Historic Change in Japan?

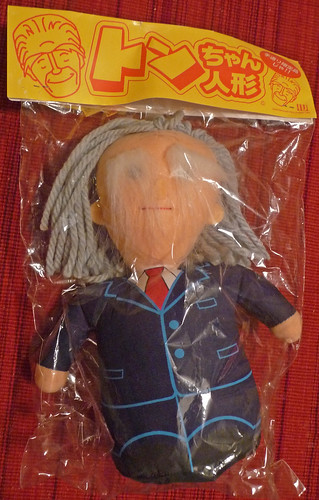

Last time I lived in Japan, in the mid '90s, the LDP lost control of the Diet, Japan's parliament, and for a year and a half there was a Socialist Prime Minister in charge of an implausible coalition between the Japanese Socialist Party (JSP) and the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). The JSP commemorated the event with"Ton-chan" dolls highlighting the bushy eyebrows and grandfatherly face of PM Tomiichi Murayama. (Japanese names are here rendered in the Western fashion: personal names followed by surnames.) It was, of course, noted at the time that it had been forty years since a non-LDP PM – and a Socialist, to boot -- had led Japan, though the presence of the LDP in the coalition meant that they weren't, technically, out of power.

Last time I lived in Japan, in the mid '90s, the LDP lost control of the Diet, Japan's parliament, and for a year and a half there was a Socialist Prime Minister in charge of an implausible coalition between the Japanese Socialist Party (JSP) and the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). The JSP commemorated the event with"Ton-chan" dolls highlighting the bushy eyebrows and grandfatherly face of PM Tomiichi Murayama. (Japanese names are here rendered in the Western fashion: personal names followed by surnames.) It was, of course, noted at the time that it had been forty years since a non-LDP PM – and a Socialist, to boot -- had led Japan, though the presence of the LDP in the coalition meant that they weren't, technically, out of power.

The Democratic Party of Japan, which just took control of the lower house of the Japanese Diet and is putting together a cabinet, was formed in the aftermath of that coalition: the more liberal elements of the LDP combined with the more moderate elements of the JSP. (See Curzon's translation of the useful chart from the Nihon Keizai Shinbun) Though the faction politics of the LDP did not divide neatly along ideological lines, some sense of policy alignment was starting to become clear within the party and its breakaway groups. This left a more conservative rump LDP and a more socialist rump SDP, and also, as a side effect, left the LDP again in charge of the government, in coalition with the Komeito and other conservative groups.

You could hardly tell from the news reports coming out of Japan at the moment. (Though bloggers like Adam Richards have been doing some excellent reportage.) I suppose that I'm not surprised by the lack of respect given to the mid-90s political turmoil: it was sloppy and inconclusive at the time, not the kind of clear-cut"historic" event that makes for banner headlines. But what came out of it was an LDP that was, honestly, destined to fail: instead of representing the middle two-thirds of the Japanese political spectrum, it represented a heavily right-oriented one-third, while the DPJ took a big chunk of what was left. Essentially, the LDP split, probably the natural end to a party that was a coalition to begin with, formed out of a Cold War fear that Japan's leftist parties might put aside their differences long enough to win control of the Diet. While it took a few elections, and another decade of disappointing economic stagnation, the left wing of the former LDP has overtaken the right wing of the former LDP, and a former member of the LDP is going to be Prime Minister. ( I don't think anyone's going to make plush toys out of Hatoyama Yukio, though he'd make a credible daruma.)

The survival of the LDP as the dominant party in Japan for so many post-war decades was a combination of historical luck, savvy leadership, and the cooptation of successful minor party issues. The collapse of the LDP was a combination of historical misfortune, a leadership vacuum, and the realignment of minor parties to create a viable alternative.

The creation of the LDP was a desperate maneuver: the two leading parties – the Liberal Party and the Democratic Party, direct descendants of the pre-WWII popular parties – joined forces to prevent the briefly-unified Socialist parties from gaining a plurality in the Diet. Under the leadership of PM Shigeru Yoshida, the LDP plotted a political course that became known as"the '55 System," which consisted of both political and policy elements. On the political side, the leaders of the Liberal and Democratic parties agreed to continue sharing power to stymie any leftist gains, rotating the Prime Ministership among the major factions and working out policy and organizational differences internally, the famous" consensus culture" of Japanese politics. For policy, the"Yoshida Doctrine" set three principles: reliance on the US for security and limited military expenditures; avoidance of international alliances and entanglements beyond the US; focus on domestic economic growth.

The success, and failure, of the LDP, could be summed up with the old truism about voters and their wallets: the LDP did very well during the era of high-speed growth (1955-1972), maintained its power during the era of slow growth (1973-1991), and lost control after failing to respond effectively to the era of zero growth (1992-present). In this sense, Yoshida simply had the good fortune to establish the '55 System at the exact moment when Japan's economy was starting too boom, and rode the wave as far as it would go. Yoshida's policy ideas were a powerful part of that wave, though, and part of what kept the LDP alive was the recognition by post-Yoshida leaders that elements of the original doctrine had outlived their usefulness.

In the late 1960s, PM Eisaku Sato reinforced part of Yoshida's doctrines by declaring his Three Non-Nuclear Principles – no production, possession or introduction of nuclear weapons into Japan, for which he won a Nobel Peace Prize – but he also weakened the government's focus on economic development. The LDP was losing ground to the leftist parties in the late '60s and early '70s on two issues: social welfare and the environment. Though Japan's economy was still booming, Socialist pressure for national health care and a social security system were gaining ground. And the environmental damage done by Japan's rapid re-industrialization was becoming increasingly obvious: in addition to egregious cases like Minamata mercury poisoning, the general level of air pollution in Japan's cities had reached epic proportions, requiring public monitors and strict work limits for outdoor labor like police work. So, Sato, and his successor PM Tanaka Kakuei, worked to steal those issues and implemented the Socialist plan under LDP auspices.

This did not mean that the LDP was shifting leftward by any stretch of the imagination: rather, the change was considered necessary to preserve the economic and physical health of the nation, and the LDP actually began to move farther to the right on other issues. During the 1970s, agitation by Japan's unrepentant monarchist nationalists began to gain traction and the LDP began discussing the possibility of"normalization," removing the anti-war Article IX from Japan's US-written post-war Constitution. That would, among other things, allow Japan to participate more actively in UN peacekeeping missions, and the LDP made a concerted push in the '80s to get Japan onto the UN Security Council.

Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone dominated the 1980s, and his emphasis on both educational and diplomatic"internationalization" marked a further shift away from Yoshida's doctrines. At this point, the LDP had become a more nationalistic party as well as a more international one, with a concerted effort to eliminate Article IX and renewed interest in honoring Japan's militaristic past by visiting the war memorial Yasukuni Shrine. At this point, the only ways in which the LDP still resembled the '55 system was that it was riddled with factions, each one with an independent fundraising arm and policy committees, and that it was heavily supported by Japan's rural districts. Needless to say, the independent factions have been a source of great instability in the 1990s, as the blocs shifted from party to party in search of electoral security, and the decline of the rural economy has shifted power to urban districts that tend to be less conservative.

After Nakasone's Prime Ministership, the late '80s and early '90s were a very bad time for the LDP. They had a series of scandals, punctuated by lackluster leadership which persisted through the collapse of Japan's stock and real estate"bubbles." The LDP lost control briefly, as I noted above, and shifted rightward, but the opposition parties were too fractured to gain ground in the short run. But as the post-bubble recession ground on into the"Lost Decade" and LDP stimulus packages and PM Junichiro Koizumi's liberalization reforms failed to energize the economy or the party, the Democratic Party of Japan, with its LDP veterans and Social Democratic base began to gain ground. His successors have been less impressive. Though the LDP put off elections as long as they could, the end result was the decisive DPJ victory.

The LDP started as a coalition and never really transcended its oligarchic beginnings. The Democratic Party of Japan is new, but it is a coalition of factions many of which trace back to the LDP itself. Is this"historic"? Well, it depends, of course. If the DPJ turns out to be more or less just like the LDP, then it's no more historic than Pepsi™ overtaking Coca-Cola™. If the DP turns out to be a genuinely center-left party which reduces international entanglements while successfully fostering economic development, it could portend a revival of the Yoshida Doctrine, though the '55 System seems to be well and truly finished.

(Note: a shorter version of this appeared at http://froginawell.net/japan)