Sanctions on Russia! (Or Not)

If the situation in the Ukraine deteriorates, what sanctions should the United States or the European Union impose on Russia next? Will the White House make it hard for Western investors and companies to do business in Russia, or Russian companies to do business in the West? For Russians to access Western capital markets, or for Russians to access their own funds offshore?

Sanctions are disruptive. They are most effective at the moment of implementation, when they shock an economic system. Over time, the shock wears off, a new equilibrium emerges and sanctions lose their bite. Sanctions are short-term measures, inadequate to counter the long-term challenge of Russian annexation of Crimea or of other parts of Ukraine.

And what of countries not party to the sanctions? We live in a multipolar world. Shall the US accept its sanctions are only partially effective? Or will the US confront countries not participating, forcing them to take a side?

Sanctions—and their big brothers, embargoes—have a checkered track record that should make us think twice.

Continental System

In the Napoleonic Wars both Britain and France used trade policy to advance military ends. Both set up embargoes and trade restrictions to prevent merchants from neutral states from trading with the other, but their embargoes and sanctions failed to bring down the other power.

Napoleon's Continental System reigned over much of Europe, from Spain and Italy to the North Sea. Along this coast, he forbade imports from Britain. Britain responded by forbidding—on pain of naval enforcement—ships from any country trading with France unless those ships first stop in the UK to be inspected. Napoleon in turn claimed that any ship submitting to such a search was to be considered British and seized.

Each side squeezed neutrals, but the embargoes did not wear down Britain or France. In enforcing trade restrictions both sides endangered their war efforts by risking expansion of the war in their own disfavor. In the 1790s British naval patrols inspired a league of armed neutrality—a combination of Scandinavia, Prussia, and Russia—in defiance of British searches of their ships. Britain went to war with Denmark twice and in 1812 with the United States over the enforcement of its embargo. These were pointless diversions which contributed nothing to the British effort to overthrow Bonaparte. France, too, irked neutrals, notably the U.S. with its trade policy, and invaded Russia—in part to extend the Continental System: a complete disaster. (The United States's own embargo, in 1808, of Britain and France, in retaliation for their embargoes was similarly daft, merely postponing, not avoiding, war.)

The U.S. will probably not go to war to enforce sanctions on Russia, which means that those sanctions will be ignored in China, India, the Middle East, and perhaps even the European Union. Deny Russia access to Western capital markets, and it may seek to funds from Chinese, Indian, Japanese, Saudi or other lenders. At best, sanctions will force U.S. policy makers to spend precious attention rallying reticent allies (such as the EU or Israel, which has declined to back the US stance on Crimea), to join a sanctions regime, which even if enforced, will not directly counter what is a military problem. The current deployment of Western troops in Eastern NATO countries, like Poland and the Baltics, is more apt.

Sanctions invite smuggling. Britain seized Heligoland in 1807, which became one of Britain's many offshore dodges. The islet in the North Sea, not far from the Elbe, the Weser, Denmark and the Netherlands—perfect for smugglers. Official British exports to Heligoland were soon over a £1 million a year1—to an island with hardly any permanent inhabitants. Once cargoes reached Heligoland, a merchant might bribe French officials in Hamburg to look the other way while he landed products with fake papers certifying their neutral origin. In neutral ports on the periphery of the Napoleon's empire, trade boomed even more readily. In Altona, a neutral Danish enclave abutting French-occupied Hamburg, goods landed freely. Altona residents could be buried in the Hamburg cemetery, and so sugar and coffee went across the Hamburg frontier hidden in coffins. French officials, suitably bribed, looked the other way. 10,000 people could cross the Hamburg-Altona frontier in an hour. One doubts every package, coffin and bag that went across was inspected. In what is now Croatia, enforcement of the Continental System was so ineffective that the French gave up even trying. Do we think that trade sanctions on Russia would fail to incite similar smuggling on Russian borders, particularly with members of its future Eurasian Economic Union?

Oil Crisis

The 1973 Oil Crisis is a modern example. Between October 1973 and January 1974, Arab OPEC countries cut oil production, quadrupling oil prices. But they did not stop the United States from getting oil.

Arab OPEC countries declared an embargo on the United States and the Netherlands. U.S. imports from Saudi Arabia, Algeria, Kuwait, Libya, and the United Arab Emirates dropped by a million barrels of crude and petroleum products a day between November 1973 and January 1974, a loss of 20% of US oil imports.

Arab oil was not sold directly to the U.S. But oil could be re-exported to the US from third parties; tanker routes and the oil majors distribution of oil were somewhat beyond embargoing countries' control. Arab oil reached the U.S. indirectly, and when it did not, it reached other consumers, allowing alternate suppliers to sell to the U.S.

The U.S. obtained much of its oil from neighbors. US Energy Information Administration figures show imports from Venezuela and Canada (by far the largest US suppliers) together sold a stable 40% of US oil imports throughout the crisis. Arab suppliers were not as large a direct source of oil. Together, the Bahamas, Virgin Islands, the Netherlands Antilles, and Trinidad and Tobago exported as much or more oil to the US as the Arab states had before, during or after the crisis. Nigeria, Indonesia and Iran, sold another 15% of US oil imports. (Iran was not party to the embargo.)

The absurdity of the embargo was on display in the Netherlands, a member of the European Community. The free flow of commodities between the Netherlands and its EC neighbors—the foundation of EC integration—made the Dutch part of the embargo a joke: oil could and did freely flow between the Netherlands and the rest of Western Europe.

What of gas shortages and lines at gas stations? These were consequences not of the embargo, but of production cuts. It was the cuts that mattered. If Arab OPEC states had imposed the embargo, but sold just as much oil as before, world oil supply would have been unaffected, and other oil suppliers would have rerouted to compensate.

Because they continued to sell oil during the production cuts, Arab states got rich off the oil crisis. They did so selling to Americans, which, on reflection, makes sense. Why raise prices and then refuse to gouge you biggest customer?

The Arab OPEC states grandstanded with the word “embargo.” Declaring one sounded good in Arab countries, and it gave Arab states the appearance of taking a stand against the US for it support of Israel in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War. It frightened publics and officials in many countries—who did not grasp how little control over the global flow of oil (as opposed to oil prices) OPEC had. Arab OPEC states threatened to withhold oil from Japan and other states unless they endorsed the Arab position on war. But Japan's and other countries' rhetorical support for the Arab cause did not translate into Israeli retreat on the ground. The embargo was mere talk. Arab production cuts were war profiteering.

Russia and Ukraine

Which brings us back to Russia. Russia's use of natural gas as an economic weapon damaging to Russia's economic interests, and eventually its political ones. Russia could use gas as a weapon again. And since its gas goes through pipelines, Russia has more control over where its gas goes than the Arabs had over their oil. But the gas weapon pushes European buyers away from Russian gas (they have been fleeing already because of Russia's use of the gas weapon against Ukraine). This lessens the gas weapon's efficacy in the future. Russia might be forced to sell to other markets, like China, where it may not command a high price, sacrificing both economic and political might.

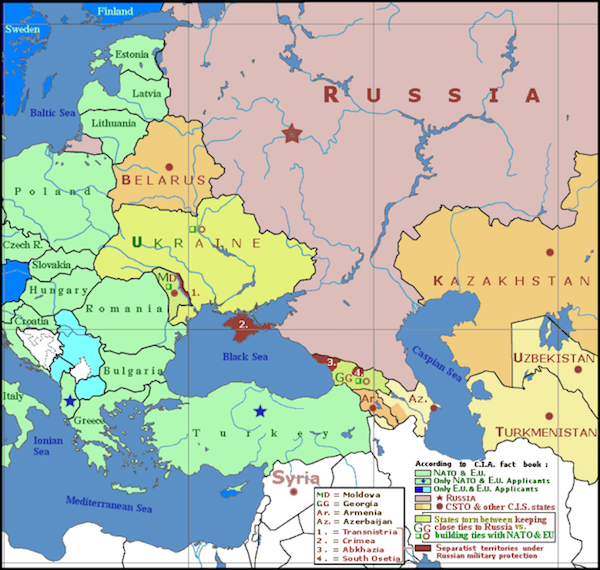

U.S. sanctions against Russia would be similarly self-defeating: forcing Russian trade toward the EU (if the EU does not support the US sanctions), and if the EU does impose sanctions on Russia, toward other China, India and other countries. What of Belarus (which has had its own resource feuds with Russia <http://digitaljournal.com/biz/business/russian-belarus-potash-cartel-may-resume-after-breakup/article/364798> and Kazakhstan, potential Russian intermediaries? Would they be sanctioned, too? Don't waste the time. Alliances, joint military exercises, and forward NATO deployment in Poland, the Baltics or Slovakia (which borders Ukraine) would be a more useful deterrent.

Embargoes rarely last. The Arabs wisely kept the 1973 crisis short. By 1974, oil producers were cheating, releasing extra crude to take advantage of the higher price. The embargo needed the production cuts to appear effective. Without cuts, the pointlessness of the embargo would be evident. And so Arab OPEC declared victory and went home.

Sanctions eventually force the other side to find other suppliers for gas, capital, and so on—for all fungible things. The US has had sanctions on Cuba for half a century. But Cuba trades today with Canada, Mexico, the EU and many US allies. Looking at the daily arrivals at Havana's José Martí International Airport: all those inbound flights from US-allied counties might make you forget Cuba's “isolation.” Russia is a much larger economy, when faced with sanctions, it will be that much harder to isolate.

Imposing sanctions can rally domestic audiences—they did in the Arab world, and they could in the US or Russia. Increasing sanctions could bring European allies toward accepting military reinforcement of eastern NATO states. But sanctions risk drawing the US into spats with Russia's neighbors, and major world economies, such as China, without which any sanctions on Russia are toothless. Such spats would distract from, not help, events in Ukraine. Sanctions don't stop bullets. Sanctions will not restore Crimea. They will not would not get Russia's crypto-soldiers out of eastern Ukraine. The Duke of Wellington did not win Waterloo with an embargo. The oil embargo didn't defeat Israel. Ukraine won't be won this way either.

___________

1British data give official not real values, which are best taken as a measure of volume, not value.