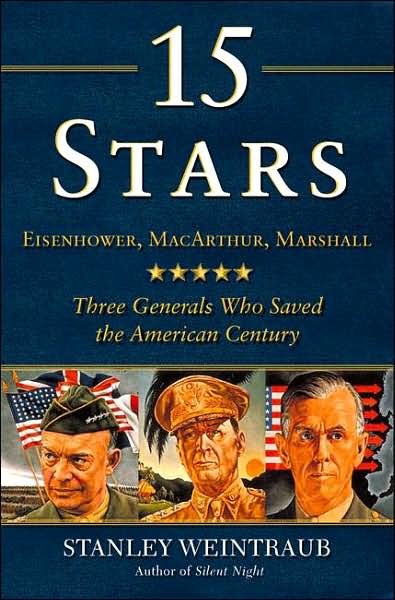

15 Stars: Three Generals Who Saved the American Century

They were each created five-star generals when that super-rank was authorized by Congress in December 1944. In the public mind they appeared, in turn, as glamor, integrity, and competence. Presidential talk long hovered about them. But for the twists of circumstance, all three -- rather than only one -- might have occupied the White House.

MacArthur, Marshall, and Eisenhower were each featured on the covers of Time, when that accolade, in a pre-television era, confirmed a sort of eminence.* All three would appear on postage stamps evoking their signature traits. Their immediately recognizable faces were remarkable indices of personality. MacArthur's hawklike granite gaze conveyed his headstrong, contrary tenacity. Marshall's seamed, inscrutable look suggested the austere middle America of portraits by Grant Wood. Eisenhower's ruddy, balding head and familiar grin brought to mind less the Kansas of his boyhood than the Everyman which admirers always saw in him.

Collectively they represented twentieth-century America at its crest. MacArthur was always City: Washington, Manila, Tokyo, and finally New York, where he retired to the thirty-seventh floor of the Waldorf Towers. Marshall was Suburbs, with a small-town upbringing in western Pennsylvania and an unpretentious home twenty miles from the capital in Leesburg, Virgina, where he was devoted to his vegetable garden. Eisenhower was Country, out of the rural Midwest, and ended his years on his manicured swath of model farm near Gettysburg.

Their trajectories, however upward, reflected their differences. Harry Truman's last secretary of state, Dean Acheson, once said of General Marshall,"The title fitted him as though he had been baptized with it." MacArthur, son of a general, was born and bred to be one. However ambitious, Eisenhower had his stars thrust upon him. Yet their military lives intersected for decades. MacArthur and Marshall were young officers in the newly captured Philippines, seized from declining Spain. Eisenhower emerged later, as a junior aide to MacArthur in Washington and again in Manila, until World War II erupted in Europe. The flamboyant MacArthur and the unpretentious Marshall were both colonels in France during World War I, the career of one taking flight there, to brigadier general and beyond, the career of the other plunging afterward to mere postwar captain, then agonizingly creeping back up, but seemingly never far enough. Despite MacArthur's four early stars -- at forty-nine -- when chief of staff, he would keep the future of his contemporary, who still had none in the early 1930s, in frustrating limbo.

Serving fourteen of his thirty-seven years in the army under both men, Eisenhower was an assistant to MacArthur -- invisible, and painfully aware of going nowhere -- and then deputy to Marshall, who rocketed him to responsibility and to prominence. In seven years with MacArthur, laboring in the arid peacetime vineyards, Eisenhower earned a promotion of one grade, from major to lieutenant colonel, changing the oak leaves on his collar from gold to silver. In seven months under Marshall -- under the vastly altered circumstances of global war -- he earned a constellation of stars and a major command.

Each of the three might have coordinated D-Day in Normandy, the most complex and consequential Western military operation in World War II. All three would be army chiefs of staff, Marshall and then Eisenhower becoming in turn the ostensible superior of their onetime boss, MacArthur, who brooked no bosses.

While MacArthur was sweepingly imperial in manner, the ideal viceroy for a postwar Japan where its humiliated emperor was reduced to a symbol, Eisenhower, genial and flexible, proved the exemplary commander of quarrelsome multinational forces. The self-effacing Marshall possessed such intense respect worldwide that when he entered Westminster Abbey, unannounced, to take his seat at the coronation of young Elizabeth II, the entire congregation arose.

*Marshall and Eisenhower would each be "Man of the Year" twice. MacArthur appeared on the cover of Time on December 29, 1941, in the week usually fixed for that accolade but it went the next week instead to President Roosevelt.

Excerpted from 15 Stars by Stanley Weintraub. Copyright © 2007 by Stanley Weintraub. Reprinted by permission from Free Press, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.