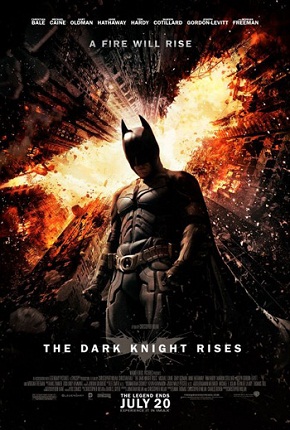

"The Dark Knight Rises" Elevates the 1 Percent and Trashes the Ninety-Nine

The tragic violence triggered by an apparently deranged lone gunman in Aurora, Colorado makes it difficult to write about the disturbing political implications of The Dark Knight Rises, the final chapter in the lucrative Batman trilogy from director Christopher Nolan and star Christian Bale. In addition to fostering heated debates over gun control, the mayhem unleashed in Aurora -- and most recently in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, where a white power skinhead punk rocker opened fire at a Sikh temple and killed six people -- will fuel concerns regarding the relationship between violence in popular culture and its all too real manifestation in the shootings at schools, theaters, churches, and temples. Nevertheless, The Dark Knight Rises raises some serious questions regarding the nature of American democracy and capitalism which are well worth pondering after we mourn the innocent victims slain at what should have been a festive midnight movie screening.

The tragic violence triggered by an apparently deranged lone gunman in Aurora, Colorado makes it difficult to write about the disturbing political implications of The Dark Knight Rises, the final chapter in the lucrative Batman trilogy from director Christopher Nolan and star Christian Bale. In addition to fostering heated debates over gun control, the mayhem unleashed in Aurora -- and most recently in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, where a white power skinhead punk rocker opened fire at a Sikh temple and killed six people -- will fuel concerns regarding the relationship between violence in popular culture and its all too real manifestation in the shootings at schools, theaters, churches, and temples. Nevertheless, The Dark Knight Rises raises some serious questions regarding the nature of American democracy and capitalism which are well worth pondering after we mourn the innocent victims slain at what should have been a festive midnight movie screening.

Nolan’s Batman films seem to provide serious reflections upon the political issues of the day and embrace an essentially conservative political ideology. For example, The Dark Knight (2008) may be interpreted as a commentary on terrorism, the number one threat to American stability until the financial meltdown of 2008. Heath Ledger's Joker, a villain upon whom the alleged Aurora gunman modeled himself with his orange-dyed hair (though in the movie and the comics, the Joker's hair is uniformly green), is a terrorist with no sympathy for his victims. To combat this evil, Batman (Christian Bale) resorts to vigilantism, while District Attorney Harvey Dent (Aaron Eckhart) maintains that in fighting crime, society must not succumb to the temptation of abandoning our fundamental liberties and principles in favor of security. However, when the Joker succeeds in murdering Dent’s beloved Rachel (Maggie Gyllenhaal), who also just happens to be the love interest of Batman/Bruce Wayne, Dent goes over to the dark side and goes after the people he holds responsible for her death, employing any means necessary -- including the attempted killing of Police Commissioner James Gordon (Gary Oldman) and his family. Batman intervenes and saves the day, but in the ensuing struggle Dent is killed. To assure that the memory of Dent as a courageous crime fighter is not compromised by the truth, Gordon and Batman agree that the Caped Crusader will assume the blame for Dent’s death and become a fugitive. Thus, the film may be read as a political allegory in which the policies of torture pursued by the Bush administration are necessary to combat the threat of terrorism. George W. Bush becomes the Dark Knight who is repudiated by the public, but whose actions have saved the nation, and at some point in the future his decisions will be understood by both historians and the general public.

***WARNING: SPOILERS BELOW***

The Dark Knight Rises picks up the story eight years later. The wealthy Bruce Wayne is a recluse and the Batman has disappeared. But there appears to be little need for Batman. The public revulsion against the murder of Dent resulted in popular support for restrictive laws placing the criminals in large prison network. The people have apparently chosen security over civil liberties.

A new threat emerges, however, when capitalist John Daggett (Ben Mendelsohn) -- who seeks to engineer a hostile takeover of Wayne Enterprises -- recruits master criminals Selina Kyle (Anne Hathaway) and Bane (Tom Hardy) -- and sorry Rush Limbaugh, Bane is not a left-wing Hollywood conspiracy to discredit Mitt Romney and Bain Capital. The original Bane character was introduced in Batman comics during the early 1990s. To save his financial empire, which also includes weapons of mass destruction designed by Lucius Fox (Morgan Freeman), Bruce Wayne re-enters the business world and forges an alliance with Miranda Tate, which eventually culminates in a love affair. Tate describes her youth growing up in poverty, but she has seemingly achieved the American Dream through ingenuity and hard work (although good looks do help). Combining the old wealth of the Wayne family with the rising business acumen of Tate represents the potential of moral and philanthropic capitalists to thwart the greed of corrupt Wall Street financiers such as Daggett. Thus, the film is hardly a condemnation of capitalism in the vein of documentarian Michael Moore. The 1 percent is comprised of both evil and benevolent components, defying simple class analysis. Rather than effective state regulation to control the forces of greed, The Dark Knight Rises puts its faith in the hands of a heroic individual capitalist Bruce Wayne and his alter ego Batman.

The film is more ambivalent in its treatment of the people, or the 99 percent, to borrow the language of the Occupy Wall Street movement. Bane murders Daggett and issues a call for social revolution, insisting that the people must be freed from the tyranny of the state and economic inequality. To gain the attention of the populace, Bane disrupts a football gladiatorial contest to introduce an atomic bomb, which will be detonated by any citizen attempting to flee Gotham City. Fearing the consequences, the president orders the army to isolate Gotham City, abandoning the city and its inhabitants. Meanwhile, the police force of the metropolis is trapped underground, and Bane calls upon the people to take this opportunity to liberate the many prisoners incarcerated under the punitive laws enacted in the wake of Harvey Dent’s death. In a scene reminiscent of the storming of the Bastille, the prisoners are freed (not by the 99 percent, admittedly, but by Bane's thugs), and a reign of terror ensues. Decent citizens cower in their homes, while outlaw elements roam the streets, and the property of the wealthy is seized by the poor, who seem every bit as greedy as the dead capitalist Daggett. Anyone opposing the tyranny is tried before tribunals in which rules of evidence are discarded in favor of revolutionary justice and penalties of death. At this point, the film draws its inspiration from a nightmare vision of the French Revolution with the Reign of Terror and Robespierre embodying the general will with the Law of Suspects. Bane even employs the rhetoric of the French Revolution, referring to the people as "citizens." Viewers may also equate this upheaval with the Russian Revolution, Soviet promises of an egalitarian society, and the terror of Stalin. Regardless of which historical parallel one may draw, The Dark Knight Rises suggests that violent opposition to the deeds of capitalists such as Daggett or contemporary Wall Street profiteers will only lead to destruction and greater injustice. According to the film, class warfare is not the answer. Instead, the people need a champion who will restore order and justice.

In this case, Bonaparte is Batman, who returns to battle Bane. He is aided by Selina Kyle, whose lower-class origins have left her with nothing but contempt for the wealthy whom she holds responsible for forcing to her to pursue a criminal career in order to survive. Kyle, however, is not poisoned by class hatred, and in the final analysis, she forms a class alliance with Batman to save the populace. The police are rescued from their subterranean prison and join the fray against Bane and his followers. In this regard, the local forces of order suggest the police and firemen who risked their lives while rushing to the rescue during 9/11. The film thus concludes that the people must place their trust in local officials rather than the power of a central government which has abandoned them.

The class politics of The Dark Knight Rises are further complicated when it is revealed that Miranda Tate is actually Talia al Ghul, the daughter of Ra’s al Ghul (Liam Neeson) from the first film in the Nolan trilogy, who seeks revenge against Batman and society for making the life of her family so miserable. Her mother was cast into a pit by her wealthy and powerful father for disobeying him and marrying Ra’s al Ghul. Talia is able to escape the pit with the assistance of Bane, who is disfigured for his efforts. Talia never forgives Batman for killing her father and detests the society of the pit in which her mother died and Bane suffered. She carries the scars from the pit with her, and she is unable to forget the past. But it is possible to escape the pit. Bane, who has assumed leadership of Ra’s al Ghul’s League of Shadows, casts Batman into its depths, but he is finally able to climb out when he eschews the safety net of a rope and relies upon his own abilities -- a perfect metaphor for the notion of the self-made man pulling himself up by his own bootstraps. The pit may be read as the cycle of poverty out of which many fail to escape, but the experiences of Talia and Batman suggest that it is not impossible; shifting responsibility for poverty to the individual rather than society. Escaping the pit has left Talia bitter and seeking revenge through class conflict. Batman, however, displays character and self-reliance which allow him to not be swallowed by the pit. He escapes to save Gotham City, and a reinvigorated Bruce Wayne demonstrates the possibilities of a philanthropist to make a difference in the lives of young people and help them elude the pitfalls of poverty.

When the smoke clears, Batman has retired from the fray, and the Bruce Wayne Foundation employs the power of capitalism to make the world a better place. It is impossible, however, to exorcise evil or greed from the world. The resignation of John “Robin” Blake (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) from the structure of the police force indicates that a new champion may be available if the people need him. And this film provides a most ambiguous message regarding the people in whose name all politicians in this electoral season seek to speak. Liberals assert that they will protect the people from corporate greed by assuring that safety nets are protected. Nevertheless, politicians on the left are often reluctant to discuss the growing poverty in the nation or even acknowledge the working class. Bowing to the conservative rhetoric that we must avoid class conflict at all costs, liberals focus upon protecting the amorphous middle class into which they lump all the people. Conservatives, on the other hand, assert that we must protect the job creators from excessive regulation and taxation so that they may provide the people with employment. Conservatives will also protect the common people from cultural elites who attempt to enforce their values upon the citizens. The people will be saved by the entrepreneur capitalist and protected by strict laws regarding crime and ideas which may challenge prevailing social norms.

The Dark Knight Rises and the Batman trilogy seem to embrace this conservative ideology as the people are essentially followers who rely upon others for direction. The film’s conclusion suggests that after the defeat of Bane and Talia, the people will be able to express their basic decency. The Bruce Wayne Foundation offers hope to some, but greed and evil remain along with poverty. And some will continue to seek shortcuts and corruption to escape the pit and use demagoguery to mislead the people. However, the possibility of a Batman to prevent social revolution while attacking both terrorists and greedy capitalists is supposed to offer reassurance. Yet, this reliance upon the promise of a powerful secular messiah is, indeed, a dark commentary on the promise of American democracy and social justice.