Death in the End Zone: NFL Concussion Crisis Play Packs Wallop

Headstrong

Ensemble Studio Theater

549 W. 52nd Street

New York, NY

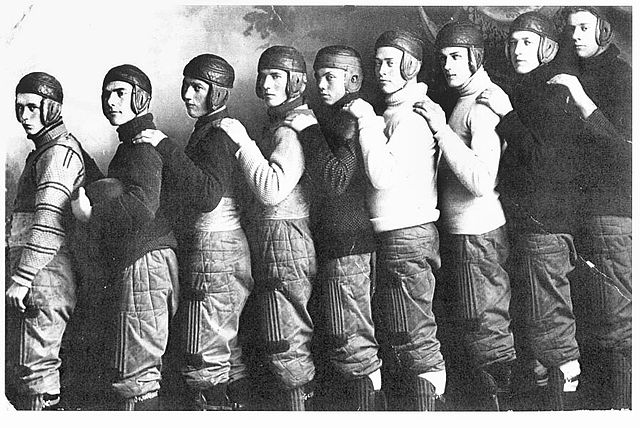

A typical football team, circa 1910

What happens to the brains of those huge National Football League players when the cheering stops? What happened to them back in the 1940s and 1950s, when they pulled off their much thinner leather helmets? Is it all endless glory, autographs, and pictures with fans, or do all of those thousands of hits to the head bring on concussion lifelong injuries?

Newspapers today are full of stories about the concussions that have brought about countless tragedies for NFL players. The Pittsburgh Steelers' Mike Webster suffered from amnesia, dementia, and depression before he died at 50, a death that his family said was brought on by concussions. Philadelphia Eagles defensive back Andre Waters sustained numerous concussions as a player before committing suicide at age 44, due to depression his family said was caused by the head injuries. Former San Francisco 49ers defensive tackle George Visger claims that he has lost most of his memory from concussions he suffered twenty years ago.

Now, dozens of former players are filing law suits against their teams and the NFL, charging that the mammoth professional football league did little to ensure their safety while making billions of dollars.

This fascinating story is explored in Patrick Link’s moving new drama, Headstrong, which opened last night at the Ensemble Studio Theater in New York. The slow-burning play, which has several explosions along the way, traces the efforts of a man from a sports foundation that studies concussion, Nick Merrill, to gain approval from the widow of an NFL star who killed himself to let the foundation’s doctors study his brain. Before he meets her, though, he has to lock horns with her dad, Duncan Troy, a former NFL star himself.

Troy frames the argument in the play. If the NFL goes overboard with protective equipment to ensure the safety of its players, what kind of a game will football become? Aren’t the hitting and the sacks a dramatic part of the game? Don’t people like football because it's so violent? A secondary argument is that as people age they have a host of mental health problems that aren't necessarily related to concussions.

An angry Nick tells Duncan and Sylvia that it isn’t just concussions that threaten football, but the hard hits in general. What ordinary person takes thousands of hits to the head from 300-pound linemen? Doesn’t all that head bashing wreck the brain?

In the end, it is Sylvia, bringing up a young child, who has to decide what to do. Does she really want to find out what killed her husband? Does the world?

The play runs along at a slow pace, but it picks up speed as time goes on and secrets about the characters are revealed. It's ultimately an indictment of the NFL, a wealthy sports organization that, it is charged, has done little to protect its players. Oh, to be sure, it is now, now that the spotlight's upon it. The coach of the New Orleans Saints was booted out of the game for a year for authorizing a ‘hit squad’ and posting bounties for hurting opposing players. The league is now doing studies on concussions and brain injuries. Playwright Link argues, though, that ever since the 1960s concussion have been a huge problem and they were overlooked.

"Well," defenders argue, "football is a violent game." The most famous phrase, used for decades, was, "play hurt."

The play opens dramatically with a dark set lit by stadium lights and the distant sound of a crowd at a football game. When the lights come on, the stage changes into Duncan Troy’s living room. It is turned into the foundations office later. One wall is filled with photos of NFL players and two television monitors broadcast NFL game films. Duncan Troy, who has dark secret himself, struts around in his Eagles shirt.

The director, William Carden, has done a fine job of letting the characters build the story slowly. Without his veteran skills, and the polish of Link’s script, this could have been one long, boring sermon on concussions. It is not. It is a tantalizing play that, in the end, asks questions we can’t answer: what damage does a concussion cause? What damage do all those hits to the head and body cause? Does that damage bring on other woes beyond the concussion, like depression and dementia? Is it worth it for $5 million a year?

Carden gets excellent performances from Ron Canada as Troy, Tim Cain as Dr. Moses Odame, head of the foundation, Alexander Gemignani as Nick, and Nedra McClyde as Sylvia. All of them play their roles quietly at certain times and loudly at others, building up and slowing down the rhythm of the play.

My only complaint is that Link doesn't go back earlier than the '60s. What about all those guys in the 1940s and 1950s who played with thin leather helmets and without the protective bar in front of their faces? What about all the guys who played in the years when spearing a player was all right and piling on considered a sacred part of play? And what about all those guys out of football’s history who were paid badly and could not afford medical care they probably needed?

The play is not particularly fair to the NFL either. The work that the league does to help those who are injured is ignored. The NFL created a committee, the Head, Neck and Spine Medical Committee, with a team of doctors to handle concussions studies. The NFL Players’ Union has its own, the Traumatic Brain Injury Committee. The NFL has also instituted new rules on head injuries, including sideline head exams after an injury on the field. Team doctors are beginning to pay more attention to concussions, too.

The gripping play by Link is another trumpet blast, and there are plenty of them these days, to get the NFL to do something about concussions and do a better job to protect its players. Their $20 million contracts aren’t going to help them in the cemetery.

PRODUCTION: Produced by Ensemble Studio Theater and the Alfred Sloan Foundation. Sets: Jason Simms; Video Design: David Tennent; Sound: Janie Bullard; Lighting: Chris Dallos.