Paul Ryan's Hijacking of Natural Rights

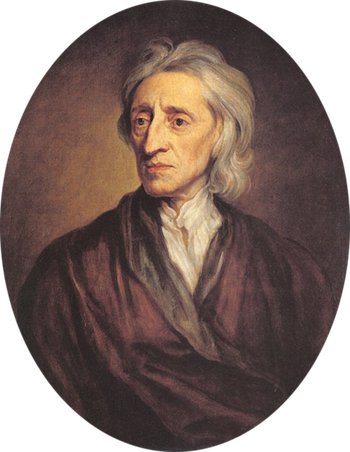

Portrait of John Locke, by Sir Godfrey Kneller, 1697.

Surely one of the great ironies of American history is that the use of the word Creator in the Declaration of Independence has become the basis for arguing that the document, and the laws of Nature that it reveres, are particularly Christian in their origin.

Surely one of the great ironies of American history is that the use of the word Creator in the Declaration of Independence has become the basis for arguing that the document, and the laws of Nature that it reveres, are particularly Christian in their origin.

A more straightforward challenge to history is the current use of John Locke in sound bites and speeches, where he becomes the champion of absolute, God-given rights but not of the power of experience to shape and transform lives.

Though both John Locke and the Declaration in fact combine a reverence for rights with the dynamism of nature and experience, Paul Ryan, the presumptive vice-presidential nominee of the Republican Party, is in the vanguard of extreme conservatives who want Americans to believe that both natural law and natural rights are ordained by the God of Biblical revelation.

This disdain for experience (one might also say for evolution) serves only to denature nature's law, and to ground both natural law and natural rights in emotion and static dogma.

When Paul Ryan says the 2012 presidential election is about "natural rights" versus "government rights," he wants us to believe that natural rights are from the Christian God and therefore absolute, and that government rights, i.e., those enacted laws and court rulings that are assumed to be contrary to God-given rights, are not only illegal but are an affront to God. Such a notion is especially appealing when the natural right deemed to be sanctified has something to do with private property or taxes.

On the issues of same-sex marriage and abortion, Ryan points to natural law and natural rights as the source of opposition to both, with Ryan's position reflecting those of the Catholic Church as an institution (though not of many Catholics) and of the "New Natural Law" arguments of conservative Catholic intellectuals, such as Robert George of Princeton.

The New Natural Law is an attempt to use non-sectarian proxies for what St. Thomas Aquinas identified as natural moral "goods" (things eternally good in themselves) derived from Church teachings. But rather than enlarging on the older, sectarian natural law arguments of St. Thomas about what constitutes moral goods, the goods identified by the new natural law proponents (especially Robert George's Oxford mentor, John Finnis) also require the condemnation of contraception along with certain sexual behaviors, including oral and anal sex, and masturbation. Readers can judge how practical this reasoning may be.

St. Thomas has been rightly honored as an intellectual giant, and in the thirteenth century he seemed to demonstrate that natural law was human reason in the service of the eternal laws of God. With those laws as the premise, reason could then with considerable effort deduce their relation to the world, and identify certain rights as being compatible with the eternal laws. In this way, the ought of human conduct as set forth by the Church determined the is of worldly behavior

Such a view could prevail in the thirteenth century and beyond, so long as the world remained sufficiently mysterious to deny a more specific understanding of what the world is.

Yet even Thomas's natural law was more enlightened than the New Natural Law, for Thomas identified the supreme moral principle as being something very like the Golden Rule: "one should love one's neighbor as oneself." The essence of natural law as understood by Locke and others also assumed that rational self-interest would lead to a willing sacrifice of some rights to the common good in order to retain as many individual rights as practicable.

By the time of the Declaration of Independence, the leading Founders were men of the Enlightenment, and for them, according to the late historian Carl Becker, the relation of man to the world, and of both to God, had changed dramatically.

In his lecture "The Laws of Nature and of Nature's God," published as part of the book The Heavenly City of the Eighteenth-Century Philosophers, Becker wrote that to "find a proper title for this lecture I had only to think of the Declaration of Independence," about which he wrote another famous study. With remarkable style and insight, Becker analyzed the shift from the natural law position of St. Thomas to that of the men of the Enlightenment, including most of the prominent Founders.

It was primarily the work of Sir Isaac Newton in the previous century that allowed eighteenth-century intellectuals to regard ultimate reality and natural law as "self-evident" from the human observation of nature, and no longer requiring the elaborate "construction of deductive logic" to connect God to nature, as in the era of St. Thomas. Newton himself believed he had done no disservice to God in formulating a universal law of gravity, and believed he had enlarged man's understanding of God by demonstrating the rational and accessible character of God and the universe God had created.

This brings us to the Creator designated as the source of rights in the Declaration of Independence. The inalienable rights from this Creator are not derived from the tortuous reconciliation of religious dogma to the world; instead they are "self-evident" in nature, in His universal laws of nature, as nature is. And, as Becker explained, this Creator, this "Nature's God," was not a disquieting prospect for most people at the time.

"Christian, deist, atheist -- all acknowledged the authority of the book of nature; if they differ it is only as to the scope of the authority, as to whether it merely confirms or entirely supplants the authority of the old Revelation." But, he added, "nature is [in the late eighteenth century] the true test, the standard."

Finding these laws in this "book of nature" is an empirical process -- Newton said the purpose of what he called "natural philosophy" was "to search into Things themselves." Our understanding of these laws, then, is not static but progressive.

Paul Ryan disparages a "progressive" understanding of the Constitution as a violation of natural rights, as he sees them. Like Justice Anthony Scalia and many other conservatives, he wants an unchanging and absolute system of morality to be the appropriate basis for a system of laws, though what they both see as moral demonstrates the emotional or subjective influence that often accompanies Constitutional analyses under the distorted view of natural law.

Their views bring to mind the words of Justice Holmes, whose distrust of this use of natural law is well known. "Certitude is not the test of certainty," Holmes wrote. "We have been cocksure of many things that were not so." Holmes knew what the classical skeptics knew: certainty looks for tested truth, while certitude looks for what we want or need to believe.

Paul Ryan, having read Ayn Rand, evidently needs to believe that her deification of radical self-interest can co-exist with his archaic idea of natural law and natural rights, never mind her amorality. His view of natural rights also elevates the liberty rights of individuals far above those of the community and gives them the sanction of God, in order that some individuals may become all the more outraged if those rights appear to be transgressed.

Above, we discussed the Declaration of Independence; now on to the Constitution, created to counter the embarrassing effects of the failed Articles of Confederation, in which states' rights were paramount. The preamble to the Constitution, without mention of either God or natural law, uses language that respects the mutual relationship of rights and the common good envisioned by the Founders and the natural law of their time, and expressed in both the Declaration and the Constitution:

"We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America."

In the context of the current campaign, it seems necessary that the emphases be added.

Related Links