Was Dick Cheney's Self-Serving Claim to be Part of Congress Really Laughable?

The Vice Presidency was an afterthought at the Constitutional Convention. Late in those proceedings, the framers concocted the office as a means to deal with a perceived defect in the Electoral College. Without any conception of national political parties, the framers feared that narrow-minded presidential electors would simply vote for candidates from their own states, preventing the emergence of truly national candidates for president. Give each elector two equal votes, Pennsylvania delegate Gouverneur Morris suggested, and force them to cast one for someone from another state. National candidates could then emerge, if only from their second votes. To confer potential meaning on both votes, the runner-up would become Vice President.

The Vice Presidency was an afterthought at the Constitutional Convention. Late in those proceedings, the framers concocted the office as a means to deal with a perceived defect in the Electoral College. Without any conception of national political parties, the framers feared that narrow-minded presidential electors would simply vote for candidates from their own states, preventing the emergence of truly national candidates for president. Give each elector two equal votes, Pennsylvania delegate Gouverneur Morris suggested, and force them to cast one for someone from another state. National candidates could then emerge, if only from their second votes. To confer potential meaning on both votes, the runner-up would become Vice President.

Casting around for something for this Vice President to do, the Convention settled on having the person serve as presiding officer of the Senate, voting only in the case of a tie, in addition to standing next-in-line of succession to the Presidency. Without the Senate post, Connecticut delegate Roger Sherman worried, the Vice President “would be without employment” – which is clearly not a concern for Cheney. Having been elected as the second choice in a single contest for the Presidency, however, the Vice President would not have run with the President, and the two could easily be political rivals.

As the first Vice President, John Adams tried to make the most of the job but was thwarted at every turn. Despite Adams’s overtures, President George Washington never included the Vice President in his administration and viewed him as an officer of the Senate. Senators, however, quickly tired of hearing the Vice President speak on legislation that he could not vote on, and soon passed a rule prohibiting him from participating in floor debate. Venting his frustrations, the able and opinionated Adams denounced the Vice Presidency as “the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived” – but he stayed on for a second term in hopes of succeeding Washington.

By 1796, when Washington announced his decision to not seek a third term, two national partisan factions had formed in response to bitter divisions over domestic and foreign policy. Adams received the support of one; Thomas Jefferson of the other. When Adams narrowly won, he sought to bridge the growing partisan divide by offering Jefferson, as Vice President, a cabinet-level role in the new administration. Fearing his views could never prevail, Jefferson declined. Instead, he used his position as Vice President to lead the opposition. “The Constitution will know me only as a member of a legislative body,” Jefferson wrote to his closest partisan confidant, James Madison, shortly after the 1796 election. Up to this point, history supports Cheney’s claim that the Vice Presidency is a legislative post, albeit largely a make-work one, but stands against his claim of executive privilege.

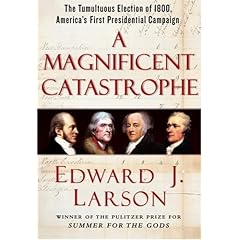

The election of 1800 changed everything. By this time, the two emerging ideological factions had hardened into distinct political parties. To prevent their opponents from gaining the Vice Presidency as a consolation prize, each party offered a ticket of two candidates and urged their electors to vote for both – equally. The result should have been foreseen. When Jefferson won, so did his running mate, Aaron Burr. They finished in a dead heat that, under the Constitution, would be decided by the House of Representatives, where neither party held a clear majority under the Constitution’s convoluted rules for resolving an Electoral College tie. A partisan free-for-all ensued that threatened the union.

After Jefferson finally prevailed and his party took firm control of Congress, the Constitution was amended to provide for the partisan election of President and Vice President by having electors cast one vote for each office rather than two equal votes. Thereafter, voters elected them as a team and increasingly they served as members of single administration.

Of course, Vice Presidents still held an independent Constitutional position and could assert their independence at their own peril. Vice President John Calhoun famously did so in 1832 over the issue of states nullifying national laws, and faced the wrath of President Andrew Jackson, who privately threatened to hang him for treason. Over a century later, Vice President John Nance Garner ran against his “boss,” President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, for their party’s 1940 presidential nomination. In acting as they did, clearly neither Calhoun nor Garner represented the administration. In contrast, other Vice Presidents have served as a part of the Executive Branch in virtually everything they did – think of Walter Mondale’s role in the Carter Administration, for example.

In short, the Vice Presidency is a curious post. History and the Constitution suggest that it is both a legislative office and, at least after the 12th Amendment, part of the executive branch. It all depends what the Vice President is doing. In his Constitutional role of presiding over the Senate – which today may involve little more than voting in the case of a tie and sitting beside the Speaker of the House during joint sessions of Congress – Cheney serves in the legislative branch. When functioning as a member of the cabinet and a presidential advisor, Cheney is not fulfilling any legislative duties envisioned under the Constitution. Executive privilege may apply, but with it should come the responsibilities of an executive branch official.