A Lesson in Volunteerism from George Romney

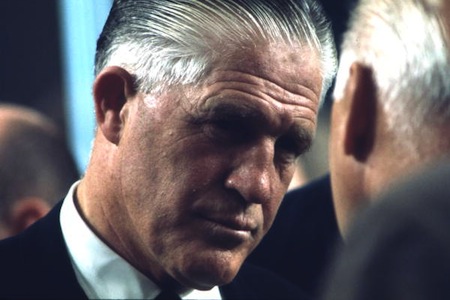

George Romney at the 1968 Republican National Convention. Credit: Florida Memory Project

Mitt Romney might learn an important lesson from his father.

Mitt Romney might learn an important lesson from his father.

While the rhetoric of the Republican National Convention repeatedly exalted the promise and power of the individual -- and the threat of an enterprise-stifling government -- the Republican nominee’s campaign agenda is silent on an issue that was central to the governmental vision of his late father.

George Romney was a fervent advocate of voluntarism. A devotee of voluntary action advocate Richard Cornuelle and a veteran of Citizens for Michigan, a non-government organization that successfully reformed Michigan’s outdated constitution in the early 1960s, Romney believed that voluntary citizens’ organizations could meet local needs, contribute to state and national debates and create solutions that would remedy the many problems facing the nation in the late '60s and early '70s.

The elder Romney put this belief into action, becoming a leader in what grew to include a number of efforts across the United States to develop organizations that would stimulate independent leadership efforts, cross-partisan cooperation and voluntary service among business and community leaders and others in a position to contribute the lessons of experience to the wider society.

In 1969, for example, the Nixon administration established a Cabinet Committee on Voluntary Action, led by then Housing and Urban Development secretary Romney. The committee’s service arm, the Office of Voluntary Action, conducted a nationwide survey of volunteer resources and potential. The OVA concluded that despite the vast number of government and private agencies geared toward public service, there was a need for a non-governmental structure at a national level to serve as a clearinghouse for interests, resources and programs. Accordingly, the OVA formed a National Center for Voluntary Action in February 1970 to meet this need.

Operation of this gargantuan effort was far from flawless, and the organization’s leadership went through several changes, but Romney’s commitment to the NCVA and what it stood for was apparent. As he left his HUD post in late 1972, Romney contemplated taking the chairmanship of the NCVA. While ultimately he opted against this move, he did so in favor of forging a new, related organization that would bring together what he’d long referred to as the “concerned citizens” of America.

Romney’s Concerned Citizens Movement evoked a tremendous response from Americans across the country as news of the embryonic organization spread. Reams of files bear witness to the thousands of “concerned citizens” whose imaginations were captured by a vision bringing Americans from all walks of life and various political persuasions together to debate the “life or death” issues of the time. Romney’s hope was that by involving community leaders from a wide variety of professions and with myriad ideological backgrounds, Concerned Citizens could develop policy solutions that would generate lasting change in the United States. His commitment to pluralism was clear. Romney aides carefully crafted lists of potential supporters identified as conservative, moderate or liberal, Democratic or Republican, tallying their figures to ensure representation.

Ultimately, the promise of Concerned Citizens foundered under the burdens of a lack of specificity and the pressures of the Watergate era. “Life or death issues” proved a platform too broad for efficient organization, and the uncertain political environment surrounding Watergate made long-term mobilization difficult. More significant, however, was what Concerned Citizens and the NCVA reveal about the elder Romney’s motivations.

George Romney was skeptical about the efficacy of a large federal government. His skepticism about excessive power extended beyond government, however, to encompass big labor and even big business. In 1958, for example, the then-American Motors chief executive testified before Congress that he believed the Big Three automotive manufacturers should be required to split apart, improving competition and therefore opportunities for innovation that he believed had been stifled by excessive concentration. His belief in voluntarism comprised an important part of this worldview.

For Romney, society functioned best with less concentration in all sectors. By replacing the top-down mandates of government, business or labor with citizen activism across society, he believed the United States could surmount the problems of his day and forge a more innovative future.

Mitt Romney and his party have fervently advocated for reductions in government. Where, however, is the equivalent call to service? How would the GOP stimulate a climate of shared responsibility? Free enterprise might play a role, and supporters of the younger Romney would likely point toward this solution. For the elder Romney, however, business composed one important part of a much larger whole. Republicans need a culture of support for voluntary networks like that his father advocated if they’re to adequately address the important social problems of our day, and at present Mitt Romney’s campaign seems lacking in this respect.

Related Links