It's Time Mississippi Established a Truth and Reconciliation Commission

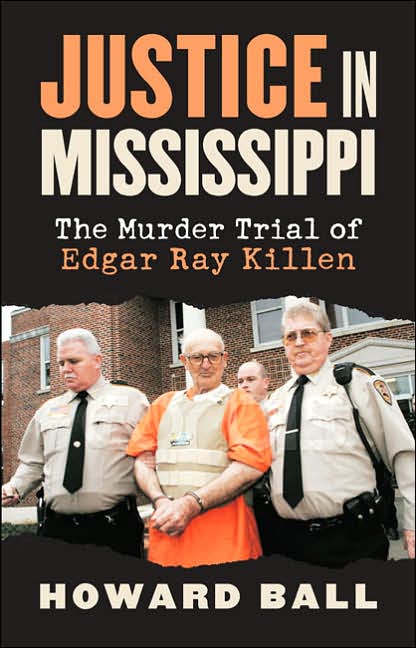

One of my tasks, in telling the story of the 2005 trial of Edgar Ray Killen for the murders of Schwerner, Goodman, and Chaney, is to examine the nature of the change by looking at the individuals involved in the 2005 criminal proceedings in the Neshoba County Circuit Court: Edgar Ray Killen, the defendant; the lawyers on both sides; the judge; the jurors; and, most important, the ordinary people who live and work in Philadelphia and in Neshoba County, Mississippi.

I believe it is an important story for it will try to uncover the true character and extent of change in a state and region that has, for centuries, been committed to a set of revered principles based on a fundamentally anti-democratic notion: Racial and ethnic superiority of and privileges for the white Anglo-Saxon community.

The trial itself laid out the facts—all of them—surrounding the murders of the three young men. Will this “outing” of the truth lead to reconciliation and the overcoming of Mississippi’s anti-democratic belief? After all, it is the one value that has been axiomatic in Mississippi for centuries. Over 140 years ago, America’s bloodiest, most costly war (in terms of human lives lost) took place between the North and the South. It occurred because of the South’s insistence on the inviolability of its sacred beliefs about slavery and racial superiority.

And, in the years following the end of the Civil War, this regional allegiance to racism continued, oftentimes accompanied by public, community-style lynching parties, economic intimidation, violence and murder in the night. At different times in the South’s post civil-war history, the Ku Klux Klan was born and resurrected to help ensure the maintenance of white racial superiority as well as white economic and social and political privilege.

The Killen trial’s story is a prism through which to gauge the nature of change in a city, a county, and a state that have resisted change using a wide variety of strategies—economic, political, violence, and murder—for hundreds of years.

Beyond the re-opening of cold murder case files and the conviction of old Klansmen for their actions almost a half century earlier, the Killen trial story is one that displays the regenerative energy of decent people who have come to recognize the value and the imperative of truth and reconciliation; of openness and freedom, in a democratic society.

Susan M. Glisson, the Executive Director of the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation, has been an invaluable asset to those in Mississippi who want the truth outed. Glisson’s recent observations underscore the growing impact of the concept of a TRC-style process in Mississippi.

We have come far in the South, but still there is pain associated with acknowledging those dark days. Partly that pain exists because many of these issues remain unresolved and operational in current policies and daily interactions. So we must frankly confront that past for those wounds to heal, so we can begin to understand the legacy of racism that continues to harm us today in education, health care, housing, and other indicators.

Observing the goings-on and the Statements of the Philadelphia Coalition and others, it is clear that the idea of a “Truth and Reconciliation Commission” (TRC) process, expressed so well by Glisson, has become an operative one for many Mississippians and others. As Susan told me, “the spirit of [Bishop Tutu’s] work animates what the Winter Institution does.”

Again and again, from Rita Bender Schwerner’s daily comments before, during, and after the Killen trial; from the Philadelphia Coalition’s Statements; and from journalists such as Donna Ladd, the Editor-in-Chief of the Jackson Free Press, the idea of a TRC-type process in Mississippi is seen as the way to reconciliation and greater equality. This process has also been adopted by the Philadelphia Coalition.

In a Statement issued immediately after the Killen guilty verdict was announced, the Philadelphia Coalition noted that the conviction of Killen was only the first step on the road to “seek the truth, to insure justice for all, and to nurture reconciliation” in Mississippi. “Seeking justice for the brutal murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner was long overdue. But we have only begun our work here.”

These three brave young men were not murdered by a lone individual. While a vigilante group may have fired the gun, the state of Mississippi loaded and aimed the weapon. The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission monitored and intimidated civil rights activists to prevent black voter representation. The White Citizens’ Councils enforced white supremacy through economic oppression. And decent people remained silent while evil was done in their name. These shameful acts have been little understood by Mississippi citizens.

For the Coalition members, much more had to be done to educate Mississippians about the systemic effects of past racial intolerance. “We must all understand how and why these murders and thousands of others occurred. We must understand the system that encouraged it to happen so that we can dismantle it. We must never allow it to happen again. We have the power now to fulfill the promise of democracy. Join us in that struggle,” was the Coalition’s call to its neighbors in Neshoba County and across Mississippi.

The TRC process underscores the importance of telling the unvarnished truth about past events in order to move forward toward reconciliation between former “warring” enemies. Donna Ladd’s comments totally parallel the TRC concept as it was understood in South Africa:

We believe it is time that Mississippi natives actively tell their own stories, no matter how difficult they are. A new generation of Mississippians are ready to step up and demand honesty and justice.

In a similar vein, Rita Schwerner Bender warned against putting to rest the “dead past” before the state of Mississippi and its residents are educated about the terrible crimes and the injustices committed in the “people’s” name.

In a letter written to Mississippi Governor Haley Barbour after Killen’s sentencing, made public by her on July 7, 2005, she said, in part:

I am writing this letter because of recent and past actions of yours which are impediments to racial justice in Mississippi and our nation. Recently, after the verdict and sentencing in the Edgar Ray Killen trial in Neshoba County, you indicated your belief that this closed the books on the crimes of the civil rights years, and that we all should now have" closure." . . . People in positions of public trust, such as you, must take the lead in opening the window upon the many years of criminal conduct in which the state, and its officials, engaged. Only with such acknowledgement will the present generation understand how these many terrible crimes occurred, and the responsibility which present officials, voters and, indeed, all citizens, have to each other to move forward. . . .

[After talking about the symbiotic relationship between the state legislature, the state executive, the WCC’s, the Ku Klux Klan, and the State Sovereignty Commission, the letter concludes with the following comments.]

Certainly, as the present governor, you must be aware of this history. This history must be known and understood by everyone. I spoke with many people in Neshoba County who are striving to understand the truth, and who are burdened by the responsibility they carry with them for the actions of their community and their state. But, there are still too many people who see only what they are comfortable recognizing. . . . Until individuals and their government understand why they do have responsibility, they cannot ensure racial justice and equality. So, please do not assume that the book is closed. There is yet much work to be done. As the governor of Mississippi, you have a unique opportunity to acknowledge the past and to participate in ensuring a meaningful future for your state. Please don't squander this moment by proclaiming that the past does not inform the present and the future.

Her concerns about the impact of the Killen decision and the consequences of a truth and reconciliation process are echoed by others in and out of Mississippi.

One example of public officials refusing to act on past inequities was the recent U.S. Senate resolution apologizing for past Senate inactions regarding anti-lynching legislation that passed in the U.S. House of Representatives.

In a recent nationally syndicated column, William Raspberry, who was born and raised in Mississippi, noted that Mississippi’s two Republican U.S. Senators, Thad Cochran and Trent Lott, did not sign a U.S. Senate Resolution of Apology for the body's failure to enact anti-lynching legislation. He wrote:

OK, maybe I wasn't too surprised by Lott's nonparticipation. After all, he is the guy who was stripped of his party leadership role three years ago for opining that America would have been better off if Strom Thurmond had won his overtly segregationist 1948 presidential campaign. But Cochran, though conservative, is thought to be less wildly right-wing than Lott — what you might call a Mississippi moderate. So why was his name absent from the list of sponsors?"I'm not in the business of apologizing for what someone else did or didn't do," he told me."I deplore and regret that lynching occurred and that those committing them weren't punished, but I'm not culpable." The trouble with Cochran's explanation is that he did in fact sign on as a co- sponsor of bills apologizing for the government's treatment of Native Americans and for the World War II internment of Japanese-Americans. Why did he find it so difficult to apologize for the Senate's failure to deal with House-passed anti-lynching legislation? More than 4,700 lynchings took place in the years between 1882 and 1968, according to Tuskeegee Institute, with Mississippi leading the pack with 581. The resolution was symbolic, of course. So, in many ways, is the action that brought Killen to trial 41 years after the fact. But it is a powerful symbol of a desire to atone not just for the crime of murder but for the prevailing attitude that, for many white Mississippians, made lynching acceptable.

These “Truth and Reconciliation” declarations by Neshoba County residents have already made an indelible impression on many residents of the State. The question still unanswered is whether the demands for truth and justice and reconciliation will have a significant impact on others in the state—especially on publicly elected officials such as Mississippi’s Republican Governor, Haley Barbour, and its two U.S. Senators, Republicans Thad Cochran, and Trent Lott.

If a majority of Mississippi’s citizens ignore the message contained in these truth telling events such as the Killen trial, then the politicians in Mississippi, like elected officials everywhere, will take their cues for future actions from these silences. And the remaining vestiges of centuries of racial discrimination, in housing, health, employment, and education, may remain largely unchanged.

If this is the consequence of truth and reconciliation process begun by the Philadelphia Coalition, then South African Bishop Desmond Tutu’s warning may become prophetic: “Unless the gap between the rich and the poor, which is very wide, is narrowed, then you could just as well kiss reconciliation goodbye.”