Evangelicalism—the End of an Era?

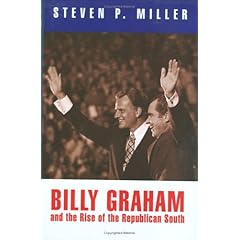

Historians love eras—if only because they offer an easy way to critique those other historians who dare think in terms of “the age of . . . . ” Recent developments might be giving historians of the increasingly prominent subject of American evangelicalism (specifically, political evangelicalism) reason to consider whether we have reached the end of an era. The age of public evangelicalism, should one desire to go down this interpretive path, began with the ascendance of Jimmy Carter, along with his subsequent nemesis, the Christian Right, and its roots lay in the work of Billy Graham and other prominent postwar evangelicals.

Historians love eras—if only because they offer an easy way to critique those other historians who dare think in terms of “the age of . . . . ” Recent developments might be giving historians of the increasingly prominent subject of American evangelicalism (specifically, political evangelicalism) reason to consider whether we have reached the end of an era. The age of public evangelicalism, should one desire to go down this interpretive path, began with the ascendance of Jimmy Carter, along with his subsequent nemesis, the Christian Right, and its roots lay in the work of Billy Graham and other prominent postwar evangelicals. I am not quite ready to declare myself on this matter yet (one does need to have future book projects, after all), but certainly the drivers of public narratives are veering in that direction. We have Newsweek editor Jon Meacham, a reasoned voice on such things, declaring the “end of Christian America,” a demographic shift that the George W. Bush years did much to conceal. Meanwhile, self-described “postevangelical” blogger Michael Spencer writes in the Christian Science Monitor of “a major collapse of evangelical Christianity” that will feature nothing less than “the arrival of an anti-Christian chapter of the post-Christian West.” Change has come, indeed.

On the other hand, back on January 20, Saddleback Church pastor Rick Warren dropped the “J” bomb at the Obama inauguration, violating the supposed tenet of American civil religion that God, not Jesus, is an appropriate higher power to invoke when praying for the nation. Actually, Franklin Graham, son of Billy, crossed this line back in 2001, as had others before him (including the elder Graham, who more tactfully invoked the “Son”). Both Warren and the younger Graham offer the best argument that something that can be called evangelicalism is still alive and, if not well, at least remains prominent in American public discourse. (Moreover, the numbers Meacham cites reveal that conservative Protestants have a growing stake in what is left of American Christendom.) Warren has earned the title the “next Billy Graham,” while Franklin can claim official status as heir. In their international ambitions, though, they also seem to be carrying forward the legacy of David Livingstone. How else to interpret Warren’s ambition to make Rwanda a kind of purpose driven country? Or Graham’s aerial relief efforts with Samaritan’s Purse?

So, talk of the end of an evangelical era might be a bit hasty. No doubt, it’s generally a good idea to avoid turning election results into zeitgeist moments. American evangelicals, after all, have proven themselves nothing if not entrepreneurial and ambitious. As sociologist D. Michael Lindsay demonstrated in his authoritative 2007 study, Faith in the Halls of Power, evangelicalism is more than a vibrant subculture; it has become a certifiable part of the American establishment. (Indeed, I would propose doing away with the subculture category altogether.)

But certainly some change is in the air. Rick Warren and, to a lesser extent, Franklin Graham provide evidence that the shifting political winds might lead conservative evangelicals to offer a more nuanced political perspective. Witness Warren trying to back away from his support for California’s Proposition 8. Franklin Graham, who did not inherit his father’s ability or desire to finesse the opposition, is at least striking a more conciliatory tone toward Obama. Both Warren and Franklin Graham are struggling to pull off what Billy Graham tried to do and eventually succeeded in doing—namely, transcending the labels that have defined post-Sixties America. On a fundamental issue separating modern conservatism from modern liberalism—the role of the state as an agent for the broader public good (as opposed to the state’s function in matters of national security or individual morality)—they are fundamentally on the conservative side. Even factoring in Bush fatigue, it is difficult to believe that Warren or his purportedly postpartisan peers really prefer to have a liberal Democrat in the White House. But Warren, at least, is ahead of the conservative curve in recognizing that ideology and partisanship are not the same things. That is because Warren has a third category to consider, theology. Not to mention a fourth, influence. He knows the political score.

Turning point or not, then, the age of the present seems an ideal time to begin the project of truly historicizing modern evangelicalism. Historians can take advantage of the perspective of three decades of very public evangelical influence. Fortunately, a new evangelical history is well under way, as recent or forthcoming books by Eileen Luhr, John Turner, Darren Dochuk, Dan Williams, Bethany Moreton, and others suggest. Precisely because the evangelical moment might be ending—or fundamentally transforming, or hiding under a bushel, or something else significant—such efforts may be timelier than ever.