How Mormons and African Americans Criss-Crossed Political Identities

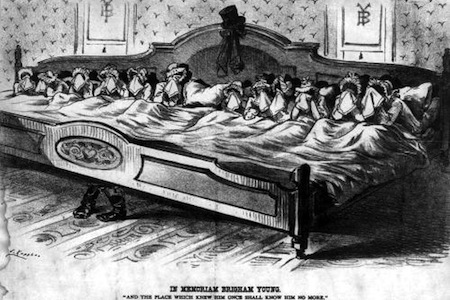

Political cartoon from Puck, 1877.

The 2012 election is marked by a paradox common to politics across much of the globe. Partisans invoke, appeal to, and claim to embody national unity and the public good as they engage in a divisive power struggle. Whether we view the current slate of candidates as conflicted, manipulative, or both, they hardly stand out for celebrating their country as a community in one breath while positioning their opponents on the outskirts in the next.

The 2012 presidential election has, however, added an ironic twist to this paradox. Democrats and Republicans have been squaring off against each other since the 1850s. Today, however, both parties are led by members of groups that they once excelled at marginalizing. The Democrats of 1856 were largely unabashed white supremacists who impugned their rivals as “black Republicans” because they were willing to criticize and then help destroy Southern slavery. When the Republican Party legislated a dramatic expansion of African-American rights during Reconstruction, the Democratic Party played the role of obstructionist in federal politics while its paramilitary surrogates terrorized African Americans in the South. Virulent racism helped define the Democratic Party from the mid-nineteenth century into the mid-twentieth, when the party haltingly changed course in part to court increasingly numerous African Americans voters in the North and West. After the Democrats supported the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act in the 1960s, Richard Nixon lured disgruntled white supremacists in the South and elsewhere over to the Republican Party. Much of the oft-veiled racist rhetoric of the Republican Party today is derivative of stereotypes first peddled by Democrats.

The Latter-day Saints, with important exceptions including Harry Reid, came into the Republican fold through another set of historical twists and turns. The founding generation of the Republican Party viewed Mormon society in the Utah Territory as the moral equivalent, if not the mirror image, of the slaveholders’ society in the South. Republicans were adamant opponents of the political power of the Mormon Church within Utah and often described the territory as under the control of a "theocratic despotism." Brigham Young and his associates, most Republicans believed, sought to rule vast stretches of the western United States as their personal kingdom. A lust for unchecked power, so the argument went, motivated the Mormon leadership just as it did domineering Southern aristocrats eager to protect and expand slavery. The same premise led Republicans to describe the Mormon practice of celestial marriage, more commonly referred to as polygamy, as akin to Southern slavery -- or as the 1856 Republican platform put it, the two were “twin relics of barbarism.” Immersed in a culture deeply concerned with the relationships between men, women, and children, Republicans viewed slavery and polygamy as sexual institutions that allowed men to indulge their desires without restraint. It was only after the Mormon Church renounced polygamy in 1890, after nearly three decades of Republican pressure, that Utah gained statehood and, later still, became a Republican stronghold.

The Republican Party had the upper hand in federal politics during much of the thirty years following the Civil War. Had it not, African Americans might still lack the right to vote and Mormons might still practice polygamy. Precisely because this claim seems outlandish in today’s political context it serves as a healthy reminder. The electoral process in the United States forces political parties -- or at least the nationally competitive ones -- to exist as uneasy coalitions. In a winner-take-all system, interest groups have to form alliances before elections if they want their candidates to hold office. American political parties are in a nearly perpetual state of redefinition as they search for compromises among factions and enough common ground to present a united image to the public. Often, political parties find it easier to explain what they are not than what they are. Even here, however, substance and image change over time. In the late nineteenth century, when Republican politicians and writers referred to Muslims it was often to condemn Mormons, who they regularly slandered as “Turks.” Given how frequently political parties in the United States refashion themselves it should be unsurprising that most African Americans and Mormons have changed their allegiances over a few generations. What is more surprising is that so many people in the United States invest so much meaning in their party affiliations. Then again, the same thing could be said of their national identity, which is every bit as fluid and contested.