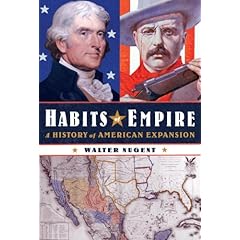

Habits of Empire: An Interview with Walter Nugent

Historian Walter Nugent is the author of the just published book: Habits of Empire: A History of American Expansion (Knopf, 2008). He is a member of HNN's advisory board. He was interviewed by email in June.

Q: America’s history is rife with institutions that were both lamentable and profitable. Did American empire-building take hold as an economic force, or do you argue that there were other equally important forces at work?

Q: America’s history is rife with institutions that were both lamentable and profitable. Did American empire-building take hold as an economic force, or do you argue that there were other equally important forces at work?

A: Economic interests certainly played a role. In what I call our first empire, the continental one by which we grew from thirteen Atlantic coast colonies all the way to the Pacific in less than seventy years, the settling of successive Wests meant economic opportunity for millions of homesteading families and others. It also involved grabbing land from Indians and others who were in the way of the settlement process. In our second, offshore empire across the Pacific and around the Caribbean, commerce was a major motive. William H. Seward, years before he bought Alaska, proclaimed that “the commerce of the world is the empire of the world.” Our third, post-1945 empire has involved globalization. But most of my book is on the first empire, where we learned the habit of empire-building. And that continental empire involved not only economic interests but ideology – Jefferson’s “empire for liberty,” the 1840’s “Manifest Destiny,” and other phrases – and certainly demography. The extraordinary fecundity of nineteenth-century frontierspeople allowed us to occupy and settle the land mass and solidify what was gained from diplomacy and conquest.

Q: In your mind, what was the most important moment in American history that cemented the notion of imperialism and empire-building in the political ethos and cultural conception of America?

A: I don’t see any one moment as decisive. The idea that we had a right, even a duty, to spread civilization and push back “savagery” is as old as the wars against the Powhatans and the Pequots. Beginning in 1782, when we acquired Transappalachia (without either conquering or, as yet, settling it), we reinforced the imperial habit with each successive acquisition. The majority of Americans, historically, have regarded that as natural and normal. Opponents there have been, to be sure, as in 1846, 1898-1900, 1968, and today, but they have seldom or only tardily prevailed.

Q: Thinking counterfactually, and given our knowledge of colonial American history, is there a viable alternative to the empire-building America that became?

A: Not likely, given attitudes toward Indians, Spaniards, Mexicans, and others along the way. The habit of empire seems to me too deeply ingrained, throughout our whole history, and too often reinforced, particularly by our relatively quick and easy capture of the continental land mass.

Q: When one thinks of empires and their sequel, great collapses, clashes of civilization or prudent contraction all come to mind as the “historical next step.” This is outside your role as a historian, but how much confidence do you have in America’s habits and what they might mean for us (as Americans) in the 21st century?

A: I suspect that the habit is still with us, and strongly. We have lived for over two centuries with the contradiction in Jefferson’s phrase, “empire for liberty.” We have had the forms and the rhetoric of a republic but have very often behaved imperially, i.e. imposing our view of things on others, benignly or forcefully, whether they wanted it or not. We’ve been warned about “imperial overreach” but done little to heed the warning. We don’t like to think of ourselves as an empire, because (as Gibbon taught us), empires decline and fall, and we don’t want to contemplate that. We prefer to think of ourselves as a people of frontiers – because frontiers can (in theory) go on indefinitely.

Q: What was your intention in writing the book?

A: At the outset I wanted to tie together the territorial acquisitions (traditionally the domain of diplomatic historians) with the settlement process (traditionally done by Western historians), which seem to me to be two sides of one historical coin. Further, I wanted to write a continuous narrative of all of the U.S. acquisitions, not just one or a few. And I wanted to do it with empathy for the positions of those who gave up the territory: the Indians, the Spanish, the Mexicans, especially, and after 1850, the Hawaiians, Samoans, Filipinos, and others. To get the “other sides,” I read Spanish, Mexican, and other documents and monographs. I had expected to stop with the conquest of the Southwest and the 1848 treaty with Mexico, but of course we kept on going, at first territorially, and later (and nowadays) through economic, political, and military power. Each acquisition, for me, became an episode in a continuous story, and together they comprise the historical foundation of where we now are.