Afghan Expert Thomas Barfield on Bin Laden's Death

Thomas Barfield is professor of anthropology at Boston University and the author of Afghanistan: A Cultural and Political History. I spoke to Professor Barfield by phone about the death of Osama bin Laden.

How will the death of Bin Laden affect the war in Afghanistan?

The death of bin Laden to some extent is symbolic of the war in Afghanistan. On the other hand, it sends a very powerful message to the Taliban—if America can get Osama bin Laden, America can get you. Taliban leaders have presumed themselves to be safe in Pakistan and they’re probably wondering if this is the beginning of an American endeavor to essentially deal with the problem in Pakistan.

Did it surprise you that bin Laden was found so deep inside Pakistan?

Yes, it did. It did surprise me—I presumed he was up on the frontier, but in another sense it didn’t surprise me in that how could he remain in Pakistan for ten years without some kind of acquiescence by at least some elements of the Pakistani government. In which case, why should he live in a cave?

So you believe that his presence was known by the Pakistani government?

It would be as if somebody were found on the outskirts of West Point in the United States. I find it very hard not to believe they knew. How many people knew or what level of acquiescence, that’s a bit difficult to determine, but if you were going to hide out in Pakistan, living in the largest mansion within less than a kilometer of Pakistan’s elite military academy—that’s hiding out in plain sight.

What does this mean for the relationship between the United States and Pakistan, since, as you say, it’s almost obvious—

But it’s been obvious that Pakistan has been playing both sides since 2001. The irony now is that Pakistan is saying, “well, you know, it’s a really good thing that bin Laden is dead now,” and with a straight face, if not taking credit for bin Laden’s death, at least pretend like they were informed of the decision to kill him.

I think it could work both ways, though. At one level, it’s very embarrassing to Pakistan because they’ve denied he was even in Pakistan. Having the United States find him in a suburb of your capital… It’s egg on their face. But, on the other hand, Pakistan has recently been getting rather aggressive in terms of telling the Americans “you shouldn’t do drone strikes,” talking about blockading supplies going into Afghanistan, etc. It makes me wonder if Pakistan may decide to back off a bit. There are limits to what you can get away with, and it wouldn’t surprise me if bin Laden’s death has the paradoxical effect of improving relations, at least temporarily, as a way for Pakistan to improve its bona fides once again. Periodically, Pakistan seems to cooperate when America gets too frustrated, as after all we fund the Pakistani army.

The New York Times reported that local residents in Abbottabad thought the compound was inhabited by a family from the frontier area, perhaps Peshawar. What is the relationship that the frontier has with Afghanistan and Pakistan? The borders were established by the British—

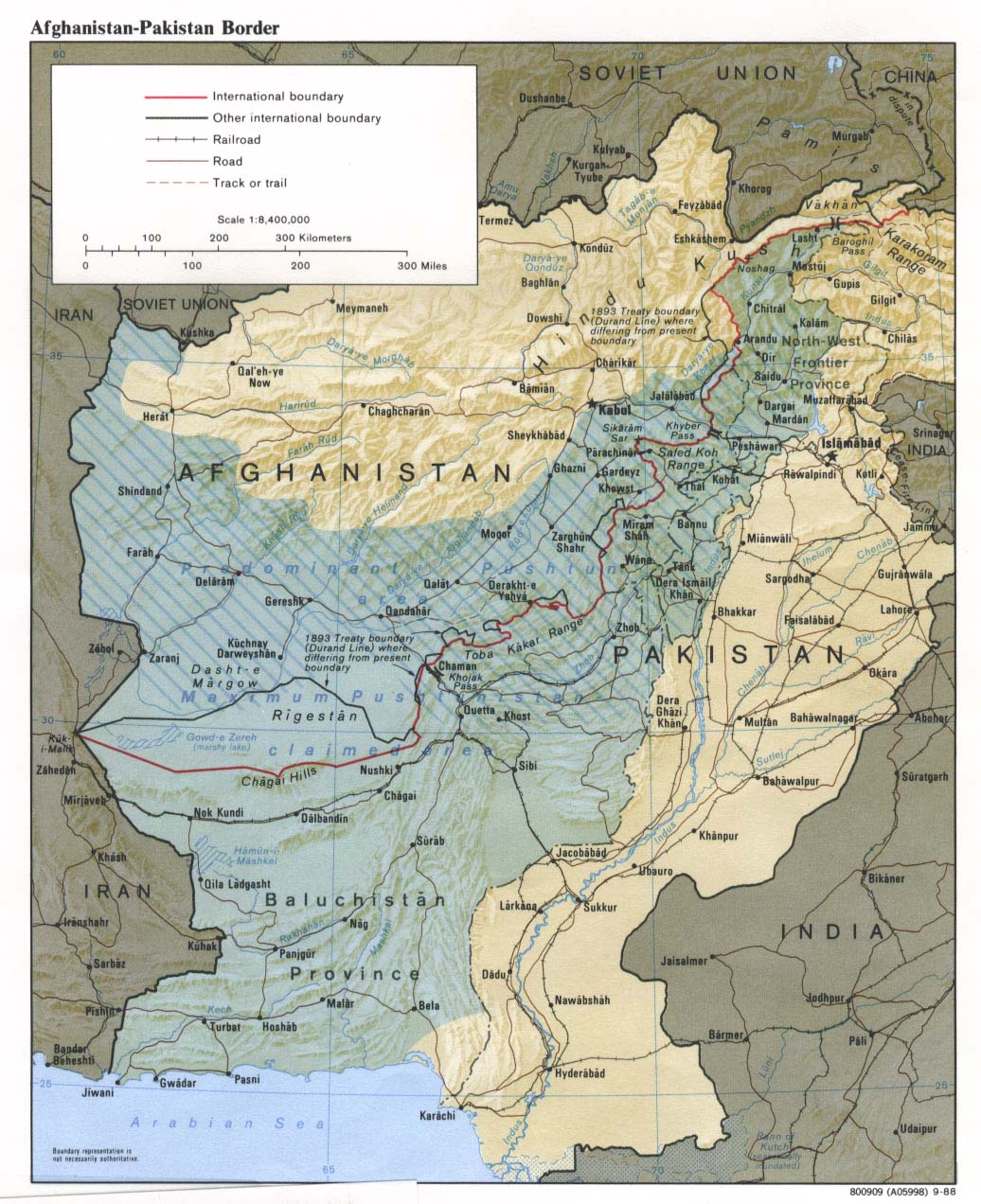

Actually, the border was established in 1893 by Henry Mortimer Durand, who surveyed the border and got the emir of Afghanistan to agree to it. The Afghans claim it was a line of demarcation and not an international boundary. The British were laying out zones of control, so what they called the “administered tribal regions” were areas that regular law applied to, including places like Peshawar and other areas that were dominated by Pashtun tribal peoples but were ruled by the central government.

Then there’s what’s called the FATA—Federally Administered Tribal Areas—which were effectively allowed to run their own affairs under the British. This was a case of direct control versus indirect control. When Pakistan took over from the British, it basically maintained this policy. Within the tribal district, the tribes largely have autonomy. The interesting thing is that these regions are still ruled by the Frontier Tribes Regulation Act of 1903, which is a colonial-era law that allows for various types of collective punishment, among other legal mechanisms. Many people in the region feel that they are almost a Pakistani colony—they do not have the right to vote in Pakistani elections and they do not have representation in Parliament. On the other hand, Pakistan has stayed out of their affairs.

Many people from these regions have left to go the Persian Gulf or Pakistani commercial centers like Karachi for work, and the leaders in the tribal areas are of course in charge of the cross-border trade with Afghanistan. Some of them have become quite wealthy, so it wouldn’t be a surprise that someone from this region would appear outside the capital and build a mansion. It’s not entirely unheard of. But on the other hand, someone from Waziristan would probably not be moving into that kind of neighborhood so close to a military academy.

How would you characterize the relationship between Pakistan and Afghanistan since 1947?

Afghanistan has always considered Pakistan to be an illegitimate state. It was the only country that voted against Pakistan’s admission to the United Nations, on the grounds that when the British left India the plebiscite that was held should’ve given the people a choice between independence or joining with Afghanistan. The Afghans, since the independence of Pakistan, have pushed what is known as the Pashtunistan issue, in that the Northwest Frontier province should become an independent Pashtun state. That’s created a tremendous amount of hostility between the two governments over the years. And the fact is that Pakistan has never gotten an Afghan government—include their clients, the Taliban—to recognize the Durand line as the legal boundary between the two states. As far as the Afghans are concerned, it’s an illegitimate boundary. If you look at Afghan maps of the region, they shade that whole area—from the Khyber Pass to the Indus River—as Pashtunistan. By the time you include Balochistan, it’s about half of Pakistan that the Afghans have refused to recognize.

Historically, therefore, governments in Kabul have often allied more with India than Pakistan. This surprises some observers, because after all Pakistanis and Afghans are fellow Muslims, but because of this longstanding animosity governments in Kabul have often established good relationships with Delhi as a counterweight to Pakistan.

And so the big concern in Islamabad is a strong Afghan government that is aligned with India, therefore surrounding Pakistan?

Pakistan has long been paranoid of being surrounded by India. The fact is that the Afghan state long precedes Pakistan. Their point of view is that they’ve been there since 1747, they’re the ones who have controlled this territory, but it is true that Pakistan has wanted to make any government in Kabul its client. The Pakistanis thought they succeeded when they supported the Taliban, and they greatly angered a lot of Afghans during the Taliban period by referring to Afghanistan as Pakistan’s fifth province. That’s one of the reasons why when the United States invaded the Taliban fell apart so quickly—there was a lot of animosity within Afghanistan about Pakistani influence, and this undercut the Taliban’s claim that they represented the Afghan nation.

What did the Pakistanis get out of supporting bin Laden and sheltering him from the Americans?

Some people have claimed that the Pakistanis were concerned that if we ever killed bin Laden we would declare the war over and stop giving them money. I don’t see it quite that way, but I do think the Pakistanis have a long tradition of “storing” people who might prove useful to them in the future. This might have fallen into that category. Also, after a certain point, how do you admit that you didn’t know he was there eight years ago? They found themselves stuck after all of their denials.

I think the bigger issue, though, goes back to the Soviet war when Pakistani political parties began to try to appeal to their Islamist right wing as a way to hold power. Pakistan was established as a refuge for Muslims in South Asia from Hindu domination. It was not established as an Islamic state, which is to say a state with religious foundations. However, once it was founded, then the Islamists said, “well if we’re a Muslim state, shouldn’t we prove it?” What’s happened in Pakistan is that over the years each government has tried to prove its bona fides by implementing Islamic law. Particularly during the anti-Soviet war, this became ingrained in Pakistani politics. What you have going on now is a great fear of offending the powerful Islamist right wing, even though a lot of the people who rule Pakistan even today are secular in nature.

How will this afect the American mission in Afghanistan? Will we see troop reductions? Will we withdraw?

It’s an important symbolic victory but Al Qaeda had already changed the way it was operating and our concern in Afghanistan is this: what happens to ungoverned territories when groups like Al Qaeda move in? That’s what happened before 9/11. The death of bin Laden doesn’t change the fear that, in its current situation, if Afghanistan is not stable it reverts back to the problems it had back in the 1990s and we get a recreation of the problem we had before. We realized after 9/11 that these ungoverned spaces represented a danger to other places. We discovered they were the perfect places for terrorist groups to work outside the state system. We see the same problem with Yemen, though strategically it hasn’t reached the point that Afghanistan did in the 1990s. Somalia is another problem like that. And so our concern is not can you get rid of a few leaders but can you leave a stable situation behind so that the problem you fought to get rid of does not reoccur.