Why Historians Should Be Vampire Hunters

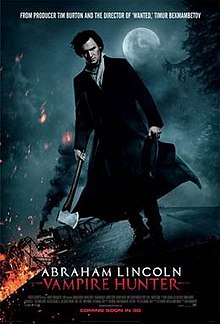

Theatrical poster for Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter

Historians seem more than a little befuddled by the film Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter. A recent piece in the New York Times by Harvard historian Jill Lepore mused about why "the literary bloodbath" of vampire tales has continued for decades. In the same piece, historian David W. Blight wonders if vampire stories are getting stale and if the Great Emancipator might have been a way to leaven the undead lump.

Reading this piece gave me the distinct impression that none of these historians have spent much time with vampire fiction, which is, of course, more than ok. Both are important scholars in the profession and have award-winning books to write that may keep them from watching much True Blood. Still, what Seth Grahame-Smith pulled off in the novel deserves a bit more from historians than a sort of "wow, vampires are kind of a thing right now" response.

I'm writing this not only as a historian of America's narratives of horror but as a college classroom teacher who has used the novel as a text with history majors. Indeed, we read it together in a class with the narcolepsy-inducing title of "The Historian's Craft." This is the class that all history majors, on pain of not graduating, have to take to learn methodology and other supremely boring things.

Why assign it in a class that is supposed to be a gateway drug for history majors? At least some of my colleagues probably think I'm trying to be trendy. Unfortunately your average college sophomore has nothing but undisguised contempt for anyone who tries to play the cool teacher (indeed, my demeanor screams "still plays D&D in his mom's basement" rather than trendy).

No, I wanted my students to think about how primary historical sources, the raw material of history, can be repurposed in surprising ways. If you've read the novel, you know that Grahame-Smith uses materials from Lincoln's speeches and 19th century newspapers to recreate the 19th century, indeed to give it a lived-in sort of feeling. Many of my students came away from the book wanting to read some good Lincoln biographies and histories of the era. I pointed them to David Blight, among others.

But we talked about another aspect of the book that I'm hoping serves as a major theme in the film. If you've read the novel, you know it's a dark rendering of America's secret history, the idea that dark powers have moved through the structures of American culture since the beginning. These evil powers, which in 1860 wanted a nation of their own, see human enslavement as a way to feed their appetites.

In my early discussions with my students, this was actually one aspect of the book that troubled me a bit. Didn't this equation of vampire conspiracies and slavery serve to undermine the struggle to move slavery to the center of the American narrative, especially in discussions about the meaning of the civil war? Fictionalizing it seemed to deal with a serious subject in a silly way.

My students helped me to see it a little differently. On some level, the elements of the fantastic in the novel point to deep, if hard to bear, truths about America. Grahame-Smith actually ties the great vampire plot to notions of "the Slave Power" in American life, an image employed by the abolitionist movement to describe how southern political influence, even over the Founding Documents, had left the republic twisted by inhuman bondage.

Moreover, its not that horror narratives of various kinds haven't always been a part of the story of slavery. Slaves in the colonial era created a complex folklore about the southern master class, worrying that slave traders were cannibals. My research uncovered at least one case in Louisiana which newly imported slaves became convinced that the masters were witches and vampires (after watching them drink red wine).

These tales of terror illuminate rather than obscure important truths. Slavery did represent a kind of dark magic in which legal fictions transmogrified the bodies of human beings into property. The institution of slavery did become a kind of cannibalism, swallowing millions from the African continent, digesting them in the rice and cotton fields in the relentless pursuit of wealth that characterized the alleged southern "aristocrats."

America needed a vampire hunter in 1860.

A few historians might worry about how the film might lose the novel's historical flavor in an effort to shape an action flick that, all signs indicate, will spurt enough gore to please the most jaded horror aficionado. I think the historical profession's angst should be focused elsewhere. Our students, and the general public, are unlikely to come away from the film convinced of its historical accuracy. But they do encounter poisonous fictions all around them that more insidiously mangle the past.

I recently found myself at the Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond, Va. Here amidst the rather sparse collections of buttons, uniforms, muskets and other military fetishes, we received an utterly worthless tour of "The White House of the Confederacy," Jefferson Davis' home during the war. Our guide (who insisted on being called Sgt. Major) gave us a series of ideological tirades about the "true" story of the southern cause. He managed to gloss over slaveholding and portray Davis, his cabinet and his warlords as fine examples of American patriotism. Unbelievably, he would not invoke the name of Abraham Lincoln, apparently in fear of raising his angry shade on him in the sacred precincts of the Confederate seat of power. The man who kept the US from becoming a balkanized patchwork that included a slaveholding imperium was simply referred to as "the Gentleman from Illinois."

Historians shouldn't worry that the general public might decide that Abraham Lincoln spent his free time staking and decapitating vampires. We have bigger worries given the amount of historical undergrowth that twines itself around so many of our sites of public history. There are, in reality, some very dark forces that need slaying in American memory and historians need to pick up the hatchet and start swinging.