India’s High-Stakes Foreign Policy

President Barack Obama’s forthcoming visit to India in November comes amid a noticeable increase in tensions in U.S.-Pakistan relations and a favorable climate for Washington’s ties with India. His visit to China almost exactly a year ago was a prickly reminder to Delhi of Beijing’s undeniable importance for Washington. However, Obama’s China experience ended with no significant breakthrough on relations with Iran or trade, heavily in favor of Beijing because of an artificially low exchange rate of the Chinese currency. The trade war has intensified in the past year, with Congress recently passing legislation that would punish China for undervaluing its currency.

On the other hand, the muted resentment felt in India’s official circles at Obama’s victory in the 2008 presidential election has evaporated to some extent. In a strange contrast to the negative sentiment about the Bush presidency in the United States and much of the world, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh of India even told the outgoing president at a White House news conference in September 2008, “The people of India deeply love you.” Such was the Indian prime minister’s gratitude to George W. Bush for delivering the civilian nuclear deal to India in the final months of his presidency.

Nearly two years on, when Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and India’s External Affairs Minister S. M. Krishna met in Washington in late September, they dubbed President Obama’s forthcoming India visit as a “defining moment.” The United States thanked India for its “commitment to Afghanistan.” Washington and New Delhi both have their own imperatives. Pakistan has not delivered the expected in the “war on terrorism,” but remains crucial for the U.S. administration. As Obama approaches his preferred deadline of July 2011 for starting a “drawdown” of troops from Afghanistan, India is emerging as a willing ally for America’s strategy in the region, and an enthusiastic agent to counter China, indisputably the superior military and economic power. As Obama ponders ways of reducing direct military involvement in Afghanistan after Iraq, the administration needs to contract out its role to proxies, with India the principal contender. The Obama administration and the Congress Party-led coalition government in India are playing for high stakes, but the stakes are higher for India in the long run.

At this point, I want to make some general observations that reflect the situation in South Asia, and how this situation has evolved. Foreign policy is to protect national security and prosperity. The goal is to develop relations as harmonious as possible, to avoid war which is destructive and bad for prosperity. Successful foreign policy depends on internal peace, because internal conflict almost always invites outside interest, if not intervention, and enflames unrest. India has a serious conflict in Kashmir and uprisings in other deprived parts of the country by tribal communities, inappropriately labeled as Maoists. India’s relations with neighbors are hostile, adversarial, and reflect distrust and suspicion. Yet the Indian elite’s consciousness is heavily occupied with achieving impressive statistics of growth—7, 8, maybe 10 percent. Questions such as: “How can we compete with, and beat, China and build military power.” India’s ambition is to become a superpower, and soon. All very impressive, but there is a cost—growing poverty, hunger, small farmers constantly squeezed, city slums and eviction of slum-dwellers. There are two very different narratives running side by side in rising India.

India’s foreign policy has become distinctly radicalized over the last sixty years. Its historical development is worth examining to understand the mindset and ambitions of India’s neoliberal elite today. I will look at certain noteworthy events that have played a determining part in this process in the decades gone by.

The 1950s were the most difficult period for India, an infant, fragile nation. Yet in a way, it was also the best period. India was known for its huge capacity to provide moral leadership in the growing community of emerging nations. It stood for values such as peaceful coexistence, non-alignment and the need for self-sufficiency to reinforce its independent status. It seemed willing to walk away from instant gains in the interest of these objects. Then two significant events happened in the 1960s: the defeat by China in October 1962, and two years later China becoming a nuclear state. Soon after came territorial gains for India in the 1965 war with Pakistan. Many Indians felt that their country had shaken off the 1962 defeat against China. But the Tashkent agreement reversed those gains under Soviet pressure, because the Indian army was required to withdraw from the territory it had seized from Pakistan.

Two further events happened in the 1970s. First, the 1971 India-Pakistan war resulted in the dismemberment of Pakistan and the emergence of Bangladesh in its eastern half. That was when India finally shook off the “China syndrome.” Second, in 1974 India carried out its first nuclear test, which triggered Pakistan’s nuclear program. With Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal a reality now, that advantage, at least with respect to Islamabad, has diminished. In 1975 the Bangladesh leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was assassinated in a military coup. India lost a close ally and much of the strategic gains made in the 1971 war. Looking back, the 1971 victory over Pakistan has been a mixed blessing. In the late 1980s Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi thought it was possible to impose peace in Sri Lanka’s ethnic conflict under the India-Sri Lanka Accord. He sent a large military force to the island state. It did not work out as had been intended. On the contrary, the feeling was reinforced among neighbors that India was behaving like the “big brother.”

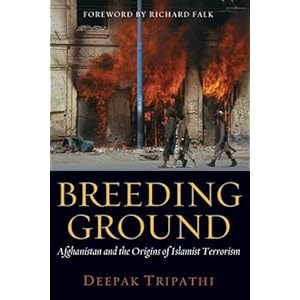

India went through a domestic trauma in 1992. Hindu fundamentalists demolished an ancient mosque in the northern town of Ayodhya, where they claimed Lord Ram was born. Communal riots followed in which thousands, mostly Muslims, perished. These events signified the rise of Hindu nationalism in India, a mirror image of the phenomenon of Muslim fundamentalism in Pakistan in the previous decade of Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. By helping Islamist groups in Pakistan and Afghanistan with weapons and money to fight the Soviet occupation forces, the United States had greatly contributed to the phenomenon of Islamic fundamentalism throughout the region. In the 1990s reverberations began to be felt across the border in the form of Hindu radicalization, with India witnessing the ascent of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party to power. Those events radicalized not only Indian society, but also the country’s foreign policy.

The irony was that India, with its illustrious past, reacted at best with muted criticism of the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s. And it came to support the U.S.-led invasion and occupation of Afghanistan in the first decade of the twenty-first century. Then, as now, the primary motive was to counter Pakistan and China. Today, the environment around India is unfriendly. So India has built a flyover—a super highway—to Israel, bypassing the Muslim and Arab world. That flyover goes from Tel Aviv straight to Washington. The space between India and Israel has been left to other players. As India and Pakistan remain locked in a decades-long cold war, each country maneuvers to have the United States punish the other. And each of the two rivals seeks to demonstrate that it, not the other, is the true ally of America in the war on terrorism. But as has been seen once again in recent years, abuse of military power against a nation’s own citizens, not to mention those of other countries, has a corrosive and destructive effect in the long run. India should consider whether its foreign policy would do better with a different balance of military and referent power.