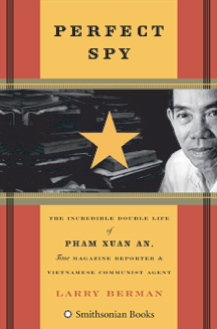

Perfect Spy: The Incredible Double Life of Pham Xuan

Why did one of the great spies of our century allow me to be his American biographer?

During the Vietnam War, Pham Xuan An was a highly respected Time Magazine reporter who turned out to be a spy for the North Vietnamese. He was a trusted source for the era’s best known reporters; his circle extended well beyond journalism to include the CIA’s Lou Conein, Edward Lansdale and William Colby. He was friends with the most notable South Vietnamese politicians and generals. Working for Time provided the perfect listening post and information access point for a spy.

The Communist Party recruited An as espionage agent X6, a lone cell member of the H63 intelligence network in Cu Chi. The Party chose a career in journalism as the best cover and developed a carefully scripted artificial life history, beginning with An’s trip to the United States in 1957 where he attended college as a journalism major. For the next twenty years An lived a lie and no one suspected because he was so good at his day job. An’s success later earned him promotion to Major General and Hero of the People’s Army-- one of only two intelligence officers during the war ever promoted to the rank of General and Hero.

The Communist Party recruited An as espionage agent X6, a lone cell member of the H63 intelligence network in Cu Chi. The Party chose a career in journalism as the best cover and developed a carefully scripted artificial life history, beginning with An’s trip to the United States in 1957 where he attended college as a journalism major. For the next twenty years An lived a lie and no one suspected because he was so good at his day job. An’s success later earned him promotion to Major General and Hero of the People’s Army-- one of only two intelligence officers during the war ever promoted to the rank of General and Hero.

When I first met An in July 2001, we spoke about a range of subjects, but never espionage. An was interested in my forthcoming book, No Peace No Honor: Nixon, Kissinger and Betrayal in Vietnam. He asked if we could meet the next day at the Givral coffee shop, located across the street from the Continental Hotel and within earshot of the National Assembly building. During the war Givral had been the gathering spot for journalists, correspondents, police and government officials—the place where rumors started, were tested for their staying power and where everyone hunted for the best story-line of the day. An held the title “General Givral” because it was here that he could be found dispensing tips that were so timely it was rumored he must be CIA.

In 2003 An became seriously ill with emphysema, spending five days on an artificial lung. His wife, consistent with Vietnamese tradition, placed many of his documents, notes, photos and other materials into a coffer so that An could be buried with his secrets. An did not die, returning home with just 35% lung capacity remaining. An oxygen tank was stationed nearby and about two hours into our conversation, An said he needed to lie down and take oxygen. He invited me to browse through his library. I began reading the personal inscriptions in An’s books. “To Pham Xuan An—My friend, who served the cause of journalism and the cause of his country with honor and distinction-fondest regards,” wrote Neil Sheehan. “For my dearly beloved An, who understands that governments come and go but friends remain forever. You have been a grand teacher, but a gigantic friend who will always be part of my heart. With love, and a joy in finding you after all these years,” wrote Laura Palmer. “For Pham Xuan An-A true friend through troubled times we shared in wartime. My very fond regards,” wrote Gerald Hickey. “To Pham Xuan An, a courageous patriot and a great friend and teacher, with gratitude” wrote Nayan Chanda. “To Pham Xuan An, the present finally catches up with the past! Memories to share and to cherish—but most of all a long friendship,” wrote Robert Shaplen.“For Pham Xuan An, my kid brother, who has helped me to understand Vietnam for so many years, with warm regards,” wrote Stanley Karnow. “For Pham Xuan An—who taught me about Vietnam and the true meaning of friendship. To you, the bravest man I have ever met, I owe a debt that can never be repaid. Hoa Binh,” wrote Robert Sam Anson.

I needed to write this story—about An’s life as an intelligence agent during the war, his career in journalism, his years in America, his friendships—the story of war, reconciliation and peace. I beseeched An to recognize that his biography should be written by a historian like myself and not just by journalists in Vietnam where the censorship boards he ridiculed still operated. An looked me straight in the eyes and said “OK,” telling me that he respected my previous books on Vietnam and he hoped young people in America could learn from his life about the war, patriotism and his admiration for the American people. He promised to cooperate with only one caveat, reserving the right to say “that is not for your book, because it may hurt that person’s children, but I tell it to you so you can see the rest of the picture, but please, never tell that story or give that name.” Through our last day together, An remained very concerned that something he might say would have adverse consequences not for him, but for others. In every instance I honored his request.

He also told me that he did not want to read the manuscript until published, citing a Vietnamese phrase “Van Minh, Vo Nguoi.” An was telling me that he could always find something in my writing that he did not like, but he would not sit in judgment of his biographer’s conclusions since he had chosen not to write his own story. That was our deal; in exchange, I had unparalleled access to a spy.

I was consumed with a sense of urgency. An was very weak and always spoke about death. “I have lived too long already,” was his mantra. Now that I had authorization, I decided to visit as often as possible, never knowing when he would be gone. It was because An knew his end was nearing that he opened up more and more, providing me with documents obtained during the war, dozens of personal photographs and correspondence, access to members of his network, friends in the United States and, most important, a visit to the back of his home filing cabinets—old and rusting metal chests in which dozens of mildewed documents are stored. I caught An at the same stage as Doris Kearns did with Lyndon Johnson, in the winter of life when a person accepts that their end is near.

Still, how could I be sure I was not just getting the final spin from the master spy with the perfect cover? Perhaps An would again demonstrate the same mental discipline and compartmentalization he used during the war, when none of his American or Vietnamese friends really knew him either. His name in Vietnamese translates as “hidden” or “secret.” An’s name was indeed his life.

I conducted research in archives throughout the United States, finding much material in the Papers of Robert Shaplen deposited with the Wisconsin Historical Society; in the Neil Sheehan papers at the Library of Congress; in the Frank McCulloch Papers at the University of Nevada; and in the Edward Lansdale Papers at the Hoover Institution Library. I also interviewed dozens of former colleagues and friends, including those who knew An from his time in at Orange Coast College. I would new primary source documents with me on each trip to Vietnam. An’s eyes lit up when he saw the tracks of his life and knew that I was formulating an independent interpretation well beyond what was permissible in his own country. That’s all he wanted at this final stage.

An also asked if he could use my mini-cassette recorder to tape farewell messages to some of his old friends in the United States. Too weak to write or type, An wanted to say thank you and goodbye, telling me that I could use whatever he said as background, unless he had already told it to me during one of our sessions, in which case it was for attribution. If the recipient gave permission, I could use it all for attribution. An also asked that I return personal letters sent to him by American friends.

Pham Xuan An died of emphysema on September 20, 2006, just eight days after his 79th birthday. His coffin lay in state for two days of public tribute before a funeral with full military honors. Yet, several wreaths at An’s funeral spoke volumes to the An who was not a spy and Hero: “To our beloved teacher Pham Xuan An, we will always cherish your wisdom and friendship,” from the Vietnam Project, Harvard University; “With out deepest gratitude for your counsel and encouragement,” from the Fulbright Economics Teaching Program; “In admiration and loving memory of Pham Xuan An,” from Neil, Susan, Catherine, and Maria Sheehan.