The Forgotten History of Milwaukee's Civil Rights Struggle

The annual Organization of American Historians meeting has been taking place this weekend in Milwaukee, a city most often associated with beers and brats; Harleys and heavy industry; white ethnics, labor unions and “sewer socialists”; Lavern & Shirley. What is less well-known is the important place Milwaukee occupies in the history of the modern black freedom movement.

The annual Organization of American Historians meeting has been taking place this weekend in Milwaukee, a city most often associated with beers and brats; Harleys and heavy industry; white ethnics, labor unions and “sewer socialists”; Lavern & Shirley. What is less well-known is the important place Milwaukee occupies in the history of the modern black freedom movement.

Between 1958 and 1970, a distinctive movement for racial justice emerged from unique circumstances in Milwaukee. A series of local leaders inspired growing numbers of people to challenge employment and housing discrimination, segregated public schools, the membership of public officials in exclusionary organizations, welfare cuts, and police brutality.

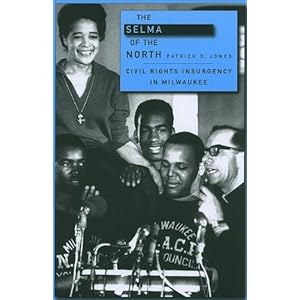

The climax of the movement era in Milwaukee came in 1967-68, when a white Catholic priest, Father James Groppi, and a group of young, inner-city black children and young adults led a dramatic open housing campaign for 200 consecutive nights, a campaign that provoked “massive resistance” from thousands of hostile whites, threw the city into tumult, drew the attention of the media, pundits, policy-makers, activists and onlookers across the country, and helped spur passage of the 1968 Civil Rights Act, better known as the Fair Housing Act. Shocking news stories and images of white counter-demonstrators attacking non-violent civil rights marchers on the city’s white, ethnic, working-class South Side, near the foot of the 16th Street Viaduct, prompted some to dub Milwaukee “the Selma of the North.”

Taking place during a transitional time of the civil rights era, many saw the open housing campaign in Milwaukee as “the last stand for an inter-racial, non-violent, church-based movement.” Catholics and Black Power advocates alike hotly debated the unique role of Father Groppi as the primary public face of what was, essentially, a militant Black Power movement. Comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory, who participated in the open housing campaign, claimed that Black Power adherents nationwide were becoming less anti-white because of the Milwaukee demonstrations, explaining, “What we are doing in Milwaukee is convincing a lot of cats that black nationalism is not a color, it’s an attitude.” In February of 1968, as liberal Democratic Senators Walter Mondale and Edward Brooke implored their colleagues to pass federal open housing legislation, Mondale raised up the struggle in Milwaukee from the floor of the Senate as a key example of the dire need for change. Even Martin Luther King, Jr., who had seen his northern experiment with non-violent direct action in Chicago the year before wreck on the rocky shores of similar white “massive resistance,” fraying relations with other local movement leaders and facing strong opposition from the Daley machine, noted the significance of the Milwaukee campaign. In a telegram to Father Groppi and other movement activists, King wrote that they had found the “middle ground between riots and sentimental and timid supplications for justice” that he had been searching for, providing a living example that militant non-violent direct action could be an effective tactic in the urban North.

Yet, despite the national attention the Milwaukee open housing campaign received at the time and the critical role it played in helping gain passage of historic federal legislation, the city and its struggle for racial justice has not taken its place alongside Birmingham and Selma in the mainstream telling of the civil rights era. In part, this is because the mythic popular narrative of the civil rights era privileges the Southern movement over the Northern black freedom movement, positioning it as a tidy redemptive story of American democracy, of American institutions overcoming obvious injustice, rather than the much more murky and complex history of achievement and failure movement scholars know it to be. This mythic narrative is more palatable to a majority of whites desperate for stories that go down easy and do not issue much of a contemporary challenge to persistent racial inequalities and the work yet to be done.

Northern movement stories like the one in Milwaukee, by contrast, are more difficult to clean up in this way because, as most people know, the urban crisis continues to rage in almost every mid-sized and large American city today. Despite the immediate achievement of the open housing campaign, Milwaukee continues to be one of the most segregated cities in the nation, ranking at or near the bottom of a host of indicators of racial inequality. In fact, when you look at those lists, it is Northern, not Southern, cities that dominate. As a result, to preserve and share the Northern movement history requires a reckoning not only with a forgotten past, but also with unresolved contemporary racial issues that most white Americans are reluctant to entertain, and which the mythic Southern narrative conveniently side-steps. But this is precisely why it is imperative that we begin to recover, teach and discuss these forgotten stories of Northern racial struggle. They help us better understand the roots of our on-going urban crisis and think in deeper ways about what meaningful and effective solutions to these problems might look like. So, as American historians gather up their briefcases and head back home after another successful annual conference in Milwaukee, it is my hope that they might take up this challenge and get to work excavating Northern movement stories. This is not merely an academic issue.