Why I Can't Let the Boko Haram Kidnappings Be Forgotten

A story in the Washington Post pondered what “might draw world attention to the outrage against humanity committed” in recentweeks. The New York Times editorialized that this outrage “cries to high heaven of man’s inhumanity to man.” Yet the world did nothing, causing the Times to condemn contemporary civilization’s insistence on traveling down the “dark byways of human hard-heartedness.”

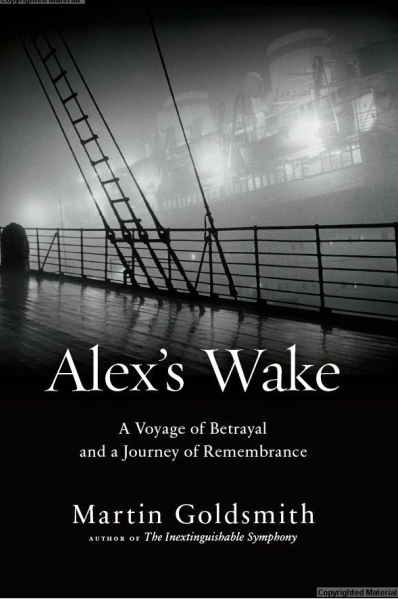

It was seventy-five years ago this spring, as a ship called the St. Louis carrying over 900 Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany was turned away first at its intended landing site of Havana, Cuba, and then denied entry at ports in the United States and Canada. The St. Louis, described by the Times as “the saddest ship afloat today,” bearing what the Post called its “pestiferous cargo” of stateless Jews, was forced to sail back to Europe. Though a deal was brokered to allow the passengers to disembark in either England, France, Belgium, or Holland, about 250 of them would be murdered in German concentration camps, among them my grandfather, Alex Goldschmidt, and my uncle, Klaus Helmut Goldschmidt.

Today the world has learned of another outrage against humanity: the forced abduction of more than 200 teenaged schoolgirls from dormitories in northeastern Nigeria, students kidnapped by a violent Islamic sect for the crime of seeking an education. The perpetrators call themselves Boko Haram, which in the local tribal language means “Western education is sin.” After reportedly murdering more than 2,000 people in the last four years, they have sexually assaulted these latest victims, sold them for about $12 each, and condemned them to a life described by a village elder as “a medieval kind of slavery.” “I’m crying now as community leader,” that man told the BBC, “to alert the world to what’s happening so that some pressure would be brought to bear on government to act and ensure the release of these girls.”

As the grandson and nephew of victims of global indifference, it is difficult for me to read about these atrocities in Africa without sorrow and a fierce desire to see something done to save those innocent girls. I was buoyed the other day to read the words of Senator Robert Menendez, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, who declared, “It is impossible to fathom that we might have actionable intelligence and we would not have the wherewithal -- whether by the Nigerians themselves or by other entities helping the Nigerians -- to be able to conduct a rescue mission.” Other countries, including England, France, China, and Israel, have offered assistance in the form of shared intelligence and satellite imagery, but nothing concrete has been forthcoming from the international community. Once again, it seems, the world is standing by as ignorance and brutality advance.

The Boko Harem kidnappings admittedly present a more complex set of issues than did the voyage of the St. Louis. Despite the dictates of the 1924 Immigration Law, it would have been comparatively easy for the Roosevelt Administration to allow the refugees to come ashore in Miami or Baltimore or New York. The Obama Administration, by contrast, would face a sizeable logistical and political task if it chose to mount, either on its own or with the assistance of other nations, the sort of “rescue mission” mentioned by Senator Menendez.

I’m generally opposed to military adventures abroad. I’m among the majority of Americans who welcomed our withdrawal from Iraq and look forward to the end of our involvement in Afghanistan. But I wish that, 75 years ago, the United States would have opened its “golden door” to my uncle and grandfather. Five years ago, Senator Herb Kohl declared that our indifference to the St. Louis affair “still haunts us as a nation.” I like to think that by now we as a nation have learned that there are moments in our history when we have to act as if we really believe that we are indeed our brothers’ and our sisters’ keeper. This is one of them.