon led by First Lieutenant William Calley, Jr., ran wild. They indiscriminately shot people and then rounded up survivors, led them to a ditch and shot them. More villagers were killed when their huts and bunkers were destroyed by fire and explosions. The killing only ceased when helicopter pilot Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson landed his chopper between the soldiers and the fleeing Vietnamese. According to a museum at My Lai 504 Vietnamese perished that day.

What occurred after My Lai? An attempt to cover up the incident lasted for a year. Then an Army investigatory board took charge. Out of the thirty persons aware of the event -- most of whom were officers (including the division commander) -- only 14 were charged with crimes. All except Calley had their charges dismissed or were acquitted. Calley, whose platoon was accused of killing 200 civilians at My Lai, was charged and found guilty of the murder of 22 civilians. He was sentenced to life at hard labor. This sentence was reduced to 20 years by the Court of Military Appeals, then ten years by the Secretary of the Army. Finally, having been deemed a “scapegoat” by the public, Calley was paroled by President Nixon in 1974. In 1998 Hugh Thompson and two other members of his chopper crew were awarded the Soldier’s Medal for gallantry, the seventh highest award a soldier can earn.

How did My Lai compare to what the enemy did? According to Lam Quang Thi, a former South Vietnamese general, the press coverage of the war by the U.S. was biased. In his book The Twenty-five Year Century, he noted that the media gave scant attention to Viet Cong atrocities such as the murder of 4,000 civilians in the city of Hue during the 1968 Tet Offensive.

How does My Lai compare to the incident at Haditha? News reports refer to a massacre at Haditha. But what makes a massacre a massacre? History notes an event known as the Boston Massacre, in which British soldiers killed five persons in March of 1770. When examined, Webster’s defines massacre as “the wanton killing of a large number of human beings.” While the killing of one person is a bad thing, the term massacre seems to have been the triumph of propaganda rather than reality. It does, however, properly describe My Lai in which hundreds were killed.

In Vietnam American and ARVN forces faced a regular North Vietnamese Army (NVA) as well as the Viet Cong, who primarily relied on guerrilla tactics. In Iraq, there is no standing regular enemy army facing our troops. Rather, U.S. troops face a terrorist force that uses tactics similar to the VC, which makes determining friend or foe difficult, as terrorists can easily blend into regular society.

Sources

Definition of massacre from Webster’s Dictionary.

Tucker, Spencer C., Ed. “My Lai Massacre”. The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War. Oxford University Press, 1998. 280-1.

Lam Quang Thi. The Twenty-five Year Century. University of North Texas Press, 2001. 192.

Correction: A previous version of this article displayed a map which incorrectly marked Quang Ngai Province as within the II Corps tactical zone. The province was in fact in the I Corps tactical zone. We regret the error.