1,892 Veterans Have Committed Suicide THIS Year?

"Volunteers in dark green hooded sweatshirts spread out across the National Mall on Thursday, planting 1,892 small American flags in the grass between the Washington Monument and the Capitol. Each flag represented a veteran who had committed suicide since Jan. 1, a figure that amounts to 22 deaths each day." New York Times March 28, 2014

The headlines and TV screens scream about the latest killing by an Iraq or Afghanistan veteran, like the army major who managed to murder nineteen others or the lowly soldier who recently killed himself and three others at Fort Hood. We keep asking ourselves Why, knowing we will either never really know or even if we come close to a truth, find it too hard to accept. The only time I ever asked Why was as a draftee in basic training in Fort Dix. A boy I barely knew who slept in the top bunk above me tried to hang himself, before someone mercifully cut him down. He was, one guy said, related to some big shot politician and we all assumed it must have had some connection.

In the recent shooting at Fort Hood the Times went all out, assigning thirteen. reporters to the story and ably covering every possible angle from Killeen, Texas, New York, Washington, Honolulu, Las Vegas, Guayanilla, Puerto Rico and St. Petersburg, Fla. It followed up with a probing article “War Pain Yields to New Anxiety at Fort Hood.” In the meantime, the government and the Pentagon sent 160 investigators and 80 FBI agents to interview, examine, probe and scrutinize every available human being in and around the vast army camp. If any serious conclusions are ever drawn no doubt it will avoid core issues about war and peace our political oligarchy will never accept.

I hope someone at the Times took time to visit their morgue and re-read Denise Grady’s superb 2006 piece of reportage, “Struggling Back From War’s Once-Deadly Wounds” where, rather early on, she wrote about what the two wars were doing to our soldiers and their families back home. In it, she wrote, “Survivors are coming home with grave injuries, often from roadside bombs, that will transform their lives; combinations of damaged brains and spinal cords, vision and hearing loss, disfigured faces, burns, amputations, mangled limbs, and psychological ills like depression and post-traumatic stress.” She came close to why bad things happened when the troops returned home. But back in 2006, few at home cared much. Just as when that inconsequential private in my barracks tried to hang himself, and a lifer sergeant later shrugged, telling our platoon, “People do crazy things. Mind your own business.”

Fort Hood, in Texas, said to be the largest army camp in the world, is named after Confederate General John Bell Hood, the southern “hero” who lost his arm and leg at Gettysburg and Chickamauga. Hood is close to Killeen, a city of 100,000, and a money-making machine because of its ideal location, selling food, goods of all sorts, housing, offering loans, some no doubt predatory to the soldiers and their families. It’s said to do even better economically that the state capital in Austin.

It is there that massive numbers of troops since 2003 have been collected and herded to and from the Middle Eastern war zones. In one sharp-eyed book, Making War at Fort Hood, author Kenneth T. MacLeish frankly admits that few of us “know as much as we think we do about what the violence done by and visited upon soldiers means for them or for us.” A 35-year-old Iraq veteran, married with kids, who joined up at age thirty-one so his kids would have health insurance and thinks he knows why vets return troubled, tells MacLeish the first time they talk about the war and its after-effects, “Don’t fuckin’ leave any of this shit out.”

Deep down we know why some men kill after they return home from war, even without those 160 investigators. Ann Jones’s They Were Soldiers: How The Wounded Return From America’s Wars: The Untold Story thinks she knows. Maybe. But she comes pretty close. To her, it’s the lack of connection between those who fought in a war no one understood while the rest of us were home “amusing ourselves to death” in Neil Postman’s marvelous phrase. Despite those ubiquitous “Support Our Troops” bumper stickers (someone must have made lots of money on them) our vets were regularly celebrated with self-righteous and bogus “Salute to Our Wounded Warrior” nights at baseball parks, the stands filled with cheering young non-veterans, never hinting that the war was based on a lie dreamed up by distant ideologues and supported, at least at the beginning, by a very large majority of Americans. Jones saw frightened soldiers in weird combat situations unlike that of Dad or Grandpa’s wars. It is a war, Jones believes, that never really ended while the American political establishment (now essentially non-vets) remains coiled ready to spring at our next enemy regardless of the price demanded from the “children of the poor and the patriotic.”

If you look even further try two scorching and imperative books for some genuine clues why some GIs kill. David Finkel’s Thank You For Your Service deals with the price tag our two wars it exacted in our latest experiment in regime change. Finkel talks about one of them.

“Two weeks before he killed himself, around the time of Aurora’s \

First birthday, he went to see his mother, who lives a tiny town in

Northern Iowa called Chester. ‘I’m not worth nothing. I’m not

worth nothing,” she remembers him saying.”

In Redeployment, Iraq vet Phil Klay put it this way. Looking back at Iraq’s terrifying and treacherous world he offers a contrast to USA/USA/USA: “Gluttonous fat, oversexed, over consuming, materialist home, where we’re too lazy to see our own faults,”—let alone understand why some came home and killed.

Is there any answer to Why? Israel has had many soldier suicides and Russia, another nation with a conscript army, must surely have had lots of suicides and killings. But Americans? Perhaps our volunteers have retained complicated forms of guilt, associated with death encounters—guilt because they survived and their buddies did not, guilt for having killed other human beings or perish the thought, come close. Guilt for having joined in or at least witnessed the destruction of people they never hated, guilt for having watched noncombatants suffer and die. There is always guilt in battle but it is particularly unbearable when few know why the battle is being fought.

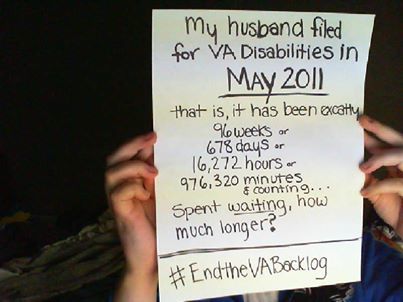

We have to wonder: How will we find the many billions and more it will take to care for these veterans for the rest of their lives? It’s a question that will no doubt remain unanswered and probably be forgotten as the decades pass, Iraqi and Afghan vets forgotten, and a new generation forced to fight and suffer in our inevitable wars to come.