Happy Birthday, Woody!

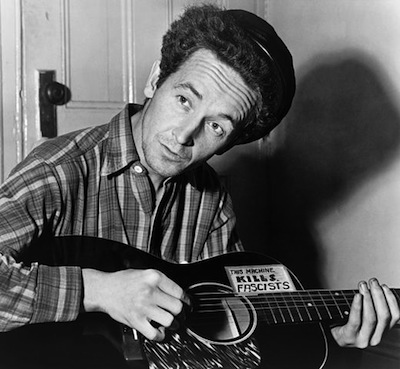

Woody Guthrie, March 8, 1943. Note the inscription on the guitar: "This machine kills fascists." Credit: Library of Congress

Woodrow Wilson Guthrie was born July 14, 1912, and the French Bastille Day was an appropriate birthday for an indigenous American radical who championed the revolutionary principles of liberty and equality on the other side of the Atlantic. Commemorations for Woody’s centennial are planned throughout the year, including the annual birthday musical festival in Woody’s hometown of Okemah, Oklahoma and culminating in a fall celebration in the nation’s capital. Academic conferences accompanied by musical artists honoring Woody have already been held at the University of Tulsa and University of Southern California with fall events scheduled for Penn State and Brooklyn College. But what exactly are we celebrating? Millions of school children, of course, know Woody through singing “This Land Is Your Land.” Yet, the more controversial verses of the populist anthem challenging private property are usually off the radar screen for school children. Guthrie’s indigenous radicalism, thus, has been somewhat neutralized in more recent years. But as we confront the greatest economic crisis since the Great Depression, which shaped Guthrie’s life and politics in the 1930s, we could use the ghost of Woody Guthrie who would likely be quite comfortable amongst the 99 percent protesters of Occupy Wall Street.

While a populist and man of the political left, Guthrie was never narrow and sectarian in his politics. Woody’s world view was influenced by Christian socialism, Jeffersonianism, populism, Eugene Debs, social banditry, Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, and communism. Woody perceived no fundamental contradiction between Marx and Jesus. After all, Jesus was the working-class carpenter who drove the money changers from the temple and taught that it was easier for a camel to fit through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven. Perhaps Guthrie’s indigenous radicalism is best captured in his concept of “commonism.” In the spring of 1941, he wrote in one of his voluminous journals, “When there shall be no want among you, because you’ll own everything in common. When the Rich will give up their goods into the poor. I believe in this way. I just can’t believe in any other way. This is the Christian way and it is already on a big part of the earth and it will come. To own everything in common. That’s what the Bible says. Common means all of us. This is pure old ‘commonism.’”

Guthrie’s path to “commonism” may be traced to his Oklahoma roots. During the first two decades of the twentieth century, the rugged Oklahoma environment nurtured a Socialist Party which prospered in areas where holiness sects opposed the materialism and modernism of society and the established churches. His father Charley, an outspoken opponent of the Socialist Party in the state, was a small-town entrepreneur whose investments never quite panned out, and the family’s fortunes declined. In addition, Woody’s older sister, Clara perished in a fire, and Charley was seriously burned in another incident. The behavior of Woody’s mother, Nora grew increasingly erratic, resulting in her institutionalization with a diagnosis of Huntington’s chorea, a degenerative disease of the central nervous system.

Charley and Woody eventually moved to live with relatives in Pampa, Texas, where Woody married Mary Jennings. He attempted to support a young family by painting signs, drawing pictures, telling fortunes, and playing music. However, the dust storms engulfing the Texas Panhandle made it difficult for anyone to earn a living. Leaving his family in Pampa, Woody joined the migration of “Dust Bowl refugees” to California. He settled with relatives in Glendale, and Woody soon teamed with Maxine Crossman, whom he called “Lefty Lou,” to form a popular duet on radio station KFVD in Los Angeles. Observing the terrible treatment which many of the Oklahoma migrants received in California, living under bridges and subject to the violence of vigilante men, Guthrie became increasingly politically active. He began to entertain workers in the fields during union organizing drives, and Woody wrote a column entitled “Woody Sez” for The People’s Daily World, the West Coast equivalent of The Daily Worker. Some observers believe that Woody joined the Communist Party during the late 1930s, although Guthrie biographers Joe Klein and Ed Cray disagree regarding the folksinger’s Party membership. Whether Woody actually joined the Party or not, there is little doubt that he lacked the self-discipline and demonstrated too much independence to be a loyal Party member. However, Woody certainly identified with the Party agenda of battling racial prejudice, fascism, and economic inequality during the 1930s.

In 1940, Woody made the odyssey to New York City, where he was lauded after a concert appearance on behalf of John Steinbeck’s Committee for Agricultural Workers. Alan Lomax, assistant director of the Archives of Folk Song at the Library of Congress, arranged for Woody to record his “Dust Bowl Ballads,” but Woody walked away from a commercial radio career that might curtail his political expression. Woody briefly found work in May 1941 with the Bonneville Power Administration, penning such songs as “Roll On, Columbia,” “The Grand Coulee Dam,” and “Pastures of Plenty,” promoting public power development. By the summer of 1940, Woody deposited Mary and the children in Texas, while he returned to New York City. He joined Pete Seeger and the Almanac Singers, supporting CIO organizing efforts and opposing American participation in World War II. Among the many songs he was writing, Guthrie penned “This Land Is Your Land” in response to what he considered to be the narrow parochial tone of Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America.” On a more personal level, Woody commenced a relationship with dancer Marjorie Greenblatt Mazia, which eventually culminated in the couple’s marriage.

Meanwhile, Guthrie committed to the Popular Front crusade against fascism after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. With recordings such as “The Reuben James,” Guthrie and the Almanac Singers advocated American participation in the war against fascism. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Guthrie traveled around New York City with the slogan “This machine kills fascists” scrawled on his guitar. He enlisted in the Merchant Marine, and in 1943 Woody completed his autobiography Bound for Glory, suggesting that not only Guthrie but the common people of America and the world were bound for the promised land.

In a series of passionate letters written to Marjorie while he was at sea, Woody perceived the Second World War as a grand crusade against fascism that would usher in a better world free from war, racism, exploitation, and poverty. On the home front, the fight against Jim Crow and the profit system was part of the international struggle against fascism. Woody, Marjorie, and the common people of the world were sacrificing to create a better tomorrow for their children.

Woody, however, was disappointed with the post-World War II reaction which produced the Cold War and McCarthyism, silencing reform by associating civil rights and the union movement with disloyalty and communism. Nevertheless, Woody threw himself into union organization and the struggle against Jim Crow. Woody had a tremendous potential for growth. His passion for social justice was initially stirred by the mistreatment and exploitation of his fellow migrants from Oklahoma, but in his music and political activism, Woody championed rights for black Americans and migrants from Mexico. For example, after reading about a 1948 California plane crash in which four crew members and twenty-eight “deportees” to Mexico were killed, Woody was incensed that newspaper accounts included the names of the crew while the Mexican laborers were simply referred to as deportees. In response, Woody wrote “Deportees,” which is often sung in concert today by his son, Arlo. He also recorded an album on the Sacco and Vanzetti case as well as Struggle, which included songs on the Ludlow Massacre and the “1913 Massacre” dealing with anti-union violence in Calumet, Michigan, for Moe Asch. Despite his history of leftist politics, he avoided the worst of the McCarthy reaction as he suffered through a series of personal tragedies. His daughter Cathy was killed in a fire on her fourth birthday, and Woody’s behavior became more erratic as his marriage to Marjorie deteriorated. It was discovered that Woody was suffering from the Huntington’s disease with which his mother was diagnosed. Woody was institutionalized in the mid-1950s until his death in 1967. As the ramifications of the disease intensified, his voice was stilled but not his influence as folk and protest music grew in the 1960s with artists such as Bob Dylan.

The music and life of Woody Guthrie continue to inspire. Woody was no saint. Although he could write beautiful love letters and songs extolling women such as “Union Maid,” he was often unfaithful in his relationships. In his life and music, Woody nevertheless exemplified a radical indigenous American who fought for social justice. Woody represents a rich radical American tradition which is all too often ignored by the textbooks. Woody has, however, resisted the efforts to deradicalize his legacy. Woody Guthrie continues to live in the hearts and minds of Americans who find inspiration in his life and music to struggle for a more just society for all people. Happy birthday, Woody!