Why the Business Community and the GOP Base are Parting Ways on Immigration

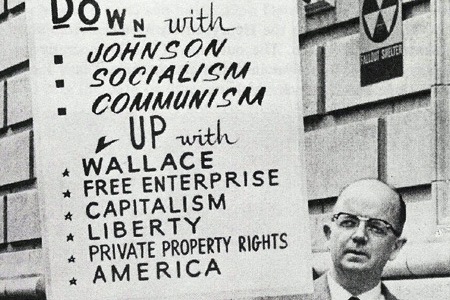

Lester Maddox, future governor of Georgia, picketing in Atlanta in 1965.

Policymakers overhauling American immigration reform have recently turned to a seemingly unlikely set of allies: business owners. Many executives have kept their labor costs down by employing illegal immigrants but directors are still showing themselves open to legislative change. “This is not a fight that’s going to be won in Washington,” one of New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg’s advisors explained, “It’s going to be won in districts across the country as representatives hear from local business owners, from local chambers of commerce, from job creators at home, all saying that passing immigration legislation is crucial to the success of their local economy.” Republican John McCain proclaimed “small business, large business, the chamber, the Business Roundtable, you name it, they’re all solidly” behind his proposed legislation. “We need them to weigh in on this issue,” he explained, “because we advertise ourselves as the party of business.” The senator had reason to have faith in his entrepreneurial allies. Desert executives have long been uncomfortable with the crackdowns on illegal immigration passed by Arizona legislators and carried out by Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio.

Policymakers overhauling American immigration reform have recently turned to a seemingly unlikely set of allies: business owners. Many executives have kept their labor costs down by employing illegal immigrants but directors are still showing themselves open to legislative change. “This is not a fight that’s going to be won in Washington,” one of New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg’s advisors explained, “It’s going to be won in districts across the country as representatives hear from local business owners, from local chambers of commerce, from job creators at home, all saying that passing immigration legislation is crucial to the success of their local economy.” Republican John McCain proclaimed “small business, large business, the chamber, the Business Roundtable, you name it, they’re all solidly” behind his proposed legislation. “We need them to weigh in on this issue,” he explained, “because we advertise ourselves as the party of business.” The senator had reason to have faith in his entrepreneurial allies. Desert executives have long been uncomfortable with the crackdowns on illegal immigration passed by Arizona legislators and carried out by Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio.

Some Beltway conservatives doubt business’s legislative influence. “I’ve heard from all sides on the immigration bill, certainly our Kansas Chamber of Commerce,” remarked Representative Lynn Jenkins, “But I will tell you, a majority of Kansans that I visit with are not as eager. And the power lies with the people, at least in Kansas.” South Carolina Representative Mick Mulvaney cautioned that CEOs “have come to the well so many times for their corporate welfare handouts that they have lost all credibility with the base of the Republican Party.” He predicted: “The days of the Chamber of Commerce being the gold standard may be coming to an end if they aren’t already in the past.”

That era began to unravel during the 1960s, then over civil rights for citizens (not immigrants). Top white Southern businessmen in particular found themselves struggling to maintain their carefully constructed racial moderation, which lay somewhere between the politics of liberal integrationists and reactionary segregationists. So-called “moderates” hardly earned their reputation as the South’s “best men.” Like their corporate contemporaries, these entrepreneurs, executives, and professionals were far more dedicated to free enterprise than equality. They had a gradual approach to reform, which frustrated civil rights activists demanding genuine justice, opportunity, and progress. Martin Luther King, Jr. went so far as to declare the “white moderate” the “great stumbling block” to freedom, a bigger obstacle than even “the White Citizen’s Councilor or the Ku Klux Klanner.”

This kind of moderation was worked out decades before the signing of the 1964 Civil Rights and 1965 Immigration Acts. For example, historian Kevin Kruse emphasized that Atlanta Chamber of Commerce members had long declared their city “too busy to hate” in an effort to attract outside investment. Yet they (like other urban boosters) hardly intended to upend Jim Crow. Delta promoters instead emphasized that the organization’s interwar "Atlanta spirit" factory-recruitment campaign fell within the Southern zeitgeist that provided transplanted manufacturers with a cheap, desperate workforce for their factories, warehouses, and homes. Even Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s 1941 executive order against discrimination in war production factories did not prompt Southern boosters to change this maxim. Elite Atlantans proved eager to have federal officials, military commanders, and Bell Aircraft Corporation executives build an assembly plant in nearby Marietta but raised nary an eyebrow at the contractor’s hiring policies, which were in flagrant violation of the president’s fiat.

A series of mid-1940s Supreme Court rulings against white-only primaries forced urban businessmen to explore managed integration. These decisions triggered registration drives in the urban South, most notably Atlanta, where activists tripled the number of black Fulton County registrants in just three weeks. This surge forced the white political and entrepreneurial elite to respond to these constituents’ demands, particularly the affluent and influential who had spearheaded the voting campaigns. Both Democratic candidates had to pursue African American votes during the 1949 mayoral race. Appeals included direct bids in newspapers and before civic groups as well as sit-downs with community leaders. William Hartsfield, the Chamber’s preferred candidate, won and subsequently brought minority elites into a biracial ruling coalition that extended city services into African American neighborhoods, forced the police chief to hire black officers to patrol these precincts, and ensured that white public officials would respectfully address African American constituents in all formal correspondence. But African Americans were still, for all intents and purposes, junior partners and second-class citizens in a brokered alliance replicated throughout the sprawling postwar South.

Race came to dominate the Atlanta Chamber’s suggestions for governing and expanding Atlanta sooner than in Western Sunbelt business organizations, like the Phoenix Chamber of Commerce. “I will give you one -- segregation. You can slice that one in two and have two,” a leading Atlantan curtly responded when asked about the two biggest issues facing the growing city in the 1950s. Leaders subsequently designated a postwar race relations committee to “develop [a] pattern for improved relations between the races.” A 1948 report on five years of Chamber activities crowed that members “coordinated local activities in interest of additional Negro parks. Supported expanded educational facilities for Negroes. Aided in planning new areas for Negro housing. Secured Negro policemen for Negro areas.” The region’s “best men” increasingly embraced such incremental desegregation of public spaces to avoid federal intrusions into local, state, and private affairs, to boost for outside investment, and to assure tourists that they would be visiting a thoroughly modern South. Yet these owners and managers still maintained discriminatory hiring practices, pay scales, and workspaces in their companies.

Delta entrepreneurs were among the first Sunbelt boosters to find themselves unable to please middle and working-class white reactionaries. Younger civil rights activists had no patience for free-enterprise moderation but so too the city’s white middling sorts. These lower-income residents felt the effects of racial moderation more so than municipal leaders because less-affluent whites depended on public transportation, recreation, and education, the public services Hartsfield and his contemporaries slowly desegregated. Frustrated suburbanites found a champion not in the Chamber of Commerce but in a greasy spoon popular with Georgia Tech students and area laborers. The Pickrick Restaurant’s owner Lester Maddox proved a Southern municipal renegade. He was as long on folksy charm, fury at elites, and dedication to individual rights as Sherriff Joe.

Maddox enjoyed tremendous support in his 1961 mayoral bid against Ivan Allen, Jr., the Chamber’s president. Economic progress through gradual desegregation and token integration defined Allen’s campaign, whereas Maddox assailed such policies as un-American. At issue, one of his ads read, “is whether we will return to sensible constitutional government BY and FOR YOU, the people, or if we will continue to compromise, surrender, and place ourselves under the control of those who would harm our families, destroy our property values, take our jobs, direct our businesses, tell us where to work, who to hire, where to live and what to think.” The Atlanta primary ended in a near tie. Allen did prevail in the later runoff with African Americans casting the votes that offset Maddox’s inroads among all segments of white Atlantans, including the city’s business elite.

Divisions between business owners and their customers have only increased since then. Gradualism played no small part in an Atlanta booster’s confident 1965 proclamation that the South had “become the Nation’s Economic Opportunity No. 1.” Economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman recently showed Atlanta’s fortunes to be as precarious as Detroit’s but the entire region actually remains the economic problem Franklin Roosevelt proclaimed it to be in 1938, despite the 1964 Civil Rights Act’s restrictions on discrimination. Wages are low across these states, where working conditions and workplace rights have declined for both native-born citizens and naturalized Americans (regardless of their racial or ethnic backgrounds). The landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act certainly did much to stop employment discrimination but it does little to oversee the casual, cashless transactions that define the nation’s millennial Craigslist economy, where illegal aliens compete for short-term work alongside legal residents and full citizens.

Executives have made little attempt to bridge the economic and political divides their predecessors created between workers and managers. McCain, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, and the Business Roundtable are all supporting the sort of incremental reform that will not challenge the free-enterprise conservatism behind the postwar South’s municipal race moderation. The current Senate bill does little to improve job prospects for anyone living or moving to any part of the United States, which scarcely makes this legislation’s business backers and populist opponents surprising.