Does Slavery Still Exist Today?

Credit: Flickr/Inheritance magazine.

New Year's Day 2013 marked the sesquicentennial of the Emancipation Proclamation, an executive order that freed slaves under Confederate control and a major step toward the December 1865 adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment, which outlawed slavery and involuntary servitude (except for convicted criminals) in the entire United States and its territories. Hundreds of historians are “celebrating” that anniversary by joining Historians Against Slavery (HAS), a recently established non-profit organization that seeks to improve understanding of historical forms of slavery in order to help activists to decrease the number, and ameliorate the conditions, of people enslaved in various ways around the world today.

New Year's Day 2013 marked the sesquicentennial of the Emancipation Proclamation, an executive order that freed slaves under Confederate control and a major step toward the December 1865 adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment, which outlawed slavery and involuntary servitude (except for convicted criminals) in the entire United States and its territories. Hundreds of historians are “celebrating” that anniversary by joining Historians Against Slavery (HAS), a recently established non-profit organization that seeks to improve understanding of historical forms of slavery in order to help activists to decrease the number, and ameliorate the conditions, of people enslaved in various ways around the world today.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, millions of chattel slaves and serfs managed to release themselves from the physical and legal shackles that had defined their condition but emancipation was nowhere complete. In Haiti, a system of childhood slavery developed and persists to this day. On the Asian steppe, former serfs and their progeny fell victim to pogroms, war, and enslavement by the state. In America, many freedpersons and their descendants, along with many poor whites, became debt peons virtually enslaved to their creditors (think Tennessee Ernie Ford’s “Sixteen Tons”) or wound up laboring for the benefit of others for years in prison (think Lucas Jackson in Cool Hand Luke and Andy Dufresne in Shawshank Redemption).

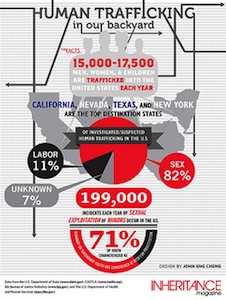

Although chattel slavery has been legally abolished, people in some parts of the world are still kidnapped, transported abroad, and sold to employers for whom they are forced to labor mightily for no more than their bare subsistence. Their stories, as revealed in the recent State Department documentary Journey to Freedom, are uncannily similar to the American slave narratives of Frederick Douglass and Solomon Northrop. Numerous other forms of unfree labor also persist, including involuntary servitude, bonded labor, sex trafficking, and forced child labor. Millions of people worldwide are coerced and brutally exploited, including many here in the United States, in an illegal but thriving sex trade, the gray market for unskilled immigrant workers, or an increasingly corporatized penal system with off the charts rates of incarceration.

So one hundred fifty years on, the legal abolition of chattel slavery no longer looks like a telling victory in some grand, progressive war against oppression but rather a minor skirmish that, while thankfully won, did little to change humanity’s basic inhumanity (recall Freud’s Homo homini lupus). But while history shows that slavery is ancient (see, for example, Leviticus 25:44-46), economics teaches that the quantity of people enslaved can be reduced by decreasing the supply of potential slaves and/or the demand for slaves.

Many activists work on the supply side by aiding those most vulnerable to enslavement, particularly children, women, the poor, and the unskilled and uneducated. It’s important work that helps many but so long as most of the world’s population remains impoverished, undereducated, and subject to governments ranging from inept to outright predatory, the supply of potential victims will remain large.

The demand side is more manageable because employers typically use the type of labor that they believe is the most profitable given their specific circumstances. To reduce the demand for slaves, therefore, governments, businesses, and consumers must raise the total cost of the use of bound laborers. Employers that cross the line into illegality need to suffer big fines and significant imprisonment. Those who treat their workers harshly but legally need to be shunned socially and introduced to more enlightened management practices, which appear costly until productivity improves along with worker morale and turnover.

Business owners also need to inform slavers that “freedom” is not just ideological cover for deregulation, it is a human right that, in addition to being invaluable in and of itself, helps to drive economic growth. Slavery anywhere, in other words, decreases growth everywhere. Demand for slaves can also be reduced by increasing the attractiveness of alternatives by improving the mobility of wage labor or encouraging automation. Chattel slavery ebbed in the northern states because abolitionists raised the psychological costs of owning slaves and laid bare slavery’s detrimental effects on economic development while immigrants and rural emigrants filled the North’s early factories.

Corporate leaders today need to become active abolitionists because the slavery reparations movement of the 1990s and early 2000s is still alive and in a more virulent form. Blaming corporations for wrongs committed long ago (that were not technically crimes when committed) had little chance of success politically or legally. Lawsuits based on contemporary oppressive labor practices, whether perpetrated directly and domestically or overseas at the end of a long but known (or knowable) supply chain, are a different story. Around the world, awareness of coercive labor practices is rising and there is no telling when or how it will end, especially when taxpaying voters begin to learn about the extra costs they bear to support systems of slave production and distribution. It’s time to join Adam Smith, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, Hinton Helper, John Pepper (former CEO of P&G), and thousands of business leaders who voluntarily emancipated their slaves on the right side, not of history, but of economics and business management.