Why Has Mormonism Been Such a Non-Issue in This Election?

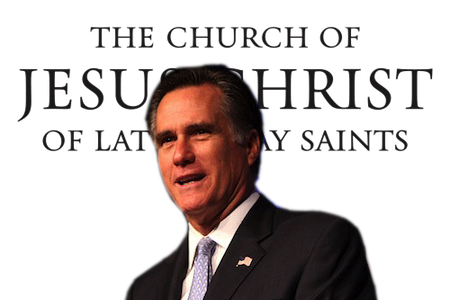

Credit: Wikimedia Commons/HNN staff.

Religion has long been one of the most powerful and divisive issues in politics in the United States. Even a highlight reel of religion’s history of entanglement with local, state, and federal political contests would be lengthy. Since the early years of the republic, politicos have appealed to religious identities and stereotypes for electoral gain -- a tradition exemplified, for instance, by the Republican Party’s anti-Catholicism during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Similarly, political disputes have often seeped into denominational histories, sometimes strikingly so, as with the rupturing of the Presbyterian, Methodist, and Baptist churches over slaveholding in the 1830s and 1840s. Considered in this light, what stands out about the 2012 election is that public conversation about Mitt Romney’s membership in and devotion to the Church of Latter-day Saints has been so modest. It is hard to imagine political rivals -- or at least their surrogates -- from the 1800s, 1850s, 1920s, or perhaps even the 1960s holding back from the opportunity to marshal popular attitudes about religious minorities to their advantage. So why have broad-based discussions about Mormonism in this election been, compared to the long arc of American history, limited in volume and, with exceptions, moderate in tone? Several reasons come to mind that remind us of the complexity of political and ideological life in the United States.

The first reason for the paucity of public discussion is that the Republican Party and the Romney campaign have little incentive to draw attention to Romney’s faith as a Mormon. Due to the winner-take-all election system, successful political parties in the United States are usually coalitions. In the case of the Republican Party, the coalition includes socially conservative evangelical Christians, some of whom described the LDS Church as a "cult" during the primaries. Since turnout will be crucial to the election, the Romney campaign has to play up Romney’s religiosity without accentuating his Mormon-ness, or risk ambivalence among some supporters.

Second, the leadership of the LDS Church may also prefer public reticence. While it is tempting to assume that a minority religion would welcome the attention and prestige that comes with one of its members competing for high office, Romney’s campaign entails some more complex implications. One issue is that Romney’s clean-cut image does little to advance the Church’s public relations campaign against popular stereotypes of LDS members as uniformly simple and plain. One of the Church’s initiatives has been its “I’m a Mormon” website, which includes well-produced videos featuring Mormons discussing their lives and faith. “... our backgrounds and experiences are diverse,” notes the first sentence of the webpage’s opening paragraph.

Third, Democratic politicos probably worry that raising the issue of Romney’s religion risks feeding into another stereotype -- that Democrats are a bunch of secularists and post-Christian spiritualists who equate doctrinal Christianity with intolerance and intellectual backwardness. Paradoxically, the theological disagreements that divide Mormons from Baptists and other evangelicals also unite them against a figurative non-believing Democrat. Since at least the 1970s, Democratic candidates have had to struggle with the image of their party as arrayed against the beliefs and politics of large swathes of self-identifying Christian voters. In this context, Democratic commentary about Romney’s faith could backfire, alienating religious independents and firing pro-Republican evangelicals to turn out for Romney.

A fourth reason lies with the emphases on political correctness and religious toleration that shape, however unevenly and inconsistently, public life in the United States. Where prejudicial scorn for and inaccurate characterizations of marginalized groups once found ready expression, an overt if not always sincere sensitivity about identity and difference currently prevails. Claims about the dispositions and values of specific groups of people now risk considerable political liabilities. Related but more diffuse is the anxiety that often attends public discussions about race, religion, and a host of other issues. More so than in the past, being accused of bigotry, ignorance, or intolerance brings with it stigma, and Democrats and Republicans may prefer to avoid conversations that risk generalizing about Mormons and the LDS Church.

Finally, it may be that positive and negative stereotypes of Mormons have become so pervasive and contradictory that many feel uncertain about where conversation should begin. Though references to Mormons and the LDS Church are commonplace in American culture, these only occasionally reflect or provide knowledge of the intricacies of Mormon belief or thoughtful perspective about the relationship between faith and politics. It is hard to start a serious discussion of a presidential candidate’s religion with a question about magical underwear. Of course, for much of American political history, discussions of religion were hardly marked by a quest for mutual understanding. Arguably, however, the changes addressed in the preceding point did create more space for sustained deliberation, even if that space still requires careful navigation.

Related Links