Presidential “Czars”: A Constitutional Aberration

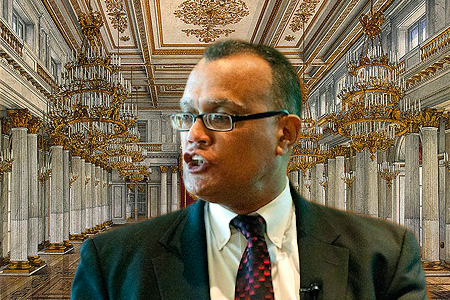

Ed Montgomery, Obama's auto bailout czar (official title: Member Presidential Task Force on the Auto Industry, Director of Recovery for Auto Communities and Workers) in 2010. Credit: Flickr/pennstatelive/HNN staff.

The problems that President Barack Obama inherited when he took office -- two wars abroad, and at home an economic crisis with possible collapse of the auto industry, meltdown of the banking sector and housing market -- generated expectations that he would take resolute action. During actual and perceived crises, there is little sentiment to constrain a president’s powers. Obama acted quickly and, among other actions, he put into place a number of officials who could assist in responding to crises by coordinating policy responses within the executive branch. Some of those officials are commonly referred to as “czars” and they have become controversial given that they are in unconfirmed positions and yet exercise considerable policy, regulatory and spending powers.

The problems that President Barack Obama inherited when he took office -- two wars abroad, and at home an economic crisis with possible collapse of the auto industry, meltdown of the banking sector and housing market -- generated expectations that he would take resolute action. During actual and perceived crises, there is little sentiment to constrain a president’s powers. Obama acted quickly and, among other actions, he put into place a number of officials who could assist in responding to crises by coordinating policy responses within the executive branch. Some of those officials are commonly referred to as “czars” and they have become controversial given that they are in unconfirmed positions and yet exercise considerable policy, regulatory and spending powers.

The role of czars has come under congressional and public scrutiny, as these officers are not subject to Senate confirmation and they operate outside the normal constraints of the system of separated powers. At one point, President Barack Obama’s White House counsel informed protesting Senators that various executive branch czars would not be permitted to testify on Capitol Hill, as these officials are not equivalent to Cabinet secretaries in their functions.

The role of czars is significant because governing power comes not just from assigned duties but also from proximity to the President. Czars exist outside the system of accountability and they have potentially enormous influence on setting the national agenda in a variety of areas. Unconfirmed officials are not merely influencing, but oftentimes directing policies and making spending and regulatory decisions within executive branch agencies and departments.

Although in the past they were relatively obscure, executive branch czars have become flash points of a heated political and constitutional debate in the Barack Obama era. One reason is that some prominent conservative pundits, especially Glenn Beck and Rush Limbaugh, have taken up the issue and brought substantial attention to the controversial role of czars.

To be fair, the use of czars is not new to the Obama administration. President George W. Bush appointed numerous czars with little protest from conservative opinion leaders. But the current administration has added an extraordinary number of new czar positions and then announced that many of these executive branch officials are walled off from Congress.

Advocates of the use of czars maintain that these officials usually have merely advisory roles in the White House and that most do not exercise any controlling legal authority. Thus, from this standpoint, czars do not appear to violate principles of governmental transparency and accountability. The Obama White House has stated that czars do not supplant or replace the authority of existing federal departments and agencies; rather, czars coordinate the efforts of many governmental units to provide for comprehensive planning and decision-making.

The Obama White House maintains that the enormity of many of the issues it has confronted –– from the financial crisis, to the U.S. auto industry collapse, to global climate change, among others –– requires the appointments of figures to coordinate government responses across numerous departments and agencies. Furthermore, few would dispute that presidents need and are entitled to have the assistance of some trusted confidential advisers, and the president relies on his White House czars, among others, to fulfill that function.

Disputes about the role of White House aides predate the creation of czars and indeed are as old as the Republic itself. The U.S. system has always recognized that presidents need help to carry out their duties, and even George Washington had a cabinet with four secretaries and six staffers. The first president dealt with a number of disputes over the right of White House and cabinet secretaries to maintain confidentiality, their policy roles, and the president’s removal powers, among others.

The constitutional design of the president’s help was shared between the executive branch and the legislative branch. The president should not unilaterally determine executive branch staffing; both the Appointments Clause and the “lesser officers” provision of the Constitution demonstrate the contrary. Furthermore, the absolute authority of the legislative branch to control funding for the executive staff suggests that presidents should have limited control over the form of help that they receive in the White House. All White House aides should be answerable ultimately to Congress.

The trouble is that, over time, as the system moved away from one of legalistic constraints to one of power personalized and often concentrated in the presidency, White House aides came to see their roles as advocates of the president oftentimes against the will of Congress. White House aides have their primary loyalty not to congressional programs and statutory missions but to what they see as the "mandate" from the president's election.

These presidential aides are not merely advisers, but they now have the capacity to change the power balance between the branches and have played a role in moving the federal government from a legal system to a more personalized (presidential) one. Thus, critics of czars raise an important question: What effect do these unconfirmed executive branch officials have on the American constitutional system, which is premised on popular control operating through statutes enacted by elected members of Congress?

If czars are involved in operations and implementation, the congressional effort to set up a legal/accountable structure -- using statutes to create agencies and their programs and confirming the top officials -- is undermined by these unconfirmed presidential appointees. This capacity of executive branch officials to operate outside the system of accountability has led to significant constitutional conflicts in the past, notably, for example, the Iran-Contra scandal during the Reagan era.

The role of czars poses a serious set of constitutional issues. The U.S. Constitution specified a system of accountability, with Congress having the power to enable the functions and funding of executive branch offices. Yet czars create a special dilemma in that they are not subject to confirmation by the Senate, they lack any statutorily created duties, and in many cases in the Obama White House they appear to be supplanting the roles of confirmed Cabinet secretaries. They give policy advice to the president and even make important decisions, but he will not allow many of them to testify before Congress.

Presidents need confidential policy advisers and President Obama relies upon the judgments of a number of his White House czars. To the defenders of czars, the enormity of many contemporary policy problems validates the need for some system of coordination among various departments and agencies. In this regard, czars appear to have a beneficial impact on the policy system.

Nonetheless, just because newly created offices have utility does not render them constitutionally proper. Czars ultimately violate the constitutional principle of separation of powers and democratic accountability.