The Bad Things Presidents and Would-Be Presidents Have Said About Each Other

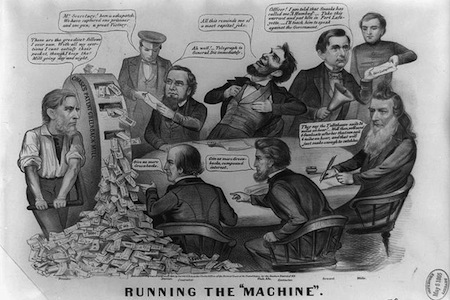

Anti-Lincoln political cartoon from 1864 by John Cameron, printed by Currier and Ives. Credit: Library of Congress.

Recently I went to a dinner party at which several guests wondered aloud if the 2012 presidential election was setting some sort of record for nastiness. The two candidates and their spokesmen were calling each other a startling range of names from liar to crook to weakling to would be dictator. I agreed that the rancor was growing intense -- but I assured them that other candidates for and holders of the nation’s highest office had compiled a record that equaled and often exceeded the current epithets.

Recently I went to a dinner party at which several guests wondered aloud if the 2012 presidential election was setting some sort of record for nastiness. The two candidates and their spokesmen were calling each other a startling range of names from liar to crook to weakling to would be dictator. I agreed that the rancor was growing intense -- but I assured them that other candidates for and holders of the nation’s highest office had compiled a record that equaled and often exceeded the current epithets.

Enraged by President George Washington’s refusal to support the French Revolution, Thomas Jefferson said he was "a Samson who had allowed himself to be shorn by the harlot, England." Around the same time, an ardent Jefferson supporter, journalist James Thomson Callender, offered a toast at a public dinner "to the speedy death of President Washington."

A few years later, President John Adams, defeated for re-election by Mr. Jefferson, accused him of having "a mean thirst for popularity, an inordinate ambition and a want of sincerity." Adams shuddered at "the calamities" that Jefferson’s policies would soon inflict on the country.

During the War of 1812, opposition journalists sneeringly called diminutive President James Madison "Little Jemmy" and openly speculated that he persuaded Congress to do his bidding by granting prominent solons access to his buxom wife, Dolley. Aaron Burr, who served a term as Jefferson’s vice president, said President James Monroe was so dimwitted, in his days as a lawyer he had never won a case that paid more than $5.00.

John Adams’s son, John Quincy, said Andrew Jackson, who defeated him for re-election in 1828, was "a barbarian who can barely sign his name." Jackson’s successor, Martin Van Buren, was a player of "base and dirty tricks."

When President James Polk went to war with Mexico, Congressman Abraham Lincoln of Illinois said the conflict was "unnecessarily and unconstitutionally commenced." Lincoln added that he was sure Polk was "deeply conscious of being in the wrong." In short, he was a complete hypocrite.

When the Civil War exploded in 1861, ex-presidents Millard Fillmore and Franklin Pierce attacked Lincoln as a war monger and would-be dictator. Pierce was particularly vehement. He found fault with almost everything Lincoln did, calling one of his early decisions "an idle, foolish, ill-advised, if not criminal thing."

Bad as this is, it does not approach the nickname New Jersey Democrats fastened on Abe -- "the brainless bob-o-link of the prairies."

President James Garfield remarked that he could never decide whether President Ulysses Grant’s imperturbability was proof of his greatness or his stupidity. Grant returned this compliment with interest. He said Garfield "lacked the backbone of an angleworm."

During the 1912 presidential campaign, Theodore Roosevelt, running on a third-party Progressive ticket, called President William Howard Taft a "puzzlewit" and a "fathead." Taft called Teddy, once his best friend, an "egotist" and a "demagogue." Roosevelt seemed unbothered by these exchanges but one reporter told of finding Taft, after a speech damning Roosevelt, slumped with his head in his hands, weeping.

Teddy only succeeded handing the presidency over to the 1912 Democratic candidate, Woodrow Wilson. They soon clashed in spectacular fashion over whether America should enter World War I as an ally of Britain and France. Infuriated by college professor Wilson’s elaborate and evasive speeches, Teddy called him "a Byzantine logothete." That was a Harvard man’s way of saying that the president talked and talked but never got to the point.

Wilson’s opinion of his successor, Warren Harding, was terse and totally negative. He was "a fool of a president." Harry Truman predicted Dwight Eisenhower would make Ulysses S. Grant’s scandal-scarred administration look like "a model of perfection." Truman had an even harsher opinion of Lyndon Johnson: "No guts." He thought Johnson should have run for re-election in 1968. "Instead he let a mob of anti-war protestors run him out of the White House."

John F. Kennedy called Richard Nixon "a filthy lying son of a bitch and a very dangerous man." Lyndon Johnson was even more harsh -- and prophetic. "He’s like a Spanish horse, who runs faster than anyone for the first nine lengths, and then turns around and runs backwards." Johnson was equally merciless to Nixon’s successor, Gerald Ford. "Jerry spent too much time playing football without a helmet."

Maybe there’s something about being president or thinking about being president that ignites tempers and loosens tongues. Maybe it would also be helpful to know that many of these nasty remarks were later retracted or forgotten. In later years, John Adams exchanged dozens of friendly letters with Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt became reconciled with William Howard Taft and Harry Truman resumed cordial relations with Dwight Eisenhower. In 2024 or 2025 will we hear similar news about Barack Obama and Mitt Romney?